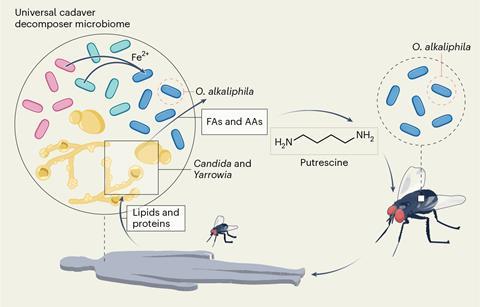

The decomposition of animal flesh is driven by a unique community of around 20 microbes, likely transported in by insects, new research shows. The researchers hope their findings will support the development of a robust forensic tool that could provide crime scene investigators with a more precise way to determine the time since death.

The researchers compared the microbial response to decomposition in 36 human cadavers located in three terrestrial environments across two climate types (temperate versus semi-arid) within the US. During the first 21 days of decomposition the team collected skin and soil samples for each body and used multi-omic data to provide a comprehensive view of the microbial ecological responses.

They found that a universal microbial decomposer network assembled in the cadavers – regardless of season, location and climate – to synergistically break down the organic matter. This network was phylogenetically unique and rare across non-decomposition environments although the overall composition of microbial decomposer communities did vary between different climates and locations.

The researchers said that key members of the microbial decomposer network were also associated with swine, cattle and mouse carrion suggesting that they were not human-specific. They also said that, based on existing lab studies, the microbes were likely to be maintained or seeded, at least in part, by insects such as carrion beetles or blow flies.

‘These findings may contribute to society by providing potential for a new forensic tool and for potentially modulating decomposition processes in both agricultural and human death industries via the key microbial decomposers identified here,’ the researchers concluded.

References

Z M Burcham et al, Nat. Microbiol., 2024, DOI: 10.1038/s41564-023-01580-y

No comments yet