When the Brazilian government issued a new order that limited attendance at international conferences to one academic per university at the end of 2019, the country’s research community soon revolted. For domestic meetings, the education ministry (MEC) directive specified that only two academics could attend from any single institution.

More than seventy entities, including several associations, federations and societies. supported a complaint sent to the agency asking for the new rule to be withdrawn. The decree came as part of the government’s effort to reduce state spending following an 18% cut to the Brazilian education budget in 2020.

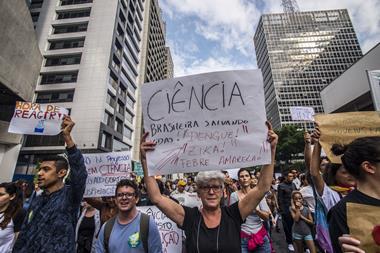

By lobbying Brazil’s Congress and initiating a media campaign, the academic community managed to get the harshest aspects of the ordinance dropped. ‘This happened due to the firm and united protests of the Brazilian scientific and academic community,’ Ildeu de Castro Moreira, the president of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC), tells Chemistry World. His organisation joined with the Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC) and penned a letter to the country’s education minister, Abraham Weintraub, in late January, requesting that his agency review the ordinance. About fifty scientific organisations signed the letter, and 20 others endorsed the complaintsome days later, according to Moreira.

In their letter, the organisations argued that the ordinance ‘inhibits interaction amongst Brazilian researchers’ and ‘undermines internationalisation and the role of national science and technology.’ Further, its authors warned that the new restrictions could make annual scientific meetings nearly impossible, hinder the participation of Brazil’s researchers in scientific forums, harm efforts to train a new generation of the country’s scientists, and cause ‘imminent risk’ to bilateral and international scientific collaborations.

In publicising the new rule and warning about its potential repercussions for the Brazilian scientific research enterprise, academic institutions gained national media attention. At the same time, several members of Brazil’s Congress took up their cause, presenting several proposals to counter the anticipated effects of the ordinance.

The MEC responded to the mounting pressure by issuing a statement promising to investigate the complaints and review the policy, as requested in the letter spearheaded by the SBPC and ABC. In its statement, the agency defended its stance, saying it ‘allowed for the possibility of expanding participants in exceptional cases, subject to the approval of the ministry.’

Government’s policy pulled

Ultimately, the MEC issued a new ordinance earlier this month that revoked part of the original decree. While the revised policy did not entirely overrule the original one, it did suppress the specific provision that limited researchers’ travel.

‘The new ordinance helped a little, but it also creates additional bureaucracy, meaning more paperwork and making things more difficult,’ says Jefferson Cardia Simões, a glaciology and polar geography researcher at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. Researchers will still have to apply for an authorisation from their university’s dean or the MEC to attend conferences, but there is no longer a cap on the number of participants from each institution.

While the Brazilian government previously required such ministerial approval, the MEC will now create a centralised register to record these travel requests made by researchers. ‘We are analysing the new ordinance to check if this centralised register will create obstacles to the participation of researchers,’ Moreira says.

In this case, Brazil’s academic community was successful in its effort to address concerns about the policies of far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, but problems persist. Since his election in October 2018, Bolsonaro’s government has instituted a freeze on federal funding that has had a negative effect on research support, and scientists in the country have reported increasing threats to academic freedom.

Despite the recent victory, it appears that there is more work ahead. ‘The science community is disappointed because universities are constantly under attack,’ Simões states. For example, he says that the government is currently looking to remove the civil servant status of professors, effectively making redundancies easier and removing other job securities. In addition, budgetary woes continue. Simões notes that government research funding has been reduced ‘to the point there are very little resources’ to fund the new and ongoing projects of young researchers, or research laboratory maintenance efforts.

Moreira says the Bolsonaro administration ‘does not consider science a priority issue,’ despite the fact that it underpins all current growth sectors in Brazil. ‘If the policy of drastic cuts continues in the next two or three years, our system will decay,’ he warns. The MEC did not reply to Chemistry World’s requests for comment.

No comments yet