Ben Valsler

This week, Hayley Bennett takes us from pearl divers in Australia to Californian surfers, linked by a stretchy polymer…

Hayley Bennett

Broome, Western Australia, is a pearling town. Divers began flocking to its bays in the nineteenth century, drawn by the discovery of the silverlip pearl oyster – the world’s largest pearl-producing oyster. It was a hard life for divers; weeks spent at sea with only what you could catch to eat. Sharks and the bends were occupational hazards, and you’d be descending in hundreds of kilos of kit, including a metal helmet and weighted boots to keep you on the sea bed. There was not a scrap of synthetic rubber to be found in a pearl diver’s suit. It was canvas and baggy, with woollen layers underneath.

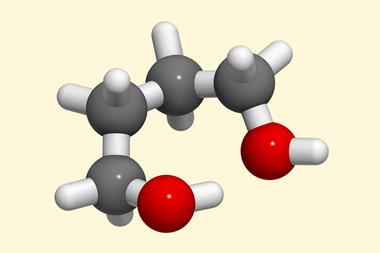

Things stayed like this for a very long time, even after new materials came on the scene. In April 1930, in the same lab that went on to produce the blockbuster fibre nylon-6,6, Arnold Collins saved an unidentified glob of liquid from an experiment. He’d been attempting to make divinylacetylene. Returning to the glob a few days later, he found a solid lump that bounced when he dropped it. The lump was a synthetic rubber – polychloroprene. DuPont was soon selling it as DuPrene, but it became neoprene.

Neoprene’s exceptional properties are its resistance to wear and tear, and to degradation by bacteria. There are different grades of the rubber, with applications from latex gloves to conveyor belts, and its properties can be improved by a chemical process called vulcanisation, which creates crosslinks between the chains of the polymer. Today, neoprene is made from chloroprene, sulfur and water in a process called free radical emulsion polymerisation. After the product is cooled and frozen, it is drawn into sheets of white rubber and then ropes, which are chopped up to form little chips that resemble pieces of halloumi cheese.

Back in Broome during the 1930s and 40s, very little was changing for the pearl divers, who carried on descending in their Hazmat-style suits and metal helmets. But in California, a young Jack O’Neill had begun bodysurfing. Surfing became his passion and in 1952, he opened the first ‘surf shop’ in San Francisco. Meanwhile, he was experimenting with PVC vests for keeping warm in the winter surf. Soon after, as the story goes, a pharmacist friend suggested trying the new material, neoprene.

It’s not clear whether it was O’Neill who invented the modern-day wetsuit or Hugh Bradner, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, who was testing prototype wetsuits around the same time, hoping to replace the rubber outfits worn by military divers. He was working with foamed neoprene, on the basis that you didn’t need to stay dry to stay warm, as long as you could trap enough air in the wetsuit material to provide insulation. To make foamed neoprene, the little polychloroprene chips – like halloumi, remember – are mixed with a foaming agent such as nitrogen and baked till the mixture expands like bread, which is then sliced into sheets.

Whoever invented it, the wetsuit started to take off for O’Neill, now the name behind the well-known surf brand. By the late 1950s, O’Neill and another company, Body Glove, were publicly promoting their neoprene wetsuits to surfers. But the Broome pearl industry remained set in its ways, despite developments in scuba diving. Finally, in the early 1970s, one pearling company brought in divers from the abalone industry where they were already getting accustomed to the new gear. The look was completed with flippers and a modern ‘hookah’ breathing system to replace the metal fishbowl-style helmet. Traditional methods in the pearl industry persisted far longer than they should have and continued to put divers at risk for many years. By comparison, many of today’s pearl divers are highly skilled marine biologists with access to decompression chambers for safety.

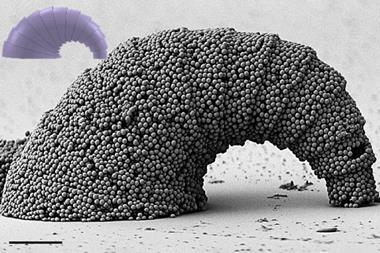

Of course, the wetsuit itself doesn’t really deal with some of the old hazards of the job. But perhaps it could. In 2013, an Australian company calling itself Shark Attack Mitigation Systems released a range of camouflage-printed wetsuits designed in conjunction with scientists at the University of Western Australia. The idea being that the standard black-dyed wetsuits might be attracting more sharks than lighter, camouflaged versions. Field testing is ongoing.

One of the main problems with neoprene is its long lifespan. It’s actually so non-biodegradable that it has been used to line landfill sites. Eco brands are now pleading with people not to dump their old wetsuits. Surfers – and presumably pearl divers – can now donate to turn their old suits into everything from dog bowls to yoga mats.

Ben Valsler

So next time you’re doing a downward facing dog in your yoga class, consider that your mat may once have been diving into the ocean to collect pearls, and in another life could have been a water bowl for a real downward facing dog. That was Hayley Bennett with the story of neoprene. Next week, Brian Clegg gets fruity.

Brian Clegg

Because of its strong resemblance to the smell of the fruit, the oily, pale yellow liquid of citral is often used to give a citrusy zing to perfumes and a citrus flavouring to sweets and soft drinks. Perhaps surprisingly, this isn’t limited to lemon flavours.

Ben Valsler

Join Brian next week to find out more. Until then, you can find all of our podcasts online at chemistryworld.com/podcasts and do get in touch if you have any suggestions. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for listening.

No comments yet