Audit of safety studies reveals shortcomings that distort our understanding of nanomaterial toxicity

A Swiss survey of over 6000 published papers on nanotoxicity has highlighted concerning deficiencies in research standards and quality.

![]()

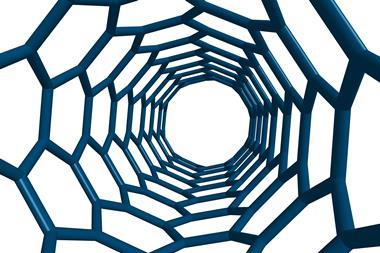

Nanotechnology research has grown immensely in the last decade and products containing nanomaterials have become more commonplace: sunscreens, wall paints and scratchproof sunglasses are just a few examples. Nanoparticles are also promising for biomedical applications like drug delivery or tissue engineering.

The size-dependant phenomena and huge volume to surface ratios of these materials mean they often have very different properties from bulk material, such as higher biological or chemical activity. However, their unusual chemical behaviour also represents an unknown quantity regarding their potential to pose health or environmental hazards.

The UK and many other European countries have therefore introduced voluntary or mandatory registers for products containing nanoparticles, and toxicological assessment of nanomaterials has become a high priority. Since 2000, over 10,000 nanosafety studies have been published, and half of them within just the last three years.

Harald Krug from the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology and University of Berne, Switzerland, set out to review this literature to assess the state of knowledge of nanotoxicology, examining some 6600 papers. However, Krug was disappointed to find that many studies had serious errors. Insufficient characterisation of materials, contamination issues, lack of control experiments and inappropriate concentrations for in vitro and in vivo studies make it difficult to reach any conclusive assessment of nanomaterials’ hazards. ‘People are disregarding the basic rules of toxicology,’ Krug complains. ‘They have used grams, not milli- or micrograms, of material per kg animal in their in vivo studies. Those concentrations, even if it was just table salt, would be fatal.’

Lack of toxicological expertise is one of the main reasons for this predicament, Krug thinks, as toxicology research has only recently experienced a surge of funding spurred by the need for nanosafety studies. ‘In Europe, many toxicology institutes were closed and now there’s a lack of well-educated young researchers,’ he says.

Krug also found a bias towards studies showing adverse effects. ‘Under the pressure to publish, people look for an effect,’ explains Krug. ‘If we want to show that a material is safe, we need to also publish studies that find no effect.’ Toxicologist Tim Nurkiewicz based at the West Virginia School of Medicine, US, agrees. ‘If everybody keeps publishing saying nanomaterials are bad, that is not a responsible conclusion, particularly if these studies are not relevant to human health.’

However, Krug also notes that consumers hoping for complete safety assurance will fall foul of a paradox of toxicology: ‘We can never prove the absence of an effect. We can, however, prove that a material is safe under the conditions and in the concentrations tested,’ explains Krug. ‘The dose–effect relationship is therefore one of the most important tools in toxicology.’

Krug thinks the way forward is to introduce a set of rules for EU-funded projects conducting toxicological studies. But Nurkiewicz would prefer scientific journals to self-police for stricter quality control.

‘Toxicological studies should lead to a pragmatic way to handle materials rather than to hysteria about effects,’ Krug says. Nurkiewicz adds: ‘We have to stop thinking about nanotoxicity just because a material is nano-sized but rather think about better toxicology in general.’

No comments yet