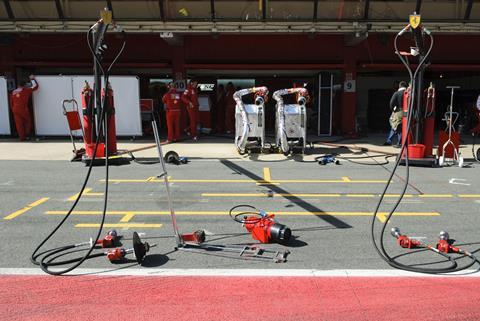

Formula One is at a crossroad. The pinnacle of motorsport is synonymous with high octane thrills and excess at a time when environmental consciousness has never been more important. The sport has already sworn to be carbon-neutral by 2030, but a huge leap is coming sooner, with a radical shake-up to how the cars are powered in 2026. But what are the changes, and can a sport known for gas-guzzling engines really go green?

The 2026 changes

The sport doesn’t really have an option, explains Peter Windsor, a former race manager who won the F1 World Championship with Williams. ‘Formula One’s power-players are very keen to see the sport along the lines of sustainability and net carbon,’ he says. ‘They all realise they’re going to isolate a small factor of the business, but they will make up for that in spades if they continue down that path. The problem, of course, is how to balance a fast-moving, noisy, spectacular TV show, now watched by a greater global audience than the Olympics or [football] World Cup, with those self-imposed obligations.’

The new direction is clear in the latest regulations changes, set to be introduced in 2026. The first major update is that teams must ensure their cars generate 50% of their power from electricity – a huge leap from its current hybrid components, which generate 120–350kW. This is on top of regenerative braking, which allows the cars to recoup about 8.5MJ per lap from kinetic energy as they slow down. ‘Going to 50% electrification is a really significant step in the minds of Formula One,’ Windsor says.

The series cannot push electric racing any further, though. In 2011, motorsport’s governing body the FIA conceived an electric car series – Formula E – and gave it the exclusive licence for electric single-seat racing. This rival series has already improved energy storage so much that it’s gone from using two cars per race (because the batteries would run out) to completing a full race with energy to spare; and has now branched out into off-road electric racing, which has attracted teams run by world champions Sir Lewis Hamilton and Nico Rosberg. Similarly, other green alternatives to traditional fuel, such as hydrogen power, are non-starters: the technology isn’t ready. While prototype racers have been developed, a hydrogen-powered series at the Le Mans 24 Hours has been delayed until at least 2027. Formula One is painted into a corner: it needs to stick with hybrid engines.

If anybody’s going to find [the solution] for the world, it’s Formula One

There’s only so much teams can do to improve their machines, too. An F1 car already has the most efficient internal combustion engine on the planet – operating at above 50% thermal efficiency, compared with a typical road car’s 30%. This, combined with the better batteries, has cut the amount of fuel the cars need for a race from 160kg a decade ago to just 70kg – the equivalent of a full tank in an average car. But it still isn’t enough to hit the sport’s goals. Instead, the 2026 rules are looking at the fuel itself.

Sustainable fuels

Currently, Formula One cars run on E10 fuel, which contains 10% ethanol, produced from crops such as corn. This quota was only introduced in 2022, and, on paper, would leave F1 lagging behind its competitors – Nascar in the US has been running on 15% ethanol since 2011. However, not everything is as it seems. ‘F1 is innovating, and Nascar is marketing,’ says Diandra Leslie-Pelecky, a physicist and part of NBC’s Nascar commentary team. ‘You can get E15 at the gas station – this was something the ethanol people thought was a good way to raise their profile. But as soon as [Nascar made the switch] the mileage went down – it’s not a particularly efficient fuel. In Nascar, it’s all about marketing.’

Formula One’s interest isn’t so superficial – and its plans are far more radical. From 2026, all fuels used by the teams (who each have their own supplier) must be from fully sustainable sources. The FIA’s requirements to approve a fuel for use also require it to be a drop-in technology: something that can be used in any of the 1 billion road cars in the world still using a petrol engine. That means creating fuel from non-fossil sources.

It’s an innovation the championship has seen coming for years. In 2019, Paddy Lowe, a team principal who has won the world championship 12 times with teams including Williams, McLaren and Mercedes, quit the sport to become the co-founder of Zero, specialising in making non-biological, carbon-neutral ‘e-fuels’, made with electrolysers. The company’s investors include former F1 World Champion Damon Hill, and Zero has already signed to supply e-fuel to the Sauber team for 2026. Zero isn’t the only company chasing e-fuels either: Aramco, owned by Saudi Arabia, has also been moving into synthetic fuels, and is set to supply the Aston Martin F1 team, while Exxon Mobil are also producing their own e-fuels.

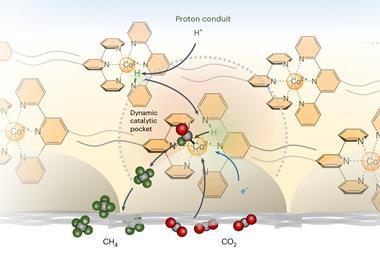

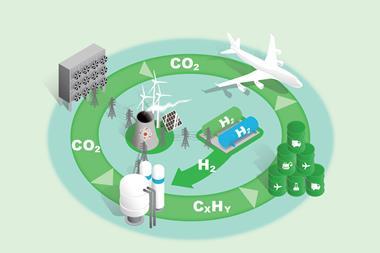

These synthetic fuels use water and carbon dioxide from the environment to create their hydrocarbon chains. First, you take water and split its molecules into hydrogen and oxygen using electrolysis. Simultaneously, direct air capture (DAC) is used to trap carbon dioxide from the air; there are a variety of different methods, for instance by using sodium hydroxide as an adsorbent. Hydrogen from the electrolyser and carbon dioxide from DAC is drawn into a reverse water–gas shift reactor, turning carbon dioxide and hydrogen into carbon monoxide and water. (Lowe points out that this can be done with electrolysis, too). Finally, carbon monoxide and yet more hydrogen from the electrolyser are mixed to create syngas, which then undergoes the Fischer–Tropsch process. First developed by Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch in 1925, this is a series of reactions using metal catalysts (usually iron or cobalt) that run at temperatures of 150–300°C and high pressures, cleaving C–O bonds and forming C–C bonds. The result is that, from about 1.46kg of water and 3.07kg of carbon dioxide from the air, you can produce 1kg of hydrocarbon and 3.53kg of oxygen.

This method of production is nothing new. During the second world war, around 9% of fuels used by the Germans were produced by the Fischer–Tropsch process. Yet while e-fuels seem as impressive as the Haber process, they have very similar drawbacks: running an electrolyser and a series of high-temperature, high-pressure reactions is energy-intensive, which could end up producing more carbon emissions than are saved. This means one of the biggest unanswered questions is scalability: while enough barrels of e-fuels can be made using power from renewable energy sources to supply the teams, it’s unclear whether synthetic fuel can make a difference on the road.

Corporate interests

Is this just greenwashing? In 2022, Formula One’s own report found that of the 256,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions during the 2019 season, only 0.7% came from the cars themselves: 45% came from the logistics of moving the cars and equipment around the world, and 27.7% from transporting staff to the events. However, while Formula One’s sponsors are still dominated by oil companies (‘it would be a big hole in Formula One’s business model if all the oil company money disappeared,’ Windsor says,) it is also not fair to dismiss these changes as a smokescreen for corporate activity.

‘The engineers at the oil companies, to which I’ve spoken, have all said that there’s quite a lot of room to being doing some stuff,’ Windsor says. ‘They like that synergy, between working with an engine supplier in Formula One and having to build a formulated special fuel.’ The change in focus also determines who the sport attracts, Windsor adds. ‘It’s interesting that, with the 2026 regulations becoming ever-nearer, we have new manufacturers coming into the sport on the back of that. Audi is the most obvious, but also Ford and Honda are making returns.’

It’s this shift that gives the greatest clue as to what’s going on behind the scenes, says Leslie-Pelecky. ‘Motorsport is tethered to what the manufacturers and sponsors want to do,’ she says. ‘The disadvantage is that they’re tethered to who wants to get behind [an idea], both intellectually and economically. But the positive side is that there’s leverage there.’ Introducing a technology like e-fuels into a sport also educates the fans about the latest scientific advances, with Formula One acting as an influence on public perception. ‘I bet a lot more Nascar fans know about ethanol because, every stage break, they wave a bioethanol flag!’ Leslie-Pelecky adds. ‘It’s a huge lever, because you’ve got people paying attention.’

And while sustainable fuel is only one step to the sport becoming carbon neutral by 2030, F1 can point its detractors to an astonishing legacy of innovations that have come from motorsport: from safety changes to turbochargers, better power and energy density in car batteries, active suspension, carbon fibre, disc brakes and aerodynamics that improve fuel efficiency. As the fastest R&D lab on the planet, it might be the kick needed to find answers to some of the questions around e-fuels. ‘Formula One is an engineering-led sport,’ says Windsor, ‘and the pace of development of any engineering exercise in Formula One probably exceeds that of any other discipline, including Nasa … if anybody’s going to find [the solution] for the world, it’s Formula One.’

No comments yet