Science technicians, especially chemistry technicians, absolutely love making, tinkering with and introducing new practical hands-on activities and demonstrations to help students understand concepts and ideas. So, during the UK lockdown after Christmas, it did not come as a surprise when teachers asked us to start filming some experiments and demonstrations to discuss with their students.

As a group of three experienced technicians still lucky enough to be working part-time on site, we jumped at the opportunity. This was our chance to shine! The fact that we knew nothing about filming, lighting, focusing or editing did not curb our initial enthusiasm.

After a couple of days excitedly discussing, planning and organising the materials we began filming. At the first edit we reviewed our accomplishments – and vision and reality collided. The videos lacked commentary, captions or any form of audio (apart from the occasional clink of glassware from a stirring rod or beaker) and seemed relatively underwhelming compared with our initial Hollywood-style ambitions. We sent them off into the world with our enthusiasm dampened by our own harsh self-criticism.

No specialist cameras for us!

In our defence, it was a first plunge into something we were not used to and came with a raft of unexpected difficulties. Even things that seemed simple took ages, from positioning our smartphones (no specialist filming cameras for us!), to choosing a background that best highlighted the experimental results. We had to avoid the sporadic building noises from contractors, who seemed to start using heavy machinery whenever we hit the record button. Positioning our hands in such a way to not block any useful view of the experiment also proved challenging at times.

Suffice it to say, it took many, many takes. We often ran the risk of using all available memory in our phones, and their batteries rapidly drained from the many hours of filming. We had to restart repeatedly as glassware broke and flasks fell, and nothing seemed to focus quite as we expected. And don’t get me started on the editing….

When we tentatively sent out the first couple of videos, we did not expect much. We half expected teachers to get back to us saying ‘thanks for that but we’ll pass – YouTube is a much better resource’. To our surprise, teachers started asking for more. They liked the idea of videos without commentary, which they could pause at any point to discuss what was happening and get students to predict outcomes. They could even flip it around and ask students to explain what was happening in the video.

We got better with practice, adding titles and short captions, focusing and zooming in on analytical instruments like electronic balances and thermometers so students could ‘read them out’ and write down real data. We started to deliberately leave mistakes in, such as poor technique or minor safety hazards, to see if students could spot them.

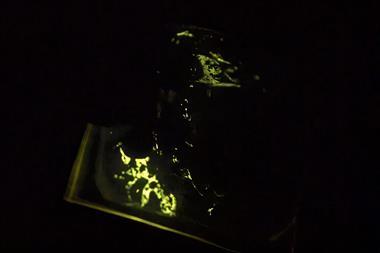

Then we began to up our game, challenging ourselves to get better and better results. We were not afraid to try new techniques. We started using visualisers and USB microscopes to show the beauty of microscale chemistry in all its glorious detail, especially while doing precipitation reactions ‘in a puddle’. In some cases, we did both micro and macro versions of a particular reaction. We began to go off script, adding demos that went beyond the curriculum or that we thought would be useful.

Biology videos tended to be easier to make, since they were more about interpreting observations and results. Physics, on the other hand, preferred online simulations that are good for collecting and analysing data, and performing calculations. Chemistry, however, needed something extra – the demonstration of good technique and how to manipulate equipment.

An unexpected highlight seemed to be seeing the school labs in use

After the videos had been used in lessons for a couple of weeks, feedback from students and teachers began to flood in. To our surprise and delight they really enjoyed the videos. An unexpected highlight seemed to be seeing the school labs in use, a place they knew well and had fond memories of spending time in. They also appreciated the videos showing a lighter side, such as when we ignited balloons filled with flammable hydrogen gas in progressively larger sizes – especially as the smartphone and tripod almost fell over from the shock wave of the largest exploding balloon.

The thermite reaction video was a particular crowd-pleaser. We decided to add a bit of extra mixture in a mini terracotta flowerpot so the students could observe molten iron plunging into a tray filled with sand. The sparks were phenomenal as they began bouncing off nearby tables. Despite a safety screen and proper precautions taken, the technician filming decided, wisely, to take a few steps back.

The addition of sound effects when a particular demo or experiment went well (applause and cheering) and the inclusion of our own laughter and comments made the experience even more relatable. In hindsight, maybe we should have kept all our mistakes, outtakes and broken glassware in frame. Students need to know that mistakes take place, but learning from them is the crucial factor. Perhaps next time though we’ll refrain from swearing so much!

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Kate Williams (senior chemistry technician) and in particular Jason Carter (senior biology technician) for encouraging the filming and of course helping me by editing the first draft of the article. Both have a wealth of experience and knowledge as technicians accumulated over many decades.

I’d also like to thank all the technicians working at St Paul’s School. We can only succeed by supporting each other. We are a phenomenal team that I’m proud to be part of.

No comments yet