From iridescent butterflies and beetles to fish-scales and petals – can nature show us how to make sustainable pigments and dyes? Angeli Mehta takes a look

The vibrant colours of the natural world are produced in different ways: inherently coloured molecules that absorb light or compounds that luminesce. But a stunning array of deep and long-lasting colours are achieved by mechanisms which are themselves colourless. Known as structural colour, it arises through the reflection of light from complex nanostructures found in the feathers of birds, the fruits of some plants or the hard outer shell of beetles. These multi-layered structures produce iridescence, whereby the colour appears to change depending on the angle of view, whereas chemical pigments produce colour that looks the same from all angles. Both pigment and structure are often used together to enhance colour: last year, for example, Dutch researchers showed that the glossy yellow of the buttercup is achieved both through a yellow carotenoid pigment and a thin film structure.1

Different species use different materials and structures, and the role of structural colour can have completely different functions in different organisms or perhaps none (that we currently understand) – as is the case in some bacteria. Structural colours have evolved to attract pollinators or mates, to provide camouflage or even to signal danger.

Isaac Newton described structural colour more than 300 years ago but it’s only recently that chemists, material scientists and physicists have turned their attention to the challenges of understanding and recreating it.

Each vehicle has over 300 billion pigment flakes acting like tiny mirrors to produce the vivid blue

Labs around the world are working on different techniques to understand and mimic the geometry of light-scattering and reflective natural materials. They hope to make sustainable pigments out of non-toxic compounds that won’t damage the environment, or reflective coatings to keep interiors cool. Paint manufacturer AkzoNobel has been working in the UK with the Natural History Museum in London and researchers at the University of Sheffield to identify which animals and plants have vivid whites and blues, and then to discover the structures which underlie those colours. Its aim is to try to mimic those in the lab and ultimately the paint-pot.

Researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, US, are starting to work with commercial partners on a polymer coating for windows that reflects back infrared energy, while allowing visible light to pass through. This would reduce the need for air conditioning in warm climates, so cutting the energy bills and carbon dioxide emissions associated with it. The idea is to produce a low-cost DIY coating that, with wide adoption in the US, could cut carbon dioxide emissions by up to 24 billion kilograms a year – the equivalent of taking 5 million cars off the road.

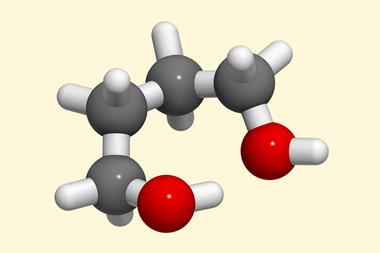

The inspiration came from a discovery that certain block copolymers, shaped like a bottlebrush, self-assemble into nanostructures that reflect light at different frequencies. Project lead Raymond Weitekamp explains that the ‘polymers are mostly composed of everyday plastics such as polystyrene and polylactide, but the chains are stitched together in a very specific arrangement which enables them to self-assemble into nanomaterials with structural colour’. Since the discovery, Weitekamp and his colleagues have been investigating these materials as less toxic alternatives to dyes and pigments in use today.

Blue: a tough task

Scientists at Toyota’s research labs in the US and Japan spent 15 years working out how to recreate the vivid, iridescent blue of the morpho butterfly’s wings. The layered scale structure of its wings strongly reflects a narrow wavelength of blue light that can be seen from afar.

‘Toyota Japan had developed structural layers but the process was expensive and some focused on a rainbow colour changing with viewing angle – instead we want solid colour whatever the angle. This is very hard to achieve,’ explains Mindy Zhang, general manager of Toyota’s US research labs. A colleague did some simulations that suggested the goal was achievable, ‘then we started to think about how to realise it’.

The nanostructure used in the morpho butterfly scales has been described as like a fir tree. One of the physicists experimented with pairing up materials that in a multi-layered format would reflect the same wavelength of light from all angles. He eventually chose titanium and hafnium oxides but there was a drawback: 31 layers were needed, making it impractical. Working with US pigment specialist Viavi Solutions, the researchers eventually managed to reduce the number of pigment layers to seven, with the addition of aluminium to boost reflectivity. Once they’d made the new pigment, it took a further year to ensure it could be dispersed in a water-based paint, in an automotive paint system. It takes eight months to produce enough pigment for 300 vehicles; each vehicle will have over 300 billion pigment flakes that each act like tiny mirrors to produce the vivid blue.

While Toyota has now worked out how to produce a wide spectrum of colours, ‘we’re still thinking about the layer design. The materials might change further,’ suggests Zhang.

Nature’s polymers

Nature has done it much more efficiently. In fact, some plants can make both solid and iridescent colours from one of earth’s most abundant polymers – cellulose.

Silvia Vignolini is in the department of chemistry at the University of Cambridge in the UK and has been exploring how plants use cellulose to make nanostructures. She first got interested when looking at the intense blue of the fruits of an African plant – Pollia condensata or marble berry – which maintain their colour for decades. A specimen at the UK’s Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew is still bright more than 150 years after it was picked in Kenya, while the chlorophyll pigment in the leaves of the plant faded long ago.

Scanning electron microscopy of the berry revealed cellulose nanofibrils, which were arranged in beautiful helical structures, twisting right and left, so they circularly polarise light in either one direction or the other to produce what artists would describe as a ‘pointillist’ effect. Vignolini and her team wondered if they could design a similar optical appearance with the same polymers. ‘If we can use cellulose – especially from food or agricultural waste – then we can obtain sustainable and non-toxic pigments.’ But the task is not straightforward, she adds, and much research remains to be done.

Vignolini’s lab has been using a very pure source of cellulose from cotton linters – the short fibres left on cotton seeds after the longer fibres are removed to make textiles. The fibres are themselves made up of bundles of nanofibrils. Hydrolysing the cellulose fibres with sulfuric acid delivers rod-like nanocrystals. Suspended in water, they self-assemble into structures that resemble flattened spirals. As the water evaporates, the concentration of the nanocrystals increases and the colour appears. The structures can be squeezed to make a thin film with uniform colour and adding a surfactant makes the film less brittle and more flexible. Vignolini’s group is trying to play with the optical appearance of the film: controlling the length and alignment of the nanocrystal rods influences the colour reflected by the helicoidal structure. The appearance of the colour can also be altered using a magnetic field.

‘If you want to coat a large area, it’s difficult to do it with a film, so again we asked how does nature do it?’ Vignolini’s team used microfluidics to carefully control the size of the droplets to create cellulose nanospheres of the order of 10-50µm. To scale up, however, they have used emulsion methods to disperse the microspheres.

Grinding the resulting cellulose nanocrystal films into flakes of varying sizes means it’s possible to produce powder for applications as diverse as food colourings and paint. Making a water-soluble paint is ‘really difficult’, however, because the cellulose is hygroscopic and attracts moisture, so the nanocrystals get damaged. Vignolini says her team does have some ideas of how to get around the problem.

Whiter shade of pale

‘We started work on colour first, then moved to white: making white is a lot easier,’ says Vignolini. Now it’s a question of how to manufacture the films on a kilogram scale in a cost-effective manner. The challenge is to create white in as thin a layer as possible. ‘An analogy is to have to apply multiple coats of white paint to cover a red wall – but you’d like to do it with just one coat of paint. That is the challenge.’

There are potentially good quality sources of cellulose – mango or orange peel, for example – that could be useful in a smaller scale and sustainable set up. But one major untapped resource is wood pulp. Researchers at the University of Aalto in Finland are looking for ways to revitalise the country’s forest products sector, as newspaper closures have meant a steep decline in demand for paper. Not only is cellulose a well-understood and sustainable material, but there is a ready-made industrial infrastructure. Now Vignolini is working with the Finnish scientists on a technique to develop ‘a really good intensity of white’.

She is seeing an interest from a range of industries, from pigment makers to cosmetics, all searching for alternatives to whitening agents like titanium dioxide. Last year the European Chemicals Agency classified it as a potential carcinogen if inhaled. This has led cosmetics firms to seek alternatives and Vignolini’s group is now working with French group L’Oreal as part of its sustainability agenda. One goal is to replace the titanium dioxide it uses in lipsticks, and potentially other pigments in both lipsticks and hair-colouring.

Hendrik Hoelscher at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany has also been working on potential alternatives to titanium dioxide, and this time the inspiration comes from the chitin scales of the white beetle, Cyphochilus insulanus.

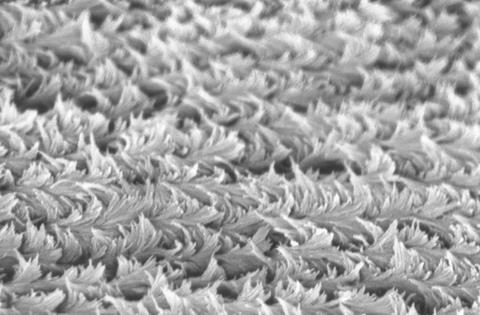

Most beetles, Hoelscher explains, produce extremely good scattering of light – by nanobubbles inside their scales. ‘Looking at them under an electron microscope, you see very small irregular or random structures like foam. Because the bubbles are so small, the light is scattered efficiently.’ White beetles, he adds, ‘achieve fabulous whiteness with very thin layers’.

Hoelscher’s lab has tried two techniques to recreate the light scattering structure. One used supercritical carbon dioxide to dissolve a polycarbonate at high pressure.2 Decreasing the pressure means the carbon dioxide returns to a gas and forms bubbles in the polymer – which then appears white. Optimising the various parameters can produce films of the order of 50µm. The scattering properties are maintained when the films are ground into powders, says Hoelscher, so they could potentially be used in paints, paper and cosmetics.

The advantage of the technique is that ‘it could be produced on a large scale. Supercritical carbon dioxide is widely used in industry – it’s very cheap and you don’t need additional material, which is a big advantage for the environment.’ In principle, other polymers could also be used.

Hoelscher and Vignolini are together working on another promising method that might deliver more flexibility because the resultant films are thinner. Here the polymers are dissolved in a non-polar solvent (acetone) and water. Applying ultrasound to the solution over one to three hours creates longer, thinner fibrils.3 The acetone evaporates quickly, leaving the rest of the water and a polymer-rich phase which has formed a random network. The water evaporates more slowly, which leads to the formation of nanoscale pores. Unlike the beetle scales, however, the pores on the surface of the film allow water to penetrate and the polymer film becomes transparent when wet.

Growing colour

A chance finding in the harbour of Dutch city Rotterdam has led to an understanding of the genetic basis of structural colour in bacteria – and the possibility of genetically engineering living materials to use in pigments or even sensors.

A researcher from small Dutch biotech firm Hoekmine was screening bacteria for antibiotic resistance and came across an intensely coloured bacterial colony. ‘When we looked at the colony under the microscope, we already had the feeling it was structural not pigmentation,’ explains Hoekmine chief executive, Colin Ingham.

We’re trying to build 3D objects out of agar

The rod shaped Flavobacterium are densely packed together in a hexagonal arrangement that interferes with light to produce a vibrant metallic green. ‘They’re insanely organised,’ comments Ingham. Working with researchers at the University of Cambridge, the team have mapped the genes responsible for the structural colour – the first such study.4 The colour of the bacteria has also turned out to be very sensitive to certain nutrients, especially organic polymers found in seaweed, potentially opening up applications in diagnostics. Moving to Crispr gene-editing technology might enable Hoekmine to create more subtle variants of colour.

Whether it’s feasible to make scalable quantities of pigment from bacteria is an open question. It’s possible, says Ingham, to dehydrate the bacterium completely and leave the structure. But the resulting film has the consistency and brittleness of gold flake, so it’s very fragile. ‘We’re trying to build 3D objects out of agar and see how far we could push it, but biomimetics might provide a more reproducible route,’ suggests Ingham.

Given the textiles industry’s energy and water demands, together with the toxic waste produced by some dyes, Ingham suggests that ‘if you could replace that, it would have a big impact’.

There’s no shortage of ideas inspired by nature’s approach to colour, but the challenge now is to take more of them out of the lab so that synthetic colour becomes as sustainable as nature’s.

Angeli Mehta is a science writer based in Edinburgh, UK

References

1 C J van der Kooi et al, J. R. Soc. Interface, 2017, 14, 20160933 (DOI: 10.1098/rsif.2016.0933)

2 J Syurik et al, Sci. Rep., 2017, 7, 46637 (DOI: 10.1038/srep46637)

3 J Syurik et al, Adv. Funct. Mater., 2018, DOI: 10.1002/adfm.201706901

4 V E Johansen et al, Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 2018, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1716214115

No comments yet