A new class of super-strong porous materials that can selectively capture carbon dioxide and release it in response to a visible light trigger has been developed by researchers in the Netherlands, Italy and Poland. The work could have applications in carbon capture and could find uses in catalysis.

The work combines two recent innovations. One is in porous framework materials similar to metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), which were awarded the 2025 Nobel prize in chemistry, and closely related covalent–organic frameworks (COFs). These have been developed extensively for chemical separation, and a key target is to manipulate their switching properties in response to external stimuli to allow for the catch and release of molecules. Christopher Barrett of McGill University in Montreal, Canada says, ‘they do the job in the lab but I wouldn’t buy stock in equipping chimneys in factories with these … They’re like a little cube of sugar in your hands and you can crush them to dust,’ he says. The second development is in light-responsive functional groups. These have been added to framework materials before, but they have generally required UV light, which causes degradation of the scaffold.

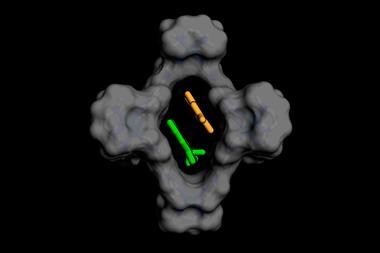

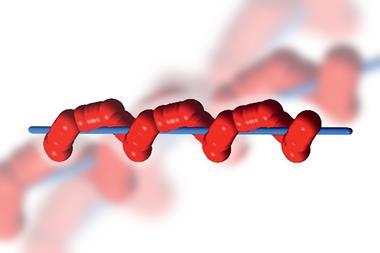

In the new work, Ben Feringa at the University of Groningen, who shared the 2016 chemistry Nobel prize for his work on molecular switches and machines, teamed up with experts on porous materials in Italy and Poland. They used 3D structures held together by rigid carbon–carbon bonds called porous aromatic frameworks (PAFs). ‘Porous aromatic frameworks are made using irreversible chemical reactions such as cross couplings, while in COFs it’s always a reversible bond that’s being used to construct the framework such as imine, which can hydrolyse,’ explains Wojciech Danowski at the University of Warsaw. ‘[PAFs] are almost impossible to destroy.’

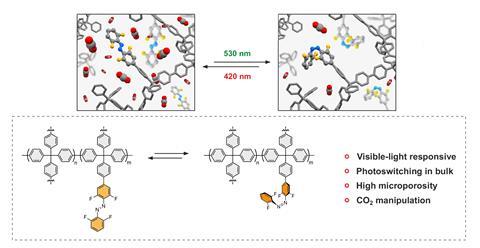

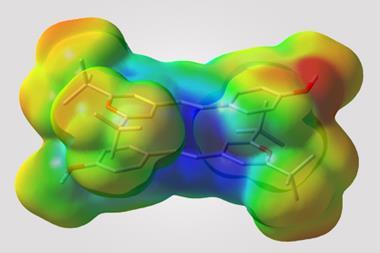

Some of the units were functionalised with pendant groups of the E isomer of o-fluoroazobenzene. The functionalised PAFs effectively and selectively captured carbon dioxide. Spectroscopic analysis showed that irradiation of the material with green light caused the pendant group to transform almost entirely to the Z isomer. In this state, the free volume of the structure adsorbed up to 14% less carbon dioxide. The researchers believe this is because the Z isomer reduces the free volume of the pore. Irradiation with blue light returned the pedant groups to the E isomer, restoring its carbon-capture capacity. Angiolina Comotti at the University of Milano-Bicocca, Italy, says that, following the ex-situ irradiation and comparison of the PAFs’ carbon dioxide uptake for the E and Z isomers separately, they are planning to follow the process in real-time, measuring how the adsorption changes while irradiating the material.

Barrett, who was not involved in the research, is impressed. ‘Ben Feringa has combined two separate advanced areas to solve a problem,’ he says. ‘People had tried to combine photoswitches with the weak stuff – the COFs and the MOFs … but there wasn’t enough room for the photoswitches to move and the structures fell apart.’ He explains that in the present material ‘the isomerisation happens all the way through so the CO2 can be breathed in and, with a light flash, breathed out. Brilliant!’

‘It’s definitely a significant paper,’ agrees Natalia Shustova at the University of South Carolina in the US. She believes that, beyond simple carbon capture, the paper could allow photochemical manipulation of reactions in a way that traditional porous materials, whose adsorption varies with temperature, do not. ‘With temperature, you cannot turn it off,’ she says. ‘How many hours is it going to take to cool down the material – I don’t know. Here you’re talking about seconds.’

Christopher Barrett’s affiliation was corrected on 19 February 2026

References

J Sheng et al, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2026, 123, e2520024123 (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2520024123)

No comments yet