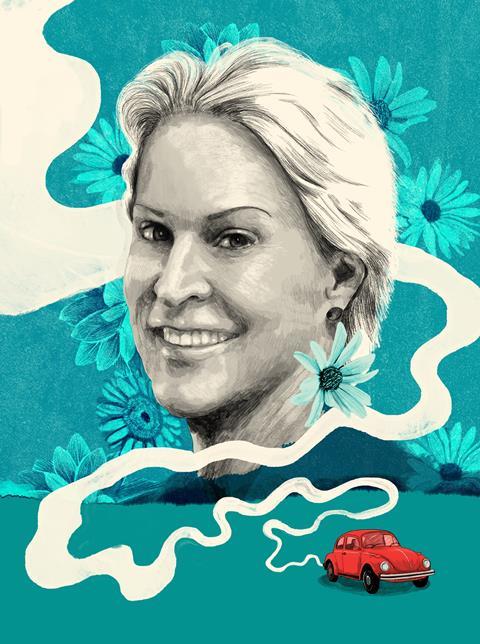

This revolutionary engineer loves to walk, travel, and learn from nature

California Institute of Technology scientist Frances Arnold is known as the pioneer of ‘directed evolution’. Her team has coaxed microbes into making silicon–carbon bonds, which had previously only been accomplished by humans in the lab. Arnold received the National Medal of Technology from US President Barack Obama in 2013, and in 2016 she became the first woman to win the Millennium Technology Prize.

I love to walk. I love to go to places and see different cities. I travel a lot, and wherever I go I walk everywhere. I have a cabin in the San Gabriel Mountains in California, and I walk there. The cabin was built by hand in the 1920s. It is in a canyon with lots of bears and even a mountain lion. It’s a real respite. There is no running water, no electricity. It is just a 20-minute drive from the California Institute of Technology and then a 3.5 mile walk up a mountain trail to get to the cabin. You walk in and carry in your own food and water. The last pack station in California is there, and they will carry bigger supplies in for you on donkeys.

I lived in Melbourne, Australia in 2003 for four months, on sabbatical. My three sons went to local schools, and it was part of an around-the-world family tour that we did. We explored parts of Australia that many Australians have never been to, like living on an Aboriginal reservation in the Red Centre for a week. My boys went feral. We camped for a week in the desert under the stars – they call it ‘the million-star hotel’. We also did a second trip to Australia in 2007, and went way out to Western Australia. We rented a 10-metre catamaran in Queensland, and my husband and I took our three boys sailing around the Whitsunday Islands.

My first car was a red 1971 Volkswagen Super Beetle. It was not quite fire engine red by the time I got it, it was already eight years old by then. It was great, got me all the way across the country. I had it until it got smashed in Berkeley by an errant driver. I would have kept it forever.

Nature is the best chemist of all time

Growing up, I wanted to be a diplomat or an ambassador. But I realised that I had no particular skills for diplomacy, though I do love languages and travel. Then I thought I would be the CEO of a multinational company, but realised that was way too much work. I had always been good at maths, and I went to college as a mechanical engineer because it had the fewest requirements.

As a young engineer, I was interested in how solar energy could be applied all over the world. But Ronald Reagan was elected US president, and it was pretty clear by 1980 that alternative energy was not a growing field, so I decided to go to graduate school in chemical engineering and join the biotech revolution. I made it to Berkeley right at the beginning of the biotech revolution.

When I first studied biochemistry is when I became excited about science. I got a degree in aerospace engineering because I wanted to work on the most complicated things that we could think of, but then when I took biochemistry I realised we can’t hold a candle to the beauty and complexity of nature. A single protein defies our understanding, yet is so beautifully functional.

No human can design a good enzyme, yet we are surrounded by them after 3.5 billion years of work by evolution. I decided that I wanted to become an engineer of the biological world, specifically a protein engineer.

I get called lots of things – a biochemist, a molecular biologist, a chemical engineer – and I guess I am all of those. I identify most as human!

All of my favourite books are all about nature as a designer, evolution as a designer. They are all about the complexity of the biological world. By far, nature is the best chemist of all time.

The biggest threat to science right now is ignorance, and people not trusting that science can help solve problems. People use fake data, or make fake claims in the guise of science, and that is dangerous. But it is also dangerous if people don’t respect scientists, if they don’t believe scientists. In the US, there is a big problem with our current leadership moving away from science and the practice of fact-based inquiry. I participated in the March for Science in April, in Washington, DC.

1 Reader's comment