Commitment to gene and cell therapy treatments emphasised as unit broken up amid pharmaceutical division refocus

Pharmaceutical giant Novartis is disbanding its 400 person cell and gene therapies unit, even as it prepares to seek approval for a ‘breakthrough’ cancer treatment it is developing. Under the restructure, 300 people will redeploy to other parts of the company and a further 120 will be moved into other internal positions if available.

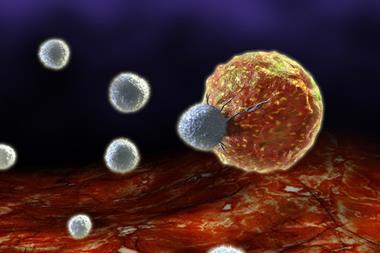

The unit has been home to Novartis’ chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy CTL019, which involves genetically modifying a patient’s own immune cells. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has designated CTL019 a ‘breakthrough’ for leukaemia treatments in children, accelerating the drug’s approval process. Novartis spokeswoman Julie Masow says that the firm still anticipates filing for approval with the FDA in early 2017 and in the EU later in 2017, while global clinical trials in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma continue.

Novartis announced in May that it would split its pharmaceuticals division into two business units, Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Novartis Oncology. ‘An isolated unit worked well under our prior pharma division structure,’ the company said in a statement. ‘But with a new integrated development model, we can efficiently advance our work on CAR-T as part of our focus in immuno-oncology by reintegrating the functions.’ Staff previously dedicated to cell and gene therapies will be ‘redeployed to share their knowledge and improve execution of novel therapeutics in the immunotherapy space’.

Yet the reorganisation may further jangle the nerves of staff that survive the reshuffle and investors worried about CAR-T’s prospects. This year Novartis presented data from a Phase I clinical trial of CTL109 involving 69 children showing high and durable complete response or remission in an impressive 93% of cases. However, 27% experienced cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a side-effect that can be severe and sometimes deadly, highlights Rachel Webster, senior director, oncology at the healthcare information firm Decision Resources Group.

‘When engineered CAR-T-cells are infused back into the patient they replicate to kill cancer cells,’ Webster underlines. ‘The immune system goes into overdrive. In doing so, the T-cells excrete large quantities of cytokines. CAR-T-cell therapy is likely a last resort treatment, but if that patient is going to survive the cancer, the therapy may have to nearly kill them first.’ Webster has identified this as one of CAR-T’s major challenges, constraining its commercial potential.

No comments yet