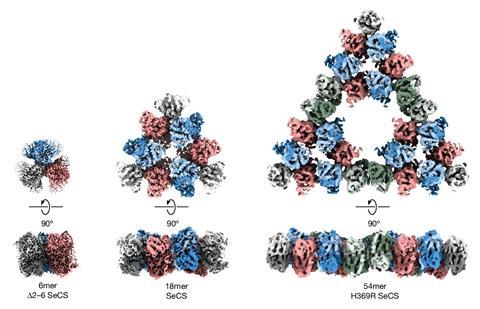

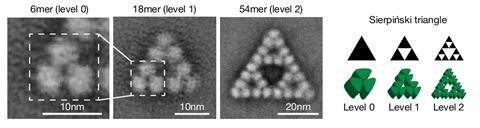

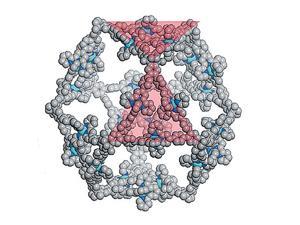

A natural protein has been reported to self-assemble into one of the best-known regular mathematically complex fractals – a Sierpiński triangle. This is the first time such a discovery has been made at the molecular scale in nature.

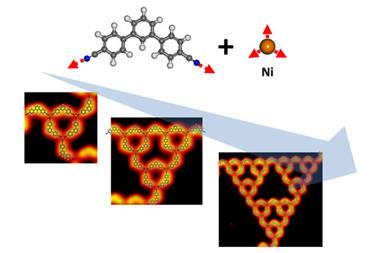

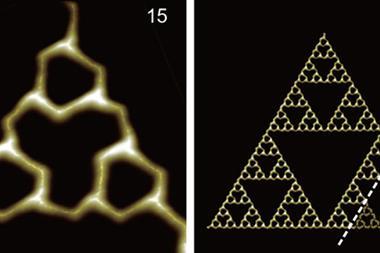

Fractals are geometric shapes that are made up of repeating smaller structures that resemble the whole. These shapes are constructed using simple mathematical rules – the patterns are self-similar across multiple length scales – resulting in geometries that are both complex and beautiful. Macroscopic fractals are common in nature – like snowflakes, river networks and mountain ranges – but are restricted to synthetic systems in molecules. Most natural fractals are irregular as their structures at different scales do not exactly match. Synthetic Sierpiński triangles have been created before on the molecular scale but these require precise experimental control.

Researchers from the Max Planck Institute in Marburg have now discovered a natural metabolic enzyme found in a cyanobacterium is capable of forming a Sierpiński triangle in solution at room temperature. Lead author Georg Hochberg says that they wanted to see what different organisms’ citrate synthase enzymes could do ‘so, we pick what we thought was a pretty boring enzyme’.

However, mass photometry of the enzyme gave the researchers a surprise. It revealed that the enzyme from the cyanobacterium S. elongatuas formed an unusually large complex for this family of bacteria. ‘We decided to take images of it with electron microscopy and out jumps this fractal,’ says Hochberg. What followed was hard analytical work to determine the origin of these structures and what they might do.

‘We had some theories that seemed pretty plausible based on what similar enzymes do in other organisms … and none of them turned out to be correct,’ Hochberg says. So they modified the microbe so that the fractal wasn’t formed and found that the bacterium was still able to produce citrate just fine. They then tested the theory that it was just an evolutionary accident – it is easy to evolve and so doesn’t need to serve a specific purpose. ‘This could just be some weird evolutionary accident. And such accidents can happen if the structure in question isn’t too difficult to build … as long as it’s harmless,’ adds Hochberg. They found that the fractal structure appeared quickly and was shockingly easy to make requiring only one single mutation. ‘We think this enzyme just stumbled into an unusual symmetry.’

The findings suggest that evolutionary transitions in self-assembly are more common than structural databases suggest. ‘It means that even aesthetically pleasing and very beguiling structures are so shockingly easy to evolve that we should expect them to sometimes exist for no good reason at all,’ says Hochberg.

‘I strongly believe that it will encourage further explorations of more natural fractal molecules in the future,’ says Kai Wu, a researcher who has constructed synthetic molecular Sierpiński triangles. ‘We obviously have to remain humble to learn from nature the aesthetic balance of complexity and simplicity.’

References

FL Sendker et al, Nature, 2024, 628, 894 (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07287-2)

No comments yet