For the first time, researchers have reported a new family of materials that maintains its conductivity in liquid, liquid crystal and solid states. Surprisingly, ions still swim swiftly across its crystalline structure with no decrease in speed. Such ‘state-independent’ ionic conductivity opens possibilities for safer solid-state batteries, as well as more efficient electronics.

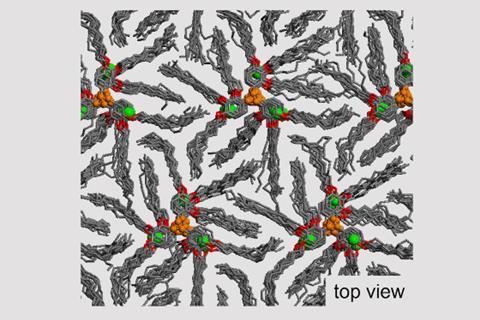

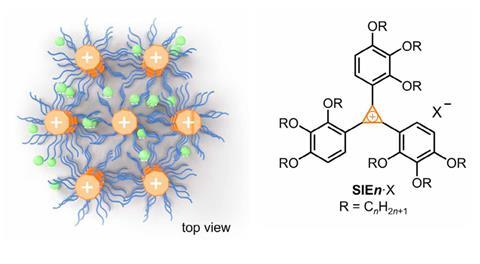

The discovery was serendipitous, according to lead author Paul McGonigal from the University of Oxford, UK. ‘We wanted to study how liquid crystals stack and create columns using structures with diffuse and symmetrical charge distributions,’ he explains. To create the new material, a rigid aromatic cyclopropenium cation at the core is combined with flexible hydrocarbon sidechains, ‘like a wheel with soft bristles’. This structure spreads the charge across the molecule, which allows ions to flow freely, even in the solid state. ‘The disorder in the dendritic structure ensures the ions easily hop around,’ says McGonigal.

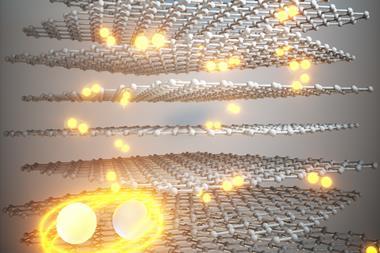

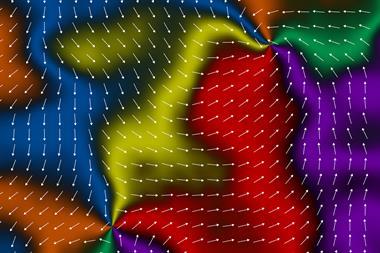

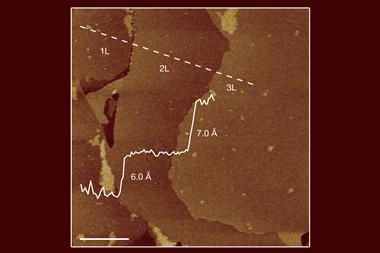

While the conductivity of the liquid crystal structure is comparable to compounds in the literature, it still stays strong in the solid state. ‘It’s a breakthrough to observe [this] across three states of matter – liquid, liquid crystal and crystal,’ says Amar Flood, an expert in self-assembly and supramolecular chemistry from the University of Indiana, US. Maybe most importantly, the mechanism is maintained too. ‘It’s remarkable, it appears to always occur in the same way,’ he adds. Indeed, the team ‘studied conductivity parallel and perpendicular to the liquid crystal assembly’, to help decipher the behaviour of ions in the solid state, which is isotropic – the movement is similar in all directions.

‘This study challenges the conventional expectation that conductivity comes from conformational freedom,’ explains Alberto Concellón, an expert in liquid crystals at the Institute of Nanoscience and Materials of Aragón in Spain. It is an unusual behaviour, he says, because ‘ionic conductivity in liquid crystals is generally … higher than in rigid solid electrolytes.’ However, researchers realise ‘the power of chemical design to control macroscopic properties … preserving liquid-like ion transport even in the solid state,’ adds Concellón. ‘It’s a delicate balance between weak ion pairing, self-assembly and residual flexibility in the solid state.’

McGonigal says it’s a start as, so far, the team only studied a small selection of sidechains, cationic cores and anions – chloride and bromide. Tweaking the structures could ‘start collapsing the columns’, he jokes, ‘but also potentially improve the properties after a first spectacular result.’

Concellón agrees it’s a great starting point: ‘the study establishes clear molecular design principles to inspire the development of related systems beyond a single class of molecules’.

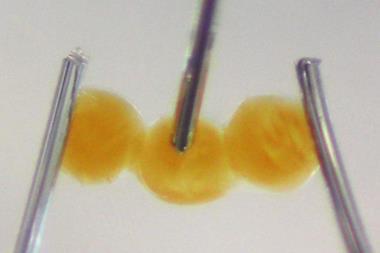

The importance of improving ionic conductivity in solids is key for applications in energy generation, storage and transportation, ‘where the electrolyte plays a central role in ionic mobility and device lifetime’, explains Concellón. In contrast to liquid electrolytes, ‘solids don’t leak’, says Flood, which increases the simplicity and safety of systems. Liquids in lithium-ion batteries, for example, are a common cause of accidents. But besides better batteries, the versatility of organic solids opens opportunities in flexible and efficient electronics. ‘We’re working with a group in Japan at the moment to implement our materials to modify the performance of memory devices,’ explains McGonigal. ‘Because it’s state independent, it’s easy to apply the electrolyte as a liquid to ensure a homogeneous coating, which keeps the conductivity once solidified,’ he adds. Now, the priority is improving the conductivity and versatility, as well as expanding the new family of materials with similar structures.

References

J Barclay et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.adk078

No comments yet