The EU’s research framework programmes have fostered deep collaboration across the institutions of member states and across scientific disciplines – so what happens to those networks when a member departs?

An analysis of the efficiency and robustness of the European research network formed through Horizon 2020 suggests it is mature enough to withstand Brexit. ‘We are not saying that the R&D network is not affected by Brexit, we just say that the network is robust enough that the collaborative structure is not dramatically changed,’ says Francisco Bauzá, at the institute for biocomputation and physics of complex systems at the University of Saragossa.

The researchers likened Brexit to a ‘targeted attack’ on the network, and applied percolation theory – which assesses the robustness of complex systems when disturbed – to investigate its impact. Using data for EU projects between 2014 and 2018, they identified over 19,000 institutions and constructed a network for each pillar of the Horizon 2020 programme – excellent science, industrial leadership and societal changes, as well as an aggregate of all the programmes. In excellent science, for example, they found a third of projects had UK participation and UK institutions received a fifth of all funding.

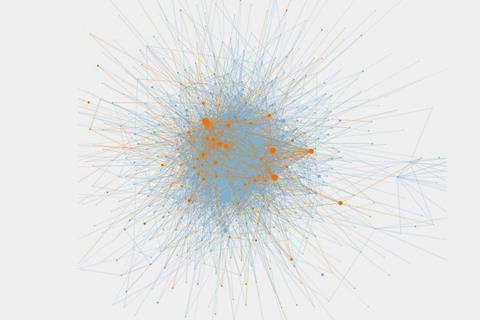

Each node in the networks they constructed corresponded to an EU institution. Two nodes were linked if the institutions had participated in the same project, with one of the two nodes being the project coordinator. The links between connected institutions were weighted according to the number of projects shared by both nodes. The researchers calculated three indicators of the relative importance of each country’s institutions to each of the four networks, as well as measures of network efficiencies. In the excellent science pillar, the UK had the second highest ranking across all three indicators.

They compared the impact of removing UK nodes, to removing the same number of nodes at random, and found that the impact varied by research programme. The loss of the UK had a significantly larger negative impact at both global and local levels – compared to randomly removing nodes – in the excellent science programme. For the industrial leadership programme, where the UK was ranked lower, eliminating UK nodes had roughly the same impact as removing nodes at random.

Renaud Lambiotte, associate professor of networks and nonlinear systems at the University of Oxford, says he was interested to discover the different roles played by UK institutions in the various programmes. But is ‘not entirely convinced’ that the methodology supports the researchers’ main conclusion. ‘For some of the network metrics considered by the authors, removing UK institutions is not significantly different from removing random institutions, but this still amounts to removing a large number of institutions that have, according to the authors, a very central location in the collaboration network.’ He adds that their analysis ‘doesn’t consider the impact of breaking many existing, long-standing collaborations that are known to take time to build.’

Lambiotte adds it would have been interesting to consider how the network would have looked had all the projects which UK universities are associated with – almost a third of them in the excellent science pillar – been removed. Bauza said they rejected this option, as it might have overestimated the impact of Brexit.

Update: Renaud Lambiotte’s name was correctedon 3 July 2020.

References

F Bauzá et al, Chaos, 2020, 30, 06314 (DOI: 10.1063/1.5139019)

No comments yet