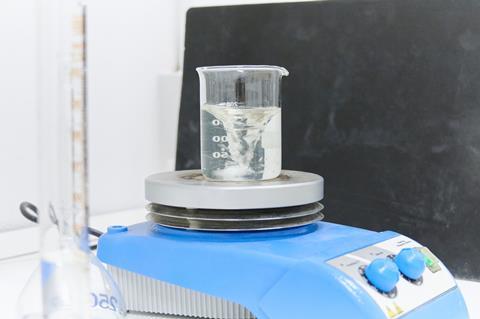

What if one of chemistry’s most indispensable lab tools was actually doing nothing at all? That’s the claim made by Zhong-Quan Liu and his colleagues at Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, who argue that stirrer bars – chemistry’s quiet workhorses – may owe their reputation more to myth than to science.

‘People generally believe that stirring helps with processes such as material dispersion, dissolution, and collision,’ the team writes. But Liu says the team’s faith in stirrer bars was shaken during an exploration of a solvent-free reaction, where they found higher yields without stirring. ‘We were very surprised,’ he says. ‘For hundreds of years, people have stirred chemical reactions, assumed stirring accelerates reactions – but in this case, it didn’t.’

For over 200 years, chemists have considered stirring an essential part of experiments. Stirring is so routine that nearly every synthetic procedure uses it. ‘Yet, chemical reactions in nature occur without stirring,’ says Liu, ‘raising the question of whether stirring is truly necessary – an idea that motivated this research.’

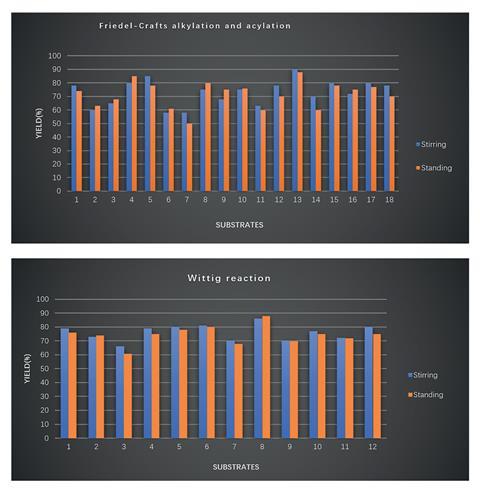

To get to the bottom of things, the team examined 329 organic reactions across eight categories and 25 types, including polar, free-radical, transition-metal-catalysed cross-couplings, oxidation, reduction, rearrangement, electrochemical and photochemical reactions. ‘This was the biggest challenge; comprehensively examining the impact of stirring on different types of chemical reactions,’ says Liu.

They tested each reaction with seven to 23 different substrates, running parallel experiments – one with stirring, one without – while keeping all other conditions the same. Some reactions were even scaled up to gram and kilogram levels to see if stirring made a difference. The result? Stirring didn’t matter.

‘This study is quite interesting,’ comments Jeffrey St. Denis, a chemist with two decades of experience in synthetic chemistry who was not involved in the study. ‘I have observed somewhat similar situations whereby stirring reactions are stopped overnight (by accident, of course) and in the morning, finding them to have gone to completion or delivering a consistent yield from previous reactions. This was always an unexpected, though welcome result.’

For a more accurate comparison, St. Denis suggests it would be good to compare the assay yield of reactions with and without a stirrer bar before workup and purification steps. ‘Repeating the reactions to at least n=3 should also minimise any differences in manipulation and handling of individual reactions and products,’ he adds. ‘It would also be nice to show a before and after picture of an exemplar reaction setup for each reaction type and note solid precipitants, gas evolution, emulsions being formed throughout the course of the reaction.’

Beyond these observations, other researchers have noted potential downsides to stirrer bars, such as contamination causing false negatives, the bars acting as ‘phantom catalysts’ or their position affecting reproducibility.

There are also potential broader benefits to cutting out stirring altogether. ‘The annual electricity consumption of China’s chemical industry in 2020 was approximately 440 billion kW/h,’ says Liu. ‘Mixing accounted for about 10%. Expanding globally, [we estimate] 1–2 trillion kW/h. That means that if agitators are stopped, the global annual energy savings would be equivalent to 10 years of power generation from the Three Gorges Dam.’

However, St. Denis is skeptical that the energy savings would be so significant, and he doubts process chemists will be quick to abandon stirrer bars. ‘Large scale industrial processes require exquisite understanding and control of heat transfer, which is facilitated through stirring of the reaction vessel,’ he says.

However, even on a small scale, where stirrer bars were shown to have no effect, old habits die hard. ‘Given that synthetic organic chemists tend to have their own particular ways of doing things, I think those who have always stirred their reactions will continue this practice until they leave the bench,’ says St. Denis. ‘I know when I really need a reaction to work, I will turn to my favourite round bottom flask, charged with my favourite stir bar set at 900rpm for the foreseeable future.’

References

X Huang et al, Syn. Lett., 2025, 36, 683 (DOI: 10.1055/a-2384-7220)

No comments yet