By making 340,000 measurements of the strontium isotope ratios along a woolly mammoth’s tusk, researchers could track the animal’s movements throughout its 28-year life.

Most populations of woolly mammoth disappeared as part of a mass megafauna extinction around 12,000 years ago, although the last remaining populations died out only around 4,500 years ago. Fossils provide direct evidence only for where an animal died: little is known about woolly mammoths’ movements while they lived.

Researchers in the US and Canada have now studied a single, 17,000 year-old tusk from a male woolly mammoth held at the University of Alaska museum. Like those of modern elephants, mammoths’ tusks grew throughout their lives, incorporating minerals from food. Mammoths obtained strontium from plants, whose strontium isotope ratio (87Sr to 86Sr) depends on where they grow.

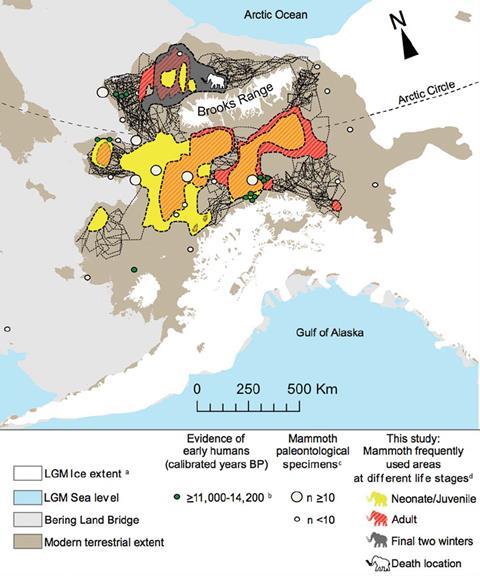

The analysis revealed that for the first two years of its life, the mammoth mostly occupied a single river basin in Alaska. The animal then roamed widely, covering enough ground almost to circle the Earth twice. In its last 1.5 years, it confined itself to one region just inside the Arctic circle, where the fossil was found.

Analysis of the ivory’s nitrogen and carbon isotope ratios also showed that, towards the end of its life, the mammoth was depending on its own protein and fat reserves – it probably starved to death.

References

M J Wooller et al, Science, 2021, 373, 806 (DOI: 10.1126/science.abg1134)

No comments yet