Ratification of the Minamata Convention may still take five years and some green groups are disappointed by its lack of ambition

A global treaty designed to cut emissions of the toxic heavy metal mercury into the environment, took another major step forward with formal adoption earlier this month. However, the Minamata Convention on Mercury will probably not come into force for at least three years, according to those familiar with the treaty.

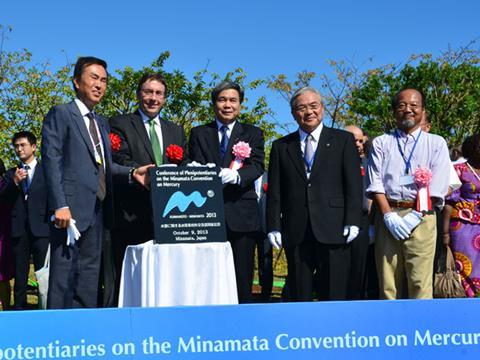

After a four-year negotiating process, the treaty was formally adopted on 10 October by 141 nations at a diplomatic conference in Kumamoto, Japan. Since then some 91 nations plus the EU have signed up, implying that they will abide by treaty regulations until it enters into force after being ratified by at least 50 nations.

Tim Kasten, head of the chemicals branch at the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which is acting as secretariat for the treaty, tells Chemistry World that official ratification ‘could take as little three years, which would be quite good’. He adds, though, that the ratification process could take up to five years.

Among the countries who have not yet signed the treaty are the US, Russia and India.

Positive outlook

Noelle Eckley Selin, an atmospheric chemist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, US, who was at the meeting in Kumamoto, does not think 91 nations signing the treaty thus far is ‘particularly low’. ‘This is the same number of countries that signed the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, which was the last major chemicals treaty and now has 179 parties,’ she says. ‘I think there is widespread agreement that the outlook is positive for the convention to be ratified by a substantial number of countries.’

The convention, named after the Japanese city where thousands suffered serious ill health or even died as a result of mercury pollution in the mid-20th century, is designed to reduce emissions and releases of mercury into the atmosphere, on land and in water and to phase out many products that contain mercury.

‘The Minamata Convention will protect people and improve standards of living for millions around the world, especially the most vulnerable,’ UN secretary general Ban Ki-moon said in an address read to the conference. ‘Let us strive to achieve universal adherence to this valuable new instrument, and advance together toward a safer, more sustainable and healthier planet for all.’

Some environmental experts, though, have expressed disappointment with the convention, saying that while it might slow the release of mercury, they do not think it will actually reduce levels in the environment.

Good first step

But many who believe that convention requirements could have been more stringent are nonetheless pleased that the international community was finally able to reach agreement on a treaty. ‘The Minamata Convention, as it now stands, is a very good step forward in tackling the issue of mercury transfer and fate for human health purposes,’ says David Evers, chief scientist for the Biodiversity Research Institute. ‘I think much more can be done for ecological health purposes and that is one direction that I would have hoped for more progress to have been made.’

Selin acknowledges that ‘treaty requirements could do more to reduce mercury in the environment’. She published a paper on the Minamata Convention in August that models what effect the treaty will have on mercury levels.1 ‘Emissions won’t go up as fast and as much as we would otherwise expect in the absence of policy,’ she says.

But, like Evers, Selin sees the treaty as a success for global efforts to cut mercury emissions. ‘It’s a major first step towards global cooperation on this issue, and should make a difference in starting to address the problem of mercury pollution at a global scale.’

No comments yet