Polymer that responds to multiple stimuli could bring shape-shifting plastics a step closer

Shape-shifting plastics which respond to external stimuli, similar to how Venus flytraps ensnare prey and touch-me-nots fold their leaves inwards when touched, have come a step closer thanks to a new polymer developed by US researchers. The work could lead to new classes of plastics with many applications including smart responsive coatings, sensors and controlled release vehicles.

Polymers have previously been made to reversibly change shape from triggers such as light and temperature. Now, Scott Phillips’ team at Pennsylvania State University, US, has broadened the scope by creating a polymer, Pcl2PA [poly(4,5-dichlorophthalaldehyde], that depolymerises from head to tail in response to multiple stimuli.

‘The field of head-to-tail depolymerisable polymers is really just emerging, with only a selection of polymers showing rapid and selective depolymerisation,’ says Phillips. ‘This depolymerisation response, however, is critical for enabling the multi-stimuli-responsive 3D materials in this work.’

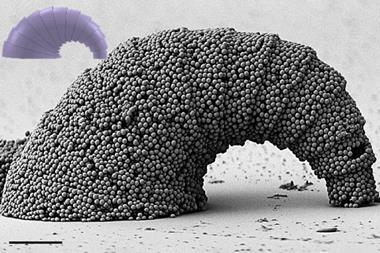

Previous research on the parent polymer poly(phthalaldehyde) (PPA) showed it to continuously depolymerise quickly in response to specific applied molecular signals.2 But its thermal instability and high sensitivity to mild acids and bases prevented manufacture of 3D materials using thermal-based manufacturing processes such as selective laser sintering (SLS), which fuses particles of the polymer together using a laser.

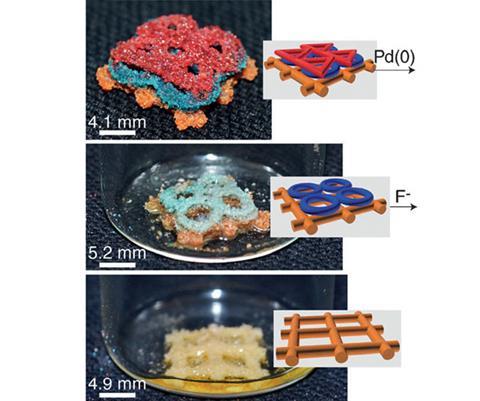

Improving the thermal stability of the Pcl2PA they synthesised allowed the team to make 3D objects with a simple SLS technique. They were able to create depolymerisable objects, including those that changed their shape and function in different ways in response to different chemical stimuli. The depolymerisation of the polymer works by end-capping the polymers with functionality – for example with tert-Butyldimethylsilyl ethers and allyl carbonates that respond to specific signals. Cleavage of the end-caps results in the polymer becoming thermodynamically unstable, leading to rapid depolymerisation to the monomer.

‘This may be important for specialty polymers which require the ability to depolymerise from one end of the chain in the presence of certain sensitising species, and it might be important in diblock copolymers or comb polymers where the end sequences can be readily removed,’ says Wayne Cook who investigates responsive polymers at Monash University, Australia.

But he also points out that selective polymer degradation and dissolution are already well known depolymerisation processes. ‘There are many polymers that can be printed using 3D technology and it would be fairly easy to print a structure with two polymers which were sensitive to dissolution or degradation in differing environments. Thus I think this paper has its main relevance in widening our ideas of how polymers can be selectively degraded, particularly by depolymerisation,’ Cook says.

No comments yet