The highest status individual in copper age Iberian society was a woman, not a man as was previously believed. The discovery is the result of an analysis of peptides extracted from tooth enamel taken from ancient remains found in a tomb in southern Spain.

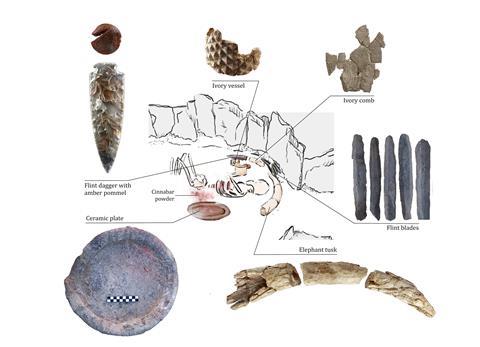

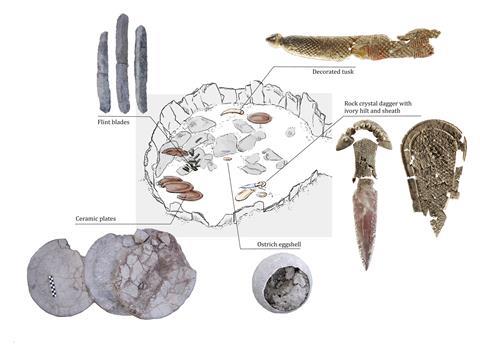

In 2008, the remains of an unusually high-ranking individual were discovered in a copper age (3200–2200BCE) tomb in Valencina near Seville. The person – who was initially believed to have been a male between the ages of 17 and 25 – was buried with an extravagant array of objects including multiple flint and ivory items, and a full tusk from an African elephant, weighing almost 2kg. A ceramic plate bearing chemical traces of wine and cannabis was also discovered in the tomb.

Other objects had later been brought to the tomb as offerings, including an intricately decorated dagger made of rock crystal and ivory. No other burial chambers from this era have ever been discovered with such a lavish array of treasures, suggesting that the person found in Valencina was of exceptionally high standing in copper age Iberian society.

Now, a research team led by Marta Cintas‑Peña from the University of Seville has analysed the enamel of a molar and incisor of the body found in the tomb. The team was specifically interested in analysing the peptides from amelogenin – a sexually dimorphic enamel-forming protein that tends to be well-preserved in archaeological samples.

The results suggested that the individual had an AMELX gene, but no AMELY gene meaning that their chromosomal sex was female – suggesting that the ‘Ivory Man’ as she had previously been known, was actually the ‘Ivory Lady’.

The researchers note that the discovery adds further weight to the idea that women held the most important positions of power in copper age Iberian society. The team adds that while many scholars over the last 200 years dismissed notions of early matriarchal political systems in western Europe, this latest finding ‘opens the door to reflect on the role that 19th century discourse about wealth and gender play in modern interpretations, and the power of new scientific methods to challenge long-standing narratives of the past’.

References

M Cintas‑Peña et al, Sci. Rep., 2023, DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-36368-x

No comments yet