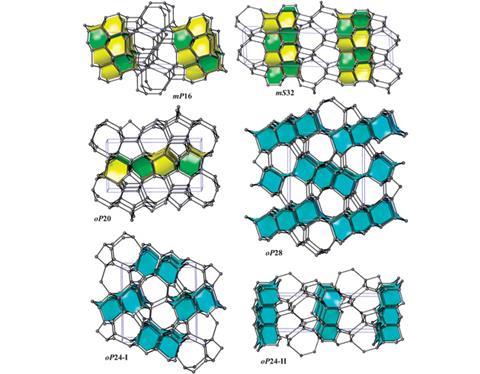

Six new forms of carbon predicted using known topologies from the zeolite field

Previously unknown carbon allotropes have been predicted by scientists exploring their links with well-known network topologies. The new structures are highly stable and transparent, some with larger optical band gaps than diamond.

Advanced computational techniques are leading the search for new forms of carbon and other group 14 elements. Now, Davide Proserpio from the University of Milan, Italy, and co-workers, have shown that fundamental network descriptors known about and catalogued for many years can help predict as well as classify and compare allotropes.

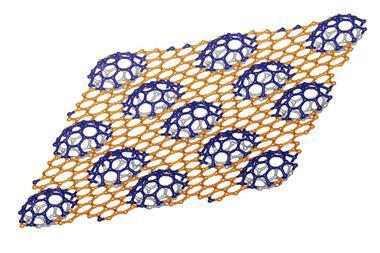

Topology defines a network in terms of its basic elements, such as nodes and links. A network can be deformed, stretched or bent and remain the same topology, but elements cannot be broken or rearranged. Zeolites and metal–organic frameworks are often described and distinguished in this way.

Proserpio’s team took a collection of 600,000 different zeolite topologies and found six new low energy carbon allotropes by applying strict geometrical and stereochemical considerations. ‘The structures are already out there but you need to feel them out with the correct criteria. A lot of people are doing molecular dynamics but no one has found these structures,’ he explains. As well as being very hard, stable and transparent, these predicted allotropes share structural characteristics with physically existing forms of carbon which points to potential fabrication routes.

‘What is important about this design work is that it draws beautifully on existing structures from one sub-field of chemistry – zeolites – to come up with possible alternatives for another field,’ says allotrope pioneer Roald Hoffmann, from Cornell University in the US. This link is important because scientists can be unaware of relevant developments outside of their immediate research area. ‘Often people are redoing things that were done in the literature a long time ago … a lot of this [allotrope] work is published in physics journals by physicists, who don’t know the chemistry,’ notes Proserpio.

Topological labelling could help prevent this duplication of effort by providing a clear system of allotrope classification. Lars Öhrström, a metal–organic framework expert at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, comments that: ‘Currently they give them [allotropes] different sorts of names, sometimes space groups … net topology will be a better descriptor than a space group, because the same topology can actually exist in several different space groups, so you can have the same connectivity, the same basic structure, but you can have different space groups.’

And there’s nothing to stop chemists from extending this topological approach to search for other new network forming compounds like water polymorphs and hydrogen bonding systems.

References

This article is open access. Download it here:

I A Baburin et al, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 2015, DOI: 10.1039/c4cp04569f

No comments yet