Report calls for joined-up approach that brings together charities, industry and universities

A report on the state of drug discovery in the UK has said that failure rates are too high, and called for sweeping changes to the current bench-to-bedside model. It said there needed to be a more joined-up approach among industry, academia and public bodies such as the NHS that can ensure access to patient data, as well as and new ‘humanised’ technologies for identifying targets.

The State of the discovery nation 2018 report was produced by the UK’s Medicines Discovery Catapult together with the Bioindustry Association and Innovate UK. It combined existing research with interviews with company leaders to identify the main challenges for UK drug discovery, with a focus on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

The report points out that failure rates in the existing discovery landscape are rising, with the number of drugs launched per billion dollars spent falling nearly thirtyfold over the last four decades, and says that drastic changes are needed if the UK’s R&D community is to reverse this ‘productivity paradox’.

‘We see the market segmenting from the blockbuster products of old to a more directed, targeted and precise medicines future,’ says the Medicines Discovery Catapult’s chief executive Chris Molloy. ‘And that requires the model to break and change.’

This will likely involve a shift from the left-to-right approach for drug discovery – starting with a publication and ending up with a product – to one that is ‘circular’, using data from patients to inform target choice. The aim of this is to make the early stages of research more predictive of how a drug will work.

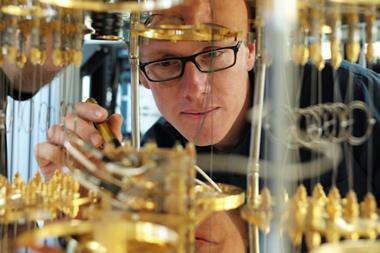

At its lab at Alderley Park in Cheshire, the Catapult is developing more ‘humanised’ assays involving human stem cells or organoids as a step towards this. It is also supporting the development of stratified early-stage clinical trials involving more specific groups of patients.

The report also indicated that even when useful patient data does exist, most SMEs struggle to access it, as well as human tissue samples. To tackle this, the Catapult wants act as a broker between SMEs and larger organisations to share information and resources that could smooth the discovery process.

‘We have a huge opportunity with the NHS and other organisations who have consented patient data and patient samples,’ says Molloy. ‘As highly fragmented, small organisations, SMEs find it challenging to work with these large national stakeholders. The Catapult is a valuable bridge between those two worlds.’

He adds that there is a general need for more collaboration. ‘Not just the legacy collaborations between a large pharma company and an academic organisation, for example, but between multiple SMEs, SMEs and technologists, SMEs and academics, and – very importantly – between SMEs and research charities.’

The Catapult has already begun to develop a portfolio of drug discovery programmes that focus on specific disease areas, each supported by a research charity, such as Antibiotic Disease UK, which are linking with companies looking to tackle antimicrobial resistance. ‘We believe that these flexible but important collaborative consortia will be the future model of drug discovery and early development,’ says Molloy. Taken together, he adds, the report’s findings outline a plan that will help the UK ‘play to its strengths’ when it comes to developing new medicines.

‘A view of discovery which starts with the patient, identifying very specific patient needs, will lead us to a future where you might have smaller patient populations […] but better health outcomes,’ Molloy concludes. ‘And those will drive better value.’

No comments yet