Everyone needs a list of ‘things I won’t work with’

Many readers will share experience of telling someone you work in a chemistry research lab, and getting the response: ‘Isn’t that dangerous?’ My own mother had similar concerns when I started my graduate work – I told her that the most dangerous thing I did all year was the 10-hour drive back to see her and my father during the holidays, but I’m not sure that she was convinced.

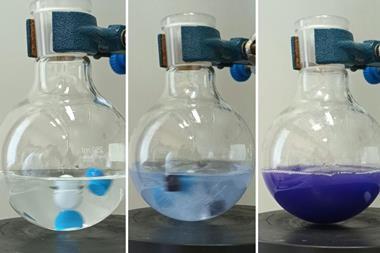

There’s a persistent belief that you’re taking your life in your hands when you do chemical research, what with the reputation for being surrounded by poisons and explosives. Of course, you can easily be surrounded by such things at home as well, but most people find that line of argument about as convincing as my mother did. The hazards are not to be underestimated – a restaurant worker was recently killed not far from where I live by ill-advisedly combining hypochlorite bleach and a strong acid cleaner and being overcome by chlorine fumes. But assuming that the average chemistry lab does have more dangerous substances in it than the average kitchen or bathroom closet. The question then arises: are any of them too dangerous?

My own line is using phosgene on a tens-of-grams scale, which I did about 20 years ago and have no particular desire to repeat

That sends us immediately into the follow-up question: ‘Too dangerous for what?’ To answer that, a risk–reward calculation is always the key. If you’re going to work with things that are toxic or spontaneously burst into flame, you’ll need a good reason and a plan to keep yourself and others safe. Almost anything can be worked with under suitable precautions, but those can range from gloves, fume cupboard and lab coat to remote-controlled armoured robot in a distant downwind location. One needs to make a rather strong case to proceed with the latter. If you’re researching new rocket propellants, that’s one thing, but if you’re making reasonable-looking analogue number 19 in a series of 38, that’s quite another.

I’ve worked mostly in situations where there are multiple routes to a desired compound. And mostly those compounds are nearly equal to several others I could be making. So my calculations always take these into account (hence the ‘Things I Won’t Work With’ section of my website). I am willing to detour to avoid certain reagents and conditions, because there are other things to do and other ways to do them. I will not, for example, use dimethylmercury. That reagent, as has been tragically proven, can sentence a person to death after months of agony if a small amount drips onto (and through) the wrong type of laboratory glove, and nothing I’m working on can balance out that risk. Similarly, I will not use nickel tetracarbonyl (volatile, hard to contain, highly toxic), elemental fluorine gas (violently toxic and reactive), polonium (lethally radioactive and toxic), or many other substances, because I can make no case for handling them.

Suitable precautions can range from gloves, fume cupboard and lab coat to remote-controlled armoured robot at a distant downwind location

No doubt there are readers who have used these (although probably not all three). Everyone makes their own calculations. I once saw a colleague in graduate school run a reaction in liquified hydrogen cyanide, and in retrospect I think that was even more of a bad idea than I thought at the time. The product he obtained (his whole project, in fact) was simply not worth the difficulty and danger. He decided differently. My own line is drawn somewhere around the level of using phosgene on a tens-of-grams scale with standard organic chemistry glassware, which I did about 20 years ago and have no particular desire to repeat. I really should have investigated more alternatives even then, to be honest.

One problem with this subject is that it tends to lead to bragging contests about who has run the most hazardous reactions. But think about it: if these reactions have all been run for good reasons with the best protective equipment there is less to brag about. And if they haven’t, then the discussion turns into figuring out who has been the biggest fool. I would rather people brag about the times that they figured out a way to avoid using chemical warfare agents or contact explosives to get their work done; that sounds like more of a test of intelligence and thus a contest more worth winning.

No comments yet