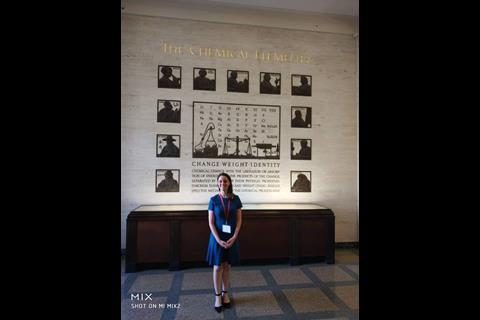

Zita Martins is an associate professor at Instituto Superior Técnico in Lisbon, Portugal

After completing her chemistry degree at Portugal’s Instituto Superior Técnico in 2002, Zita Martins was sure of two things. She wanted to pursue a career that combined her chemistry expertise with her interest in the universe. And to begin that career she would need to leave her home country. ‘I didn’t want to be just a chemist for the rest of my life. But there was no astrobiology in Portugal, as plain and simple as that,’ she says. ‘To work in this field, I had to leave home. My goal was to come back with all the knowledge and a network of contacts.’

Fast forward 18 years and Martins is back in Portugal, after stints in the UK, the US, the Netherlands and France, working primarily on space missions that aim to collect objects in outer space. Martins started working on space missions in 2007 by helping to develop methods for detecting organic molecules as part of an instrument for the ExoMars project, which she says gave her a ‘crash course on space missions’.

She’s now working on multiple projects, including the Japanese space agency’s Hayabusa2. This spacecraft delivered two rovers to the surface of an asteroid called Ryugu in 2014. The spacecraft also blasted a small crater in Ryugu, from which it collected samples. A capsule containing these samples landed in Australia at the beginning of December. This material will provide researchers with more evidence of which molecules exist on these primitive objects. ‘We know that the Earth was bombarded by comets, asteroids, meteorites and other planetary bodies about half a billion years after it was formed. This heavy bombardment delivered organic molecules to Earth. And then something happened that led to the origin of life. Something we don’t know yet. We want to see which organic molecules were delivered and may have played a key role in the origin of life on Earth. This is the ultimate goal – trying to understand how life originated on our planet.’

Earth is just one planet in the universe, yet chemistry happens all over the place

Hayabusa2 launched six years ago, yet space missions take much longer to conceive. Martins says it might take up to 20 years from submitting a proposal to blast-off. ‘You have to be extremely resilient. Nobody’s motivated for 20 years; we know how humans work. It’s challenging.’

‘When astrobiologists talk about organic molecules, I’m not saying DNA, RNA, nor proteins. We’re not expecting to find those complex molecules, but what we call simple molecules, like glycine or phosphorus. If that much.’ While these could be exciting findings, Martins stresses how crucial it is that the scientific community portrays any findings responsibly. She says she is always cautious when describing results, as are all of her astrobiology colleagues. ‘It’s a matter of ethics. You may extrapolate and give a hypothesis, but you can’t interpret your results as a certainty.’

Martins is also involved in the Comet Interceptor mission, which the European Space Agency is due to launch in 2029. This mission won’t bring samples back to Earth, but rather data from a comet that has never entered the inner solar system. ‘The comet’s chemistry remains very primitive, almost like the chemistry of the early solar system,’ Martins says. ‘It’s like a time travel machine.’

Besides analysing data and samples in her lab at Instituto Superior Técnico, in Lisbon, Martins teaches and manages a research group there. Working hard and meeting deadlines is essential, but she also encourages her team to celebrate large and even small victories together. ‘It’s really important, not only to achieve success but also to feel good as a group. I always want to be sure that people get along and that they are comfortable with each other.’

Barbie redefined

In 2015, Martins was appointed an Officer of the Order of Saint James of the Sword for exceptional and outstanding merits in science – one of Portugal’s highest honours. Then in 2018 she received a rather atypical prize for a scientist – a Barbie award for being one of the top 10 inspiring women to young girls in Portugal. As a young child, Martins never felt represented in Barbie toys because they never depicted her interests nor her aspirations. Now, she is proud to be a role model. ‘It’s massive to have a scientist like myself being recognised, a complete culture shift.’

With many missions on the cards, Martins has already achieved her personal one – bringing astrobiology to Portugal. Now, her objective is to grow local expertise and expand the field further, while showing others just how far-reaching chemistry can be. ‘Earth is just one planet in the universe, yet chemistry happens all over the place. So why not study that?’

No comments yet