Head of British Academy recommends more flexibility for the Research Excellence Framework to end ‘gaming’ of the exercise

A review of the UK’s research excellence framework (REF) makes recommendations to cut its costly price tag and rein in distortions to the research system. The REF guides the annual distribution of £2 billion in research funding across the university system meaning it has a huge impact on how the community organises itself.

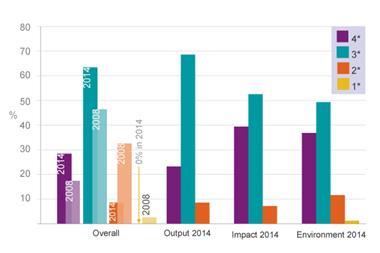

The review by Lord Stern – president of the British Academy – flags concerns over the cost of the research assessment, which ballooned from an estimated £66 million in 2008 to £246 million in 2014. It also identified gaming of the system, such as last-minute hirings to boost an institute’s score. REF can also drive researchers towards safe topics and short termism, Stern notes.

In all, the review makes 12 recommendations. Arguably the most radical is the inclusion of all active research staff in REF, which should simplify management and cut incentives to game the exercise. Exclusion from REF can affect career choice, progression and morale.

The review comes hot on the heels of the government’s white paper on improving higher education and a review of the research councils.

‘If you take the game playing out the cost falls,’ says Richard Winpenny, head of the school of chemistry at the University of Manchester, UK. He notes that most universities essentially ran a mock REF exercise every year or every other year, looking to see who was on track for REF 2014. ‘It demotivated staff and led to extreme short termism.’

‘A lot of the work was in choosing which researchers to include, but that’s also the area of most gaming, with some universities putting fewer people forward to push their grade average up,’ adds James Wilsdon, research policy expert at the University of Sheffield, UK.

Robert Parker, chief executive of the Royal Society of Chemistry, welcomed the results of the review. ‘The continued focus on peer review with selective metrics being made available as additional guidance for discussions is appropriate.’ He supports broadening the definition of impact and welcomes the ‘recommendation to reward the impact of interdisciplinary and collaborative research directly’.

More flexibility

Stern recommends flexibility for faculty to tune the amount of research they submit for the exercise. ‘That seems to me eminently sensible, because if someone is indulging in a long-term, high risk policy, they might be only able to produce one paper every few years,’ Winpenny says.

And the report argues for greater emphasis on a body of work from units or institutions rather than narrowly focusing on individuals, with impact case studies widened to include influence on public engagement, culture and teaching, as well as policy and applications more generally. It could ‘move universities from a business model that is stated as being to do research and educate, to research–education–impact,’ says Richard Templer, director of innovation at the Grantham Institute, Imperial College London, UK, who suggest REFs could be carried out just once a decade.

So influential is REF, that universities became driven by a process that is supposed to assess research, not guide it, Winpenny says. As part of a 2008 chemistry assessment, Templer observed the downsides of gaming: ‘This has had longer term damaging effects to the department concerned as star academics play one off against another and raise the stakes so high that the costs impact adversely both on university economics and, more importantly, on departmental morale.’

Late hiring before REF, including contracts that give a subsidiary post for researchers abroad, is another form of gaming; outputs should be submitted only by the institution where the work was carried out, Stern recommends. He also advises that peer review remains central, with metrics provided to assist panel members.

End gaming arms race

‘Stern gives us a framework to reduce the gaming and burden of the exercise,’ says Wilsdon. ‘But a lot now rests with the sector. We need to call time on the arms race of gaming that has accompanied research assessments in recent years and incorporate these recommendations.’ He saw concerns on social media from early career researchers, but says a lot stems from a misunderstanding. ‘Stern aims to take the burden off individuals and put it where it belongs – on managers.’

The review advises the governments and funding councils to act fast and issue a formal consultation to the community by the end of this year, with decisions published in summer 2017. This would give universities time to prepare for submissions to be collected in 2020, with assessment in 2021.

‘This [consultation period] seems six months longer than they need. These rules make more sense than the previous set of rules, so let’s get on with it,’ says Winpenny. ‘[Until then] universities will be making plans and preparations to play two distinct games.’ Wilsdon agrees: ‘The sooner rules can be nailed down the better.’

But the whole review needs to be read properly, Winpenny warns. ‘These are cohesive recommendations; this is not a pick and mix. You take the lot and it makes a great deal of sense.’

No comments yet