Ben Valsler

This week, Kit Chapman on how a presidential parade looked more like an avian apocalypse…

’Mr. Vice President, Mr. Speaker, Mr. Chief Justice, Senator Cook, Mrs. Eisenhower, and my fellow citizens of this great and good country we share together:

When we met here 4 years ago, America was bleak in spirit, depressed by the prospect of seemingly endless war abroad and of destructive conflict at home.

As we meet here today, we stand on the threshold of a new era of peace in the world.’

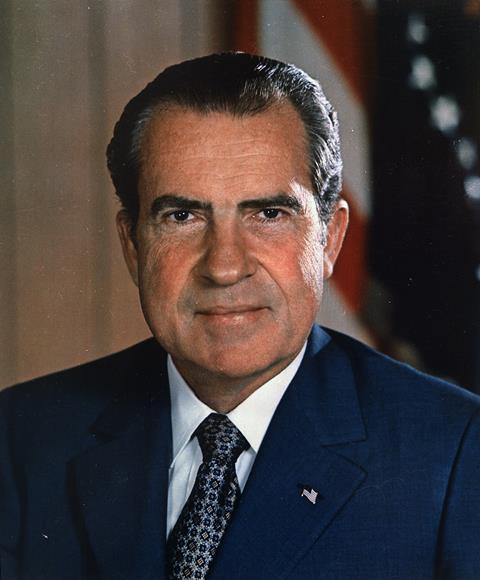

Richard Nixon’s second inagural address, 20 January, 1973

Kit Chapman

Richard Nixon has gone down in history as one of the least popular US presidents. But in 1973, Nixon was at the height of his popularity: he’d just been re-elected with 60% of the popular vote, winning in all but one state and the District of Columbia. His inauguration was supposed to be a triumphant parade. So why was the route lined with dead pigeons?

The pigeons had nothing to do with a protest. They were the result of Nixon’s own zealous attempt to make his big day go off without a hitch. In his previous inauguration, Nixon had noticed that there were a large number of birds in the trees, and didn’t like the thought of being pooped on as he drove down the National Mall in Washington DC in an open-top limo. Nixon ordered that the pigeons were to be removed – and so the US government spent some $13,000 on a pest spray, Roost-No-More, to get rid of the offending birds.

Roost-No-More’s active ingredient at the time was polybutene. This is a long chain of butylene – two carbons in a double bond, linked to two more carbons – an alkene that has a range of applications. It can be used as a plasticiser, an additive in grease, or as a sealant and adhesive. This adhesive property is why it was used: it forms a non-drying, sticky surface which isn’t fun for birds to land on, causing them to leave. It’s the avian equivalent of getting chewing gum on your shoe.

Polybutene is pretty safe. It can irritate the eyes but isn’t known to irritate the skin, and the risk to humans is generally considered low. In fact, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) even go as far as to say that polybutene ‘is practically nontoxic to birds on an acute oral and a subacute dietary basis’. Unfortunately, as the EPA’s report continues, ‘Birds whose feathers contact the sticky material may become temporarily entrapped, or their feathers may become coated with gel. When such incidents occur they can be fatal, but usually involve only one or several birds at a time.’ But then $13,000 worth of polybutene isn’t usually sprayed at the same time.

All of this meant that while Tricky Dicky was able to neatly avoid any avian scatological mishaps on his big day, he did have the ignominious fate of his motorcade rolling past the corpses of around a dozen birds that had cooed their last. It was an ill omen for the commander-in-chief pigeon murderer – within a year the Watergate scandal had cost him the presidency, and left him as a watchword for political abuses of power.

’I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interest of America first. … Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow.

…By taking this action, I hope that I will have hastened the start of that process of healing which is so desperately needed in America.’

Richard Nixon’s resignation speech, 8 August 1974

Ben Valsler

That was Kit Chapman with polybutene. Next week, Brian Clegg looks at a simple molecule with a complicated structure.

Brian Clegg

In their 2017 paper, Yury Vishnevskiy, Denis Tikhonov and colleagues describe it as a ‘nightmare of molecular flexibility in the gaseous and solid states.’

Ben Valsler

Join Brian next week to find out why it took over 150 years to determine the structure of tetranitromethane. Until then, you can find all of our podcasts at chemistryworld.com/podcasts, and if there’s a compound you would like us to cover, then email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. Thanks for listening, I’m Ben Valsler.

No comments yet