Bacteria killed by silver may act as vessels for the metal to kill other pathogens

The worst fears of Hollywood may yet become a reality as chemists in Israel have found dead bacteria, killed with silver, may be able rise up like ‘zombies’ and go on to kill surviving pathogens.

Silver’s application as an antimicrobial agent goes back centuries, with the metal first being used by the ancient Phoenicians to keep their water supplies fresh. In the 20th century, silver nitrate was subsequently incorporated into modern medicine, with it being given to soldiers in the first world war to stop wound infection. The metal is still applied to a range of dressings and sterilisation agents, but has been supplanted by modern antibiotics for some medical treatments in recent years. With the increasing use of antibiotics and the credible threat of antimicrobial resistance now emerging, some believe it is time to revisit silver as a standard medicine.

‘If you take an antibiotic [it] is totally destroyed when you take it,’ explains David Avnir from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. ‘Silver remains silver.’ It’s an important distinction to make, Avnir says, as silver isn’t vulnerable to the same pitfalls as antibiotics. The transition metal chemically disrupts a bacterium’s ability to produce a cell, but remains impervious to resistance.

Such an immutable characteristic raises an interesting question, Avnir says. ‘What happens to the silver after it has done its killing action?’ he asks. ‘It makes sense to assume silver inside the bacterium is such that it should behave as a reservoir for further action if it will be in the vicinity of other bacteria.’

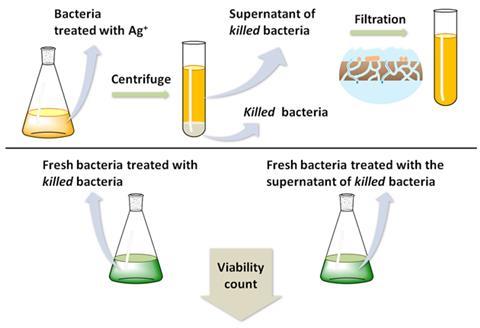

The researchers exposed Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a Gram-negative bacterium often found on medical equipment, to silver nitrate in solution. Once dead, the silver-killed bacteria were extracted and introduced to a fresh solution of P. aeruginosa. Using inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry, the team were able to measure the concentration of silver.

‘It worked even better than our expectations,’ he comments. ‘It’s a new, previously unrecognised mechanism of how an antibacterial agent kills.’

Peter Chivers from the University of Durham, UK, agrees that the research suggests that dead cells can act as silver ‘reservoirs for further killing’, but is unconvinced by their portrayal as a microscopic version of the living dead. ‘”Zombies” implies a reanimation,’ Chivers tells Chemistry World. ‘In the original use (eg in Haiti), zombies were reanimated by magic. More popularly, they are now reanimated by something like a virus. The experiments here conclusively show that the bacteria are dead.’

Pop culture semantics aside, Chivers says further work will have to be done to see whether such a technique would be viable: ‘It would be interesting to see if this also applies to a Gram-positive (e.g. Staphylococcus aureus) [bacteria].'

No comments yet