Cow pats from cattle fed tramadol could explain how the drug came to be in an African herb

In 2013 the surprising discovery was made that the opioid painkiller tramadol, thought to be synthetic, was being produced by the African herb Nauclea latifolia. However, new research casts doubt on this claim. Researchers from Germany and Cameroon conclude that the tramadol detected in the plants’ roots was actually the result of soil contamination by the urine and faeces of farmers and their animals. The team leader of the original study, however, is standing by his results.

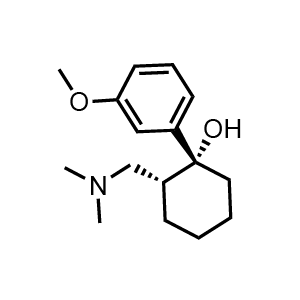

The flowering evergreen N. Latifolia grows widely in Cameroon and nearby parts of Africa, and is used by traditional healers to treat a wide variety of complaints including pain. In 2013, Michel De Waard of Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble and colleagues from elsewhere in France and Switzerland analysed the root’s chemical composition using spectroscopic analysis of methanolic extracts and found up to 0.4% +cis-2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol, also known as tramadol. Although several pharmaceuticals have been discovered in plants after being synthesised in the laboratory, this was the first time a drug had been found in clinically significant concentrations.

Analytical chemist Michael Spiteller of the Technical University of Dortmund in Germany and colleagues obtained a sample of the root with the highest concentration of the drug from De Waard’s group. Conducting their own analysis they found that, sure enough, it contained 0.4% tramadol. Spiteller’s group’s own samples, however, told a different story – none of them contained more than 0.00015% tramadol. Furthermore, samples from southern Cameroon contained no detectable tramadol at all. ‘I thought, “That’s strange – there must be something wrong”,’ says Spiteller.

Locals told the researchers that tramadol is readily and cheaply available from local markets or street sellers in northern Cameroon, and that farmers often consume far more than the recommended dose and feed it to their cattle. Taking tramadol helps the farmers to work all day in temperatures often exceeding 40ºC. This practice was not reported in the south. In such temperatures, farm animals often relax and excrete in the shade of trees, providing a potential route for high quantities of tramadol to get into plant roots. The researchers also detected both tramadol and several mammalian metabolites in surface, stream and well water and soil in the north of the country. Finally, they found trace quantities of both tramadol and its metabolites in the roots of other, unrelated plants like acacia in the same areas.

De Waard is unconvinced though. ‘We sampled this root in a national park where livestock is prohibited,’ he says. He suggests that baboons and other mammals in the national park that eat the fruits from the N. Latifolia trees, which may also contain tramadol, could explain the metabolites in the soil. He concludes: ‘This is a formal insult to the African populations and their traditional practices of using plants as medicines.’

No comments yet