Rising numbers of researchers and increased spending on science mask waning commitment to research among richer nations

The number of people working in research around the world has grown by 21% between 2007 and 2013 to 7.8 million, according to the Unesco Science Report, which tracks trends in science, technology and innovation around the world. And these people are moving around more than ever before to study and work.

The report finds that the EU has the most researchers, with a 22% of the global total. Since 2011, China (19%) has overtaken the US (17%), while Japan’s share has shrunk from 11% (2007) to 9% (2013) and the Russian Federation’s share from 7% to 6%. These five regions still account for 72% of all researchers.

The increasing mobility of these researchers is perhaps one of the most important trends of recent times, says Luc Soete of Maastricht University, lead author of the report’s executive summary. Students from Arab states, central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and western Europe are most likely to study abroad. Europe and North America are still the preferred destinations. The US alone receives 49% of international students enrolled in doctoral science or engineering courses followed by the UK (9%), France (7%) and Australia (5%).

The figures show an international labour market where competition is increasing dramatically, says Soete. ‘However, the market is completely one-directional so it creates tremendous pressures on attractive destination countries such as the US and the UK, while there is a shortage of people finding positions in Africa. China is becoming more attractive as its research system catches up.’

Jonathan Adams, chief scientist at technology company Digital Science, says the key point on PhDs and postdocs is that there have been far too many to fill academic openings for some decades. ‘The problem is that most supervisors are not honest enough with their acolytes about their long-term career prospects, which is why we get periodic dismay [about employment prospects].’

Gender gap

However, less than one-third of researchers are women, but a growing number of countries are backing policies to correct this imbalance. Female researchers presently have more limited access to funding than men, are less well represented at prestigious universities and remain a minority in senior positions. The greatest shares of female researchers are not always to be found in the most developed regions: for example, 44% of researchers in Latin America and the Caribbean are women and 37% in the Arab states, compared with 33% in the EU. South-east Europe has the best gender balance of any region with half of researchers female.

The findings are not encouraging for the pipeline for women entering research, comments Dorothy Griffiths, provost’s envoy for gender equality, Imperial College London. ‘While women have more or less achieved parity at the junior levels (bachelors and masters) and are closing the gap at the PhD level (43%), it is very disappointing to see a big gap remain in the move from PhD to researcher (28%).’ The global variations are ‘strong evidence of a cultural problem, lying in the education systems and attitudes within science. Globally, we are a long way from equality’.

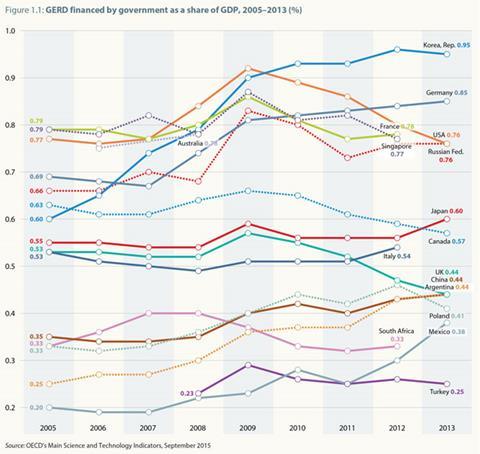

A growing research community has been possible because investment in R&D has remained buoyant despite the economic crisis of 2008. R&D expenditure rose by 31% between 2007 and 2013, more than global GDP that only rose 20%. However, the report notes that wealthier countries have cut back on research spending as part of a wider austerity drive over the past five years. This trend is particularly apparent in Canada and Australia, where significant cuts were made to research funding, and applied sciences were prioritised over basic research. Increases in R&D spending in countries, such as Italy, the UK and France, owe a great deal to the private sector, which has compensated for frozen or falling public spending.

Committed to research

By contrast, lower income countries have stepped up their public commitments. ‘Most emerging countries are in no doubt that research and innovation are important for future growth, and that goes for the general population and the policymakers,’ says Soete. Kenya, for example, devoted 0.79% of its GDP to R&D in 2010 compared to just 0.36% in 2007. R&D spending is also increasing in Ethiopia, Ghana, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique and Uganda. However, he adds that ‘it will be interesting to see in future if emerging countries, such as Brazil, which is in deep trouble at the moment, will continue to commit the same levels of investment, or even China, where the economy is slowing down.’

Overall, the US remains at the top of the league table, accounting for 28% of global investment, followed by China (20%) which has now overtaken the EU (19%) and Japan (10%). The rest of the world, while representing 67% of the global population, accounts for just 23% of global R&D investment. Nevertheless, research investment by rapidly growing economies such as Brazil, India and Turkey is increasing fast, the report adds.

These reports are based on official government statistics so should be taken with a pinch of salt, warns Kieron Flanagan, a science and technology policy researcher at the University of Manchester in the UK, but adds that the broad trends seem right. Science is certainly becoming more global with more countries joining the ‘club’, he says, and the richer countries’ share of global spend is starting to shrink. However, he adds: ‘It is contradictory that while science is getting more global, more diverse and more connected, funding and management remain nationalised, which can erect barriers to mobility.’

No comments yet