The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has issued stricter safety standards for four different per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water, saying that these chemicals are more hazardous than previously thought. Now the agency is considering regulating these compounds as one class rather than individually.

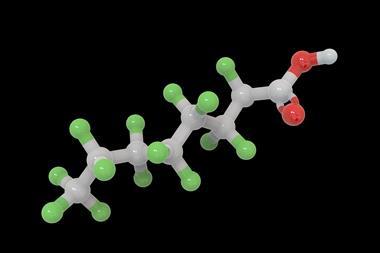

So far, the EPA has identified about 8000 different types of PFAS compounds. This family of highly-fluorinated chemicals, which have been in use since the 1940s in various industries, share attractive properties such as the ability to repel oil, grease and water, and can be used as lubricants.

The EPA’s new health advisories, announced on 15 June, will adjust exposure levels for the two most well-known and best-studied of these compounds in drinking water from 70 parts per trillion (ppt), set in 2016, to 0.004ppt for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and 0.020ppt for perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS).

While environmental groups like the Natural Resources Defense Council applauded the EPA’s actions, the American Chemistry Council (ACC) – the trade association for US chemical companies – said the agency’s process for developing these new lifetime health advisories was ‘fundamentally flawed’.

The EPA based its revised standards for PFOA and PFOS on toxicity assessments that are currently being reviewed by the EPA’s science advisory board, according to the ACC. ‘Rather than wait for the outcome of this peer review, EPA has announced new advisories that are 3000 to 17,000 times lower than those released by the Obama administration in 2016,’ the organisation said. ‘These new levels cannot be achieved with existing treatment technology and, in fact, are below levels that can be reliably detected using existing EPA methods.’

In addition, for the first time ever, two other PFAS chemicals – hexafluoropropylene oxide (HFPO) dimer acid and its ammonium salt, known by the trade name GenX, and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) – will be subject to federal health advisories at 10ppt and 2000ppt, respectively. GenX chemicals are considered a replacement for PFOA, and PFBS an alternative to PFOS.

Both PFOA and PFOS have been shown to harm human health and were phased out years ago, yet they remain ubiquitous and can be found in human urine, breast milk and umbilical cord blood. Studies have linked these two compounds to problems like liver damage, thyroid disease, and birth defects and fertility problems.

Change in the science

‘The updated advisory levels, which are based on new science and consider lifetime exposure, indicate that some negative health effects may occur with concentrations of PFOA or PFOS in water that are near zero,’ the EPA said. Based on the new data and its draft analyses, the agency stated that the levels at which negative health effects could occur from PFOA and PFOS exposure ‘are much lower than previously understood’ when EPA issued the 2016 health advisories.

These new lifetime health advisories are not enforceable, but the agency has plans to propose the first-ever US federal drinking water regulations for PFAS by the end of the year.

Beyond issuing these new PFAS water restrictions, the EPA also announced that it will make available $1 billion (£829 million) to states to help them address PFAS and other emerging contaminants in drinking water, through interventions like water quality testing and installation of centralised treatment technologies or systems.

The EPA acknowledges that these new health advisory levels for PFOA and PFOS are below the amounts that current analytical methods can measure. While these interim health advisory levels are subject to change since the advisory board is reviewing its analyses, the agency does not anticipate any changes that are greater than the minimum reporting levels.

Meanwhile, the EU is ahead of the US when it comes to regulating PFAS. In September 2020, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) set a new safety threshold for the four most common PFAS, including PFOA and PFOS. That threshold is a group tolerable weekly intake of 4.4 nanograms per kilogram of body weight per week.

No comments yet