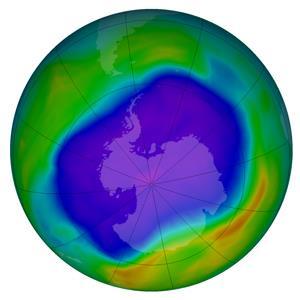

UN Environment Programme’s latest research finds ozone layer is thickening in places

The ozone layer that protects life on Earth from harmful UV rays is showing promising signs of recovery, according to a report issued by the UN Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organisation. Although levels of ozone depletion remain high, the rate of depletion has not increased for over a decade and in some places there are signs of the layer thickening.

In 1987, an international treaty, the Montreal Protocol, was established to phase out or ban the use of ozone damaging chemicals, including chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) once used in refrigerators and deodorant sprays. Now, the latest report compiled by around 300 scientists as part of the treaty’s requirements suggests that the ozone layer is on course for recovery thanks to the ban of culprit chemicals.

CFCs and similar compounds deplete ozone because when they reach the stratosphere, UV light breaks them down to release chlorine or bromine atoms, which in turn form active species that react with ozone. Ultimately, this produces oxygen while the chlorine and bromine atoms are freed up once again to react with, and thus deplete, more ozone.

‘The Montreal Protocol has been very successful in limiting the damage to the stratospheric ozone layer,’ says Johannes Laube, a co-author of the report and researcher at the University of East Anglia, UK. ‘Had CFC production not been stopped, we would face a much thinner ozone layer today and this would have had disastrous consequences, including millions more skin cancer cases.’

Moreover, the protocol has also inadvertently become the most successful global climate treaty to date. ‘CFCs turned out to be powerful and very long-lived greenhouse gases so curbing their emissions last century means we will avoid an even warmer 21st century,’ explains Piers Forster, who investigates climate change at the University of Leeds, UK.

Forster says the report is great news. ‘But I might keep the champagne on ice for a few decades yet as the ozone layer is far from recovered and we must keep monitoring emissions of ozone depleting substances and the state of the ozone layer,’ he says. ‘Nevertheless, the Montreal Protocol has been a huge success story for science, global cooperation and environmental policy.’

A full recovery of the ozone layer will be a slow process. ‘Although the most potent ozone-depleting compounds have been phased-out and their emissions have declined considerably, many of them are quite inert and it will take between years and centuries before they are fully removed from the atmosphere,’ explains Laube.

Meanwhile, there remain additional causes for concern. Some controlled gases are still being emitted into the atmosphere, including carbon tetrachloride – likely through illicit production and usage. Other compounds, such as the potent greenhouse gas nitrous oxide, are depleting ozone but are not controlled by the Protocol. And Laube’s own research has recently detected four new ozone-depleting chemicals in the atmosphere, two of which are still increasing.

‘It is entirely possible that we will get back the full ozone layer before the end of the century, but we need to keep up the good work,’ Laube says. ‘Current depletion is still high but has not gotten worse for over a decade now.’

No comments yet