Hello, this week cretins, fire crackers and clean water. The story starts in Italy, and here's Andrea Sella.

Andrea Sella

When I was a child, I used spend a couple of weeks each summer high in the Italian Alps in an idyllic little village called Cogne that nestles quietly between high ice-clad peaks. To most Italians the name is associated with a sensational murder. Others know that in winter the valley has some of the finest ice-climbing in the Alps. But to me, Cogne will always be connected with the element iodine.

One afternoon, when I was around 10 years old, returning with my Dad from a long hike, we passed a dull grey building on the edge of the village. It was surrounded by a tall metal fence and had an institutional look about it. Sitting on the bench all on his own was a strange looking old man – he had rather shaggy hair, a vacant look, and a large, distended pouch of skin where his neck should have been. I was utterly shocked by this strange being. I pestered my father with questions. Who was he? What was wrong with him? Why did he look so sad?

My father, whose patience in the face of a barrage of questions was almost infinite, explained that the poor man had grown up with insufficient iodine in his diet. Iodine, he went on was essential for the proper development of the thyroid gland in the neck, and that if one didn't eat the right kind of salt, especially as a child, one might develop goitre and one's mental development would also be affected. I would later read of English travellers passing through the Alps referring to The Valleys of the Cretins – travel books of the period often include lurid illustrations of these poor unfortunates. The numbers are staggering; the Napoleonic census of the canton of Valais in 1800 found 4000 cretins in a population of 70,000 – well over 50% would have had goiter.

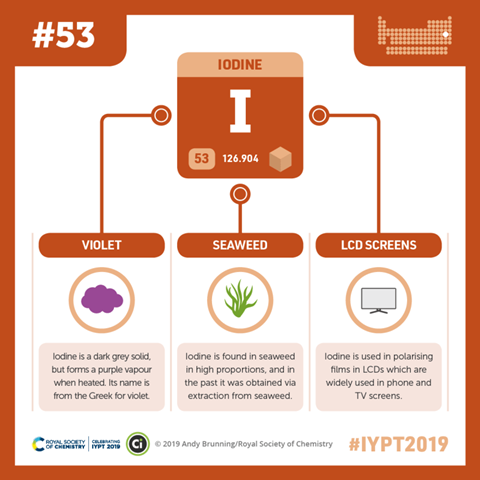

The disease had been known to medical writers for centuries. Galen for example recommended treatment with marine sponges. In 1170 Roger of Salerno recommended seaweed. Similar suggestions were also made in China.

Paracelsus, the great renaissance healer, alchemist, and writer was one of the first to spot the connexion between goiter and cretinism, and first suggested that minerals in drinking water might play a role in causing the condition. But what these mysterious minerals might be was a mystery.

In 1811 a young French chemist, Bernard Courtois, working in Paris stumbled across a new element. His family's firm produced the saltpetre needed to make gunpowder for Napoleon's wars. To do this they used wood ash. Wartime shortages of wood forced them instead to burn seaweed, which was plentiful on the coastlines of northern France. Adding concentrated sulphuric acid to the ash, Courtois, obtained an astonishing purple vapour that crystallized onto the sides of the container. Astonished by this discovery he bottled up the crystals and sent them to one of the foremost chemists of his day Joseph Gay-Lussac who confirmed that this was a new element and named it iode – iodine – after the greek word for purple. Courtois continued to play with the element and was rather shocked to discover that when mixed with ammonia it produced a chocolate-coloured solid that exploded violently at the least provocation. His contemporary, Pierre Dulong, was less fortunate, losing an eye and part of a hand while studying the material, the first in a long list of casualties from this nasty material.

The toxic qualities of iodine were soon realized, and the tincture, a yellowish brown solution began to be widely used as a disinfectant. Even today, the most common water purification tablets one can buy in travel shops are based on iodine.

It was only two years after its discovery, that a doctor in Geneva Francois Coindet began to wonder whether it wasn't the iodine in the seaweed that was the missing mineral responsible for goiter. He therefore began administering tincture of iodine to his patients by mouth, an unpleasant business, but which, he reported, led to the disappearance of swelling in 6 to 10 weeks. His colleagues, however, accused him of poisoning his patients, and at one point he was said to be unable to go into the streets for fear of being attacked.

But, while elemental iodine clearly was toxic, Coindet was on the right track, and during the 19th century by a process of one step forward two steps back the hypothesis gradually gained credence as experiments using the more palatable salt, potassium iodide, showed that goitres could be reversed. By the early 1920's Swiss cantons began to introduce iodized salt and over the following decades many countries that had been plagued by goitre followed suit, a policy so effective that many of us in the developed world are unaware of how serious a disease this had been and the word cretin has lost much of its meaning.

When I returned to Cogne last summer, I tried to remember where the institute had been. All I could find was a summer holiday camp, with children playing happily behind the gates where I had seen the old man. I phoned my Dad to ask him, and we chatted about the old days - the bad old days of the cretins – and of ghosts banished by that unique purple element, iodine.

Chris Smith

Ghosts that clearly live on amongst the British aristocracy. That was UCL chemist Andrea Sella telling the tale of Iodine, element number 53. Next week we're shining the spotlight on a substance that needs no illuminating at all and that's because it makes its own light.

Brian Clegg

It was seen as a source of energy and brightness, it was included in toothpastes and patent medicines – it was even rubbed into the scalp as a hair restorer.

But the application of radium that would bring it notoriety was its use in glow-in-the-dark paint. Frequently used to provide luminous readouts on clocks and watches, aircraft switches and instrument dials, the eerie blue glow of radium was seen as a harmless, practical source of night time illumination. It was only when a number of the workers who painted the luminous dials began to suffer from sores, anaemia and cancers around the mouth that it was realized that something was horribly wrong.

Chris Smith

And you can hear the story of Radium from Brian Clegg on next week's Chemistry in its Element, I hope you can join us. I'm Chris Smith, thank you for listening and goodbye.

No comments yet