For over 3000 years ancient Egyptians believed that by preserving their bodies, their souls would live on for eternity. This may explain the lengths they went to in sourcing some of the oils and resins used in the mummification process, according to results from a new chemical analysis of residues recovered from ancient Egyptian embalming vessels. The containers were discovered in a mummification workshop at the ancient site of Saqqara in 2016, and were inscribed with the names of their contents. While some of these names were known to Egyptologists, for the first time chemists have been able to match them to the exact recipes used over 2500 years ago.

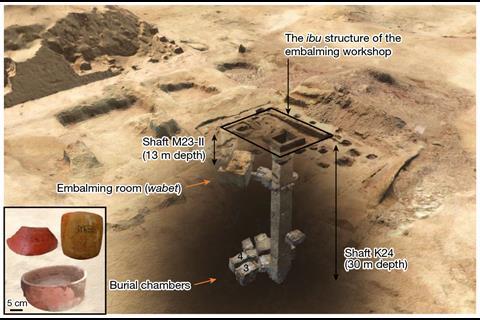

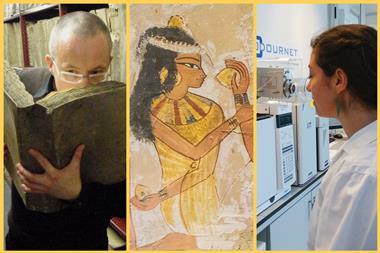

The German–English team of researchers from Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich and the University of Tubingen, in collaboration with the National Research Center in Cairo, analysed the chemical residues from 35 of the 121 vessels excavated from an underground workshop and burial chamber that has been dated to 664–525BCE. The preparations within the containers were used in the 70 day mummification process, which first desiccated the body using natron, a mixture of sodium carbonates, before treating it with specific resins and oils known to have anti-microbial and anti-fungal properties.

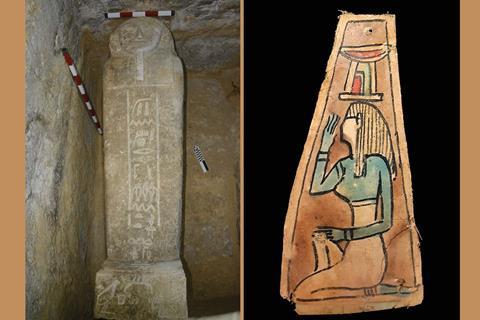

The vessels sampled were all clearly labelled in hieratic – simplified hieroglyphs – with instructions for where they should be placed, such as the head or skin. Using GC–MS the team identified residues including conifer tree oils, animal fats and beeswax. They were also able to identify a substance known as antiu, which had previously been translated as myrrh, was in fact a mixture of several oils or tars including cedar, juniper, and cypress and animal fat.

Another unknown substance called sefet was identified as a scented fat-based formula with plant additives. ‘This highlights the importance of chemistry to identify what was actually used, rather than the embalming materials utilised being based on supposition,’ says co-author and archaeological chemist Stephen Buckley from the University of York. ‘The recipes identified were complex and clearly several natural products were mixed together before being employed in the mummification. This gave complex “chemical fingerprints”, which were challenging to interpret to some extent, but this is the nature of this sort of research.’

One of the most surprising findings was the presence of dammar gum, a tree resin obtained from south-east Asia and elemi resin, which can be found in south-east Asia or tropical Africa, indicating the extensive trade routes in place at this time. Dammar, a triterpenoid resin, has antibacterial, antifungal and insecticidal qualities, similar to other coniferous tree oils sourced from the Near East. ‘It is exciting to secure actual evidence of long-distance contact,’ says Carl Heron, director of scientific research at the British Museum. ‘There is much more exciting research to be done in this field to pinpoint the geographical region(s) where these substances came from.’

Heron says previous research on the chemistry of embalming practices has often relied on limited samples, which means some ingredients have undoubtedly been missed or misinterpreted. ‘[It’s] quite rare to discover such a context and for the samples to be made available for analysis,’ he adds.

References

M Rageot et al, Nature, 2023, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05663-4

No comments yet