A digital database just isn’t as evocative as the smell of the stacks

For chemists of a certain age, the word ‘stacks’ conjures twin sound and smellscapes associated with walking down the narrow canyons of library shelves, flanked by many-coloured volumes, to keep abreast of the literature. For current journals you might flip through the table of contents to see the latest news. But the search for older articles had a daunting learning curve involving several key gateways.

The indices of Chemical Abstracts occupied one end of the library’s collection of journals. You selected the decennial indices, searching by author, molecular formula or by subject. These gave you a list of cryptic code numbers like 89:463186k, each of which referred you to a short abstract buried in countless volumes further along the shelves. The abstract now pointed you to the original article, which was hidden somewhere deeper in the stacks with their unmistakable smell of books.

If on the other hand you had a specific organic molecule in mind there was Beilstein, a monumental index of almost every carbon-containing compound ever isolated. There were hundreds of these volumes, organised in an arcane, but logical, way. I remember having to attend classes to learn how these systems worked. It was dull, but essential. I remember wondering who were the cataloguers and abstract writers who spent their lives indexing chemistry for us?

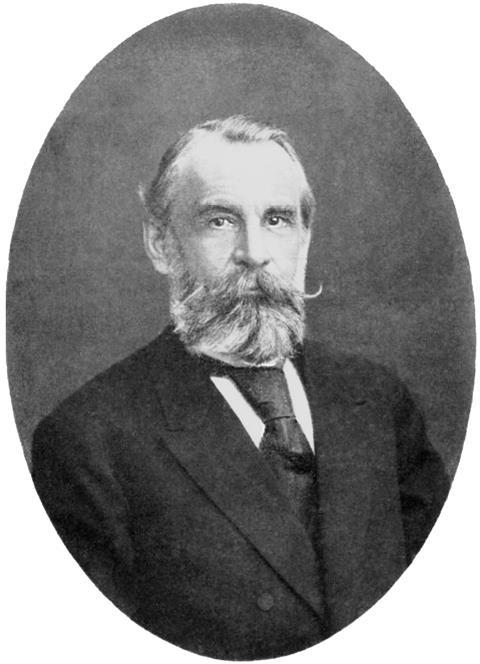

Meet the indexer

The most famous indexer was Friedrich Konrad Beilstein, a Russian-born German. After graduating with high marks from school in St Petersburg at age 14, his godfather paid for him to go to university in Germany where he studied under Robert Bunsen in Heidelberg. He then moved to Munich where he worked with Justus von Liebig and Philipp von Jolly. For his PhD, Beilstein moved again – to Göttingen, where he worked on the structure of the dye/indicator murexide with Liebig’s great friend Friedrich Wöhler.

Beilstein got his doctorate at the age of 19. After short stints in Paris and Breslau, he finally returned to Göttingen as Wöhler’s assistant. His research was on aromatic compounds. But the lack of organisation of the chemical literature bothered him. He began to make systematic notes about organic compounds, building up notebooks filled with formulas and reactions, a process that would gradually turn into an obsession that some might think a little dull.

Beilstein was anything but. He was an excellent pianist who held musical evenings at home. He loved to travel, spoke four languages fluently and got by in two more. He was a snappy dresser, a great raconteur, witty and with a fast repartee; his letters are filled with amusing and sometimes quite sharp comment about his contemporaries. But he was also something of an enigma. He seldom revealed anything about his own life and feelings, replying to questions by changing the subject or with misleading answers.

For all his travels, his dream was to go home. In 1866, he was appointed professor of chemistry at the Technological Institute in St Petersburg, succeeding Dmitri Mendeleev who moved across to teach on the inorganic side. Mendeleev would publish his periodic system the following year.

Beilstein’s position came with a comfortable flat and solid funding. He continued to work mostly on aromatic chemistry and developed his eponymous copper-based flame test for halocarbons. He was also an editor of Zeitschrift für Chemie, where he battled to get the publishers to produce formula and structural indices.

Into existence

In all this, Beilstein was in many ways deeply conservative and mistrustful of the new structural theory. As the isomers of each supposed chemical species multiplied, Beilstein’s response was ever more cautious. In a letter to his colleague Alexander Butlerov he quoted a French phrase ‘La chimie organique est la science des corps qui n’éxistent pas’ – organic chemistry is the study of things that don’t exist. Given that knowledge of the invisible chemical world was inferred from earlier, inferred chemical knowledge, how could one know that any of it was real? ‘Do these billions of compounds really exist? Just think of the myriad variants of cetyl alcohol, of which we have yet to see the end. I just cannot believe that God wanted to make life so difficult for chemists.’

Meanwhile his listings of compounds were growing. He wanted to write a textbook of organic chemistry, but the job morphed into something else. In 1880 he published his first handbook of organic compounds, one of the first cheminformatic compilations, which listed 15,000 compounds and attracted immediate attention – it was now possible for chemists to look up molecules by structure.

It was a poisoned chalice. He immediately needed to produce a second volume. And then a third. Even on holiday he would spend hours trying to organise the mushrooming literature into usable listings. Eventually, the overwhelmed Beilstein agreed that the German Chemical Society would take over from him. After his death in 1906 the fourth edition was published, consisting of 504 volumes.

By the time I started using Beilstein the volumes were hugely useful but decades behind. Today the entire enterprise has become digital and Beilstein, blandly renamed Reaxys, lies at the core of our cheminformatic searches. Millions of structures can be explored without stepping away from your desk. For all the convenience, I miss both the walk to the library and that smell.

No comments yet