Historically associated with resurrection, yew is poisonous enough to kill

With ages measured in millennia, a trio of evergreens – Scotland’s Fortingall yew, Wales’ Defynnog yew, and England’s Ankerwycke yew – are among the oldest trees in the UK. Each is Taxus baccata, a species with a designation seemingly at odds with its longevity – the tree of the dead. This menacing moniker seems to fit with where many old T. baccata trees are found in the UK – churchyards and graveyards – though a litany of myths, legends and cultural histories abound to explain the tree’s connection with the dead and the living.1,2 If struck down, T. baccata can ‘re-sprout and grow a renewing trunk or series of trunks’,1 making it a symbol of resurrection and eternal life. In the Christian church, T. baccata branches and sprigs substituted for palms on Palm Sunday in areas within this species’ natural geographical range.

The history and mythology surrounding T. baccata should see it featured in medicinal tomes from antiquity forward. Instead, one of the most influential works of early pharmacology penned in the first century CE – De Materia Medica by Dioscorides – ascribed it as having no medicinal value and warned against its use.3 Save the flesh of its berry-like seed coverings, all parts of T. baccata are poisonous.

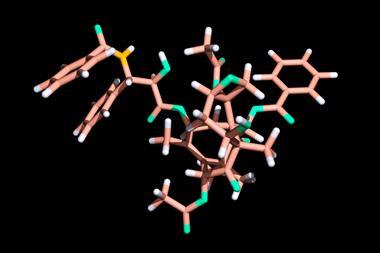

It is the compounds now known as taxine alkaloids that bear the blame for T. baccata toxicity. Most abundant and dangerous among them is taxine B, a potent cardiotoxin. It blocks the calcium and sodium channels of heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) and disrupts sodium-potassium transport that can lead to a lethal arrhythmia.4–7 Ingestion of a lethal dose of T. baccata leaves (0.6–1.3 grams per kilogram of body weight) could see symptoms strike in 30 minutes to an hour, with death potentially within two to five hours. There are no known antidotes or specific therapies.5,6,8,9

The toxic potential of taxine B certainly points to the possible use of T. baccata as a homicide weapon, like the alkaloid strychnine of the Strychnos nux-vomica tree. However, homicidal T. baccata poisonings are very rare, with the majority of reported fatal intoxications being either suicidal or accidental. But a rare method of homicide is not an impossible one – as a Canadian multidisciplinary team had to consider in their investigation into the sudden death reported recently in the Journal of Forensic Sciences.4

It all began with a video call between two friends. One friend suddenly had trouble breathing, prompting the other to call their friend’s mother who summoned paramedics. Resuscitation efforts were unsuccessful, prompting involvement by the British Columbia Coroner Service (BCCS). An autopsy mostly revealed a series of non-alarming or non-specific results. A Covid-19 test of nasopharyngeal swab materials was negative. Rib fractures noted during the autopsy were associated with resuscitation efforts. Too much fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) was observed, which is ‘a non-specific finding that can be seen in acute cardiorespiratory arrest’. Routine toxicological analysis showed caffeine, but no alcohol or prescription or illicit drugs. Gastric contents, however, showed something perhaps unexpected – ‘numerous partially digested plant-like, needle-shaped leaves and small twigs’.

This plant material was identified by experts at the University of Victoria Centre for Forest Biology as T. baccata, rather than its fellow Taxaceae family member Taxus brevifolia (Pacific yew) that also resides in the area, based on morphological differences between their leaves and stems A small portion of T. baccata leaves retrieved from the gastric contents was processed using an established alkaloid extraction procedure, with the resulting extract serving as both a reference standard and spike for a blank blood sample. Decedent and spiked blood samples were run through the same sample preparation and instrumental analysis via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS–MS). Its use allowed analysts to qualitatively and quantitatively assess various T. baccata alkaloids simultaneously. Several were detected in the decedent’s blood and the plant extract, with the ‘highest responses’ noted for taxine/isotaxine B and monohydroxydiacetyltaxine. These results were perhaps unsurprising given that the amount of T. baccata material in the decedent’s stomach exceeded the fatal range for their body weight.

BCCS investigators also probed the scene of the sudden death and delved into the decedent’s life. At the scene, branches later identified as T. baccata were found and it appeared the decedent ‘had been cooking/consuming the material’. This could be seen to rule out homicide. Investigators noted the decedent ‘had no known diagnoses of depression or suicidal ideation’. However, the decedent was known to forage for food in nearby forests. Based on all the information gathered, the coroner deemed the manner of death accidental.

Sadly, foraging can lead to accidental poisonings.10 Taxus trees must be on foraging danger lists, though another list has seen a yew revision. The ‘no medicinal value’ danger list by Dioscorides was updated late in the 20th century when taxol (paclitaxel) from T. brevifolia first showed promise as a cancer drug.11 Today, it is used to treat breast, lung and ovarian cancer, along with Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Our long fear of yews is understandable and prudent. So too is our modern use of their life-saving compounds.

References

1 R Bevan-Jones. The Ancient Yew: A History of Taxus baccata. Oxbow Books, 2016

2 M R Lee, Proc. R. Coll. Physicians Edinb., 1998, 28, 569

3 Toxicology in Antiquity. Academic Press, 2018

4 E W L Brooks-Lim et al, J. Forensic Sci., 2022, 67, 820 (DOI: 10.1111/1556-4029.14941)

5 A Pinto et al, Rev Bras Ter Intensiva, 2021, 33, 172 (DOI: 10.5935/0103-507X.20210019)

6 C M Jacobs et al, Drug Test. Anal., 2023, 15, 123 (DOI: 10.1002/dta.3360)

7 G Reijnen et al, J. Forensic Leg. Med., 2017, 52, 56–61 (DOI: 10.1016/j.jflm.2017.08.016)

8 M Vališ, et al, J. Med. Case Rep., 2014, 8, 4 (DOI: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-4)

9 E Y Du et al, Toxicol. Commun., 2021, 5, 109 (DOI: 10.1080/24734306.2021.1918898)

10 K M Shanahan et al, Mil. Med., 2022, DOI: 10.1093/milmed/usac287

11 B A Weaver, Mol. Biol. Cell, 2014, 25, 2677 (DOI: 10.1091/mbc.E14-04-0916)

No comments yet