The Eurasian woodcock’s white tail feathers reflect nearly a third more light than any other feather, research led by Imperial College London has found.

Scolopax rusticola are primarily brown, but they do have patches of white feathers beneath their tails that are can be seen when their tail is raised and also during courtship display flights.

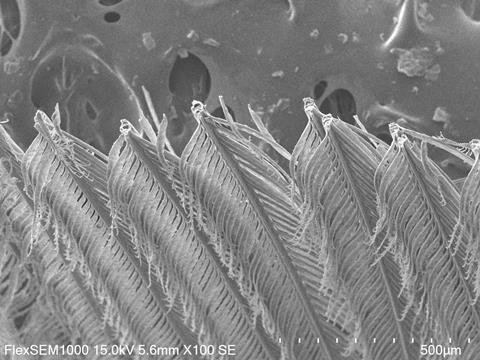

The researchers used electron microscopy to image feather structure, spectrophotometry to measure reflectance and models to characterise how photons interact with structures inside the feather. Unexpectedly, the team found that these feathers reflected up to 55% of light – 30% more light than any of the feathers whose diffuse reflectance was previously studied.

Lead author Jamie Dunning, an evolutionary ecology PhD candidate at Imperial, says that the mechanism at work here is similar to structural colour, except that a single colour isn’t being reflected, but rather a broader spectral reflectance.

Structural colour arises from the reflection of light from microstructures and nanostructures, rather than chemical pigments, he explains. For example, reds, oranges and yellows are typically pigments produced by the bird, whereas blues and iridescent plumages are usually created by complex nanostructures. Those systems interact with light hitting the feather, absorbing and reflecting certain parts of the wavelength.

‘What we have described are structures (not chemicals) that are reflecting light back across wavelengths,’ Dunning explains. ‘The microstructures we have described, as well as the internal nanostructures, are maximising the wavelength across that spectrum.’

References

J Dunning et al, J. R. Soc. Interface, 2023, DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2022.0920

No comments yet