Scientists manipulate microbial fuel production process with protein structure tweaks

Scientists in Germany have developed a highly targeted metabolic engineering technique to control the flow of electrons produced by the initial stages of photosynthesis in microalgae, and used it to increase hydrogen production by a factor of five.1

Hydrogen is increasingly being touted as an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional fossil fuels, but, ‘at present, hydrogen is mainly produced from natural gas, which makes it a “wolf in sheep’s clothing”,’ comments Oliver Inderwildi, a senior policy fellow at the Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, UK. Natural microalgae produce hydrogen by harnessing energy from sunlight, but their low production rate limits their practical application. Organisms typically use most of the electrons they generate to make the carbohydrates they need to live.

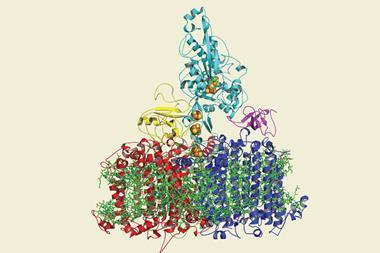

Previous studies in this area had focussed on curbing carbohydrate production.2 Now, Wolfgang Lubitz, of the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Energy Conversion, and co-workers have modified a ferredoxin protein responsible for distributing photo-generated electrons in the green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii with the aim of boosting its hydrogen output, whilst allowing the organism to be self-sustaining.

They identified two aspartic acid residues in the ferredoxin that interact with an enzyme that initiates carbohydrate production but not a hydrogenase that catalyses the reaction between two protons to form molecular hydrogen. Most residues in the ferredoxin will either interact with neither or both of these enzymes. By replacing these aspartic acid residues with alanine ones, binding of ferredoxin to the carbohydrate enzyme was supressed. Five times more hydrogen was produced was a result.

The group hoped for success but did not fully expect to find these residues, whose enzyme recognition role was not previously known. Lubitz attributes the discovery to the specificity of their technique: ‘This is a targeted experiment using a highly specific method, NMR, for [looking at] the interaction between these proteins.’ The team now plan to target other processes with their method: ‘There are many other partners which could lead to interesting applications if you use the same approach to find out about interactions … and even engineering other pathways.’

According to bioelectrocatalysis expert Shelley Minteer, of the University of Utah, US, this result boosts hopes for viable algal hydrogen production: ‘Until this work, algae just didn’t produce enough hydrogen to make it worthwhile. This improves fuel production and lays the foundation for future work to further improve hydrogen production.’

Collaborators at Ruhr-University Bochum, Germany, are currently performing further optimisations, with the ultimate goal of producing a commercially viable hydrogen producing organism.

References

- S Rumpel et al, Energy Environ. Sci., 2014, DOI: 10.1039/c4ee01444h (This paper is free to access until 1 October 2014)

- Y Sun et al, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 2013, 38, 16029 (DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2013.10.011)

No comments yet