Vigilance is the watchword when tackling bad actors in the sciences

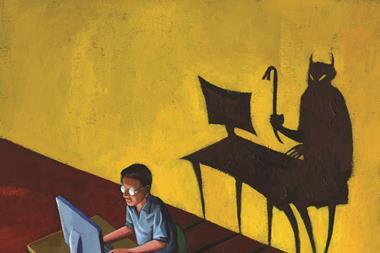

As the father of two small children I’ve recently been reacquainted with Disney’s animated classic The Jungle Book. Mowgli’s meeting with the hypnotic Kaa got me thinking about trust. The slippery snake Kaa implores him to ‘trust in me’, something that would have been repaid by a nasty end. Mowgli learns that trust should not always be given freely, an important lesson – and one that scientific publishing recently learnt the hard way.

The scientific enterprise tends to take people’s work – unless the claims are particularly wild – at face value. The science might be good or bad, novel or humdrum, but it’s assumed to be authentic. The latest story of research misconduct shows how this trust can be abused. So far, two nanotechnology scientists have notched up 14 retractions linked to images being manipulated and repurposed, with another 50 papers under scrutiny. How can science respond to researchers acting in bad faith?

Trust traditionally meant getting to know someone and cementing a relationship over time. But the scientific community has been growing at an incredible rate in recent years. One Unesco report found that the number of researchers globally had grown 21% between 2007 and 2013 to the staggering figure of 7.8 million. While many researchers will know the leading lights in their area, they’ll never meet all the people in their field, let alone spend enough time with them to build trust the old-fashioned way.

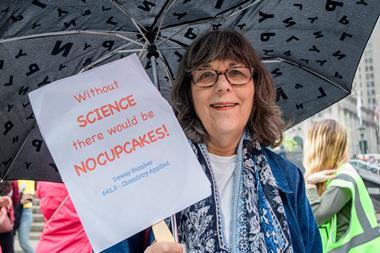

So what’s a good scientist to do? Remaining sceptical and judging each paper on its merits is a start. But, as recent instances have shown, keeping an eye out for dodgy data is now something every reviewer needs to be thinking about.

Training the next generation of scientists is vital: guidance on ethical behaviour and lessons on how to review a paper and analyse data could go some way to stamping out bad practices. Unfortunately, the ‘publish or perish’ culture can create perverse incentives and some countries have gone as far as paying big bonuses for papers in top journals. When your next promotion or cash prize rests on getting published it’s little surprise that people game the system. Strongly worded missives on ethics are unlikely to do much good.

Technology holds promise for picking up egregious data manipulation. Post-publication peer review, which helped uncover the above case, has also been a boon for the guardians of the literature. There’s no simple answer to bad actors but that doesn’t mean we should give up. Trust will continue to be a precious commodity in the sciences and vigilance needs to be the watchword that accompanies it.

No comments yet