Gene profiling firm aims to capitalise on its databank of genetic information to discover new drugs

What does it take to start from scratch in the drug discovery business? That is the question now facing US genetic profiling company 23andMe, as it plans to create a therapeutics group that will search for new leads using its database as a research platform.

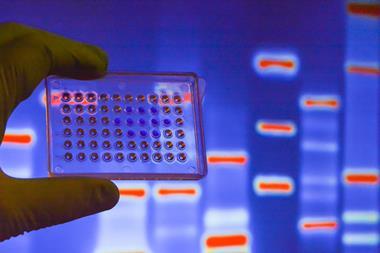

23andMe was founded in 2006 with the aim of selling genetic testing kits directly to consumers. Individuals buy the kits, collect saliva samples and send them to the company for analysis. Initially, the company provided estimates of customers’ predisposition to certain traits and conditions, some health-related, some not. The company sold thousands of kits but hit trouble in 2013 when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) ordered it to stop providing health-related information until it gained appropriate regulatory authorisation. The firm has worked with the FDA to validate its tests for a single hereditary disease, Blooom syndrome, and opened a pathway to introducing other, related tests.

In parallel, its many collaborations with researchers – in both academia and industry – have attracted more attention. In January, the company struck a deal with Pfizer that granted the pharma giant access to 23andMe’s genetic database, compiled from 850,000 individuals, 80% of whom agreed to participate in research. Now, it seems that the company has decided to go one step further and start looking for the leads itself.

The new group will be led by Richard Scheller, who was executive vice president of research and early development at US biotech heavyweight Genentech (now a subsidiary of Roche) for 14 years before his retirement in December 2014. He is a big name in the pharma industry, having won several awards, including the 2010 Kavli prize in neuroscience, for ‘discovering the molecular basis of neurotransmitter release’ and the 2013 Albert Lasker award for basic medical research. But a big name is no guarantee of success.

The practicalities of the drug discovery business revolve around three things, says Mike Westby, chief executive of Altermune, a small UK start-up company focused on immunology that launched in 2010. ‘You need people or capability, something you’re selling – which could be a product or intellectual property, or some cool science or knowhow – and you need money.’ The last of these plays a big role. The process is iterative, and you need to find the most cost effective way of running through the iterations, he explains. That may mean using suppliers who enable you to make time savings rather than cost savings. For Altermune, it has led to a transition from a virtual model, in which all services are outsourced, to a semi-virtual one, in which some in-house research is combined with work by contract research organisations (CROs).

23andMe has backers with deep pockets, not least internet search company Google, which put up $3.9 million in 2007, alongside several other companies. It raised a further £50 million through a 2012 investment round.

No comments yet