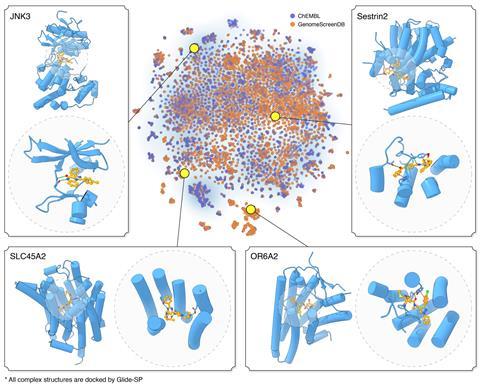

A new machine learning tool for sifting small molecules in search of good candidates to bind specific proteins requires far less computing power than previous tools. The researchers, who identified several molecules that could potentially act as drugs, hope that the model’s high-throughput screening potential could rapidly identify small-molecule ligands for every druggable target in the human genome, dramatically speeding up pharmaceutical innovation.

Artificial intelligence in protein structure prediction and design, which was awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, is extremely useful in drug discovery. However, using these techniques to find ligands to bind proteins requires a lot of computational resource. ‘Molecular docking is really slow because you need to test different kinds of angles, different kinds of poses, and you find the best one,’ says Yinjun Jia at the Institute for AI Industry Research at Tsinghua University in Beijing, China. ‘It takes a really long time even with modern CPUs.’ This helps to explain why only around 10% of the 20,000 protein-coding genes in the human genome have documented small molecule binders.

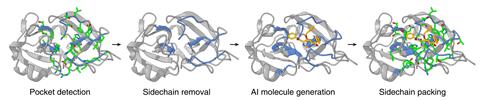

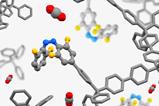

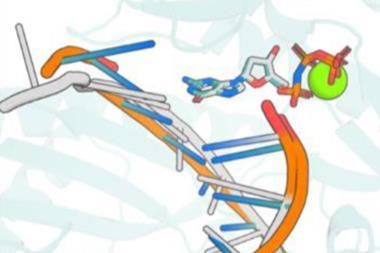

Jia and his colleagues have now developed the DrugCLIP framework, in which both the pockets in the protein and the small-molecule binders are represented as vectors in high-dimensional space. Their program then calculates the scalar product of the two vectors and uses this as a predictor of binding affinity. This formed the basis of a deep-learning algorithm, which ranks the predicted binding affinities of various ligands to target protein pockets. Finally, they use AlphaFold3 to work out the actual binding conformations of the leading candidates and ascertain whether or not they are feasible. The researchers’ screening protocol is up to 10 million times faster than docking alone.

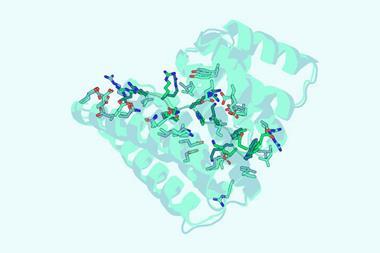

Using their methodology, the researchers arrived at new molecules for two important targets in psychopharmacology: the serotonin 2A receptor and the norepinephrine transporter. The efficacy of these molecules was confirmed in the laboratory using biochemical assays and cryo-electron microscopy. The molecule that targets the norepinephrine transporter was found to be more chemically effective than the widely used antidepressant bupropion, although Jia stresses that they ‘cannot guarantee any clinical effectiveness’. However, he adds that the team has subsequently discovered another molecule that it hopes to take to clinical trials.

Protein designer Nicholas Polizzi at Harvard Medical School in the US is cautiously optimistic. He notes that the potential for high-throughput, genome-wide screening could seek out ligands that bind a target protein without binding others, potentially leading to drugs with fewer undesirable off-target effects. However, he cautions that protein pockets are often conserved across different families of proteins, so it is difficult to ascertain whether a deep-learning algorithm has genuinely learned general principles or simply memorised aspects of the training data. Nevertheless, he says that, if the researchers pre-screening could allow scientists to conduct molecular docking simulations on a million possible ligands, and yet achieve the same accuracy as if they had tested a billon, ‘I’d say this is an extremely important problem and this would be a landmark paper, if that’s true.’

References

Y Jia et al, Science, 2025, DOI: 10.1126/science.ads9530

No comments yet