Billion dollar innovation fund called for to kick-start antimicrobial drug research in the UK

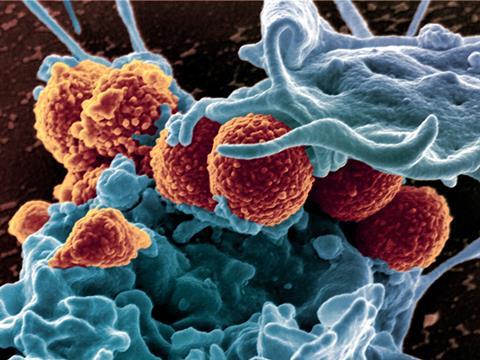

The second instalment of a UK government review on antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has called for governments around the world to focus on ‘easy wins’ in the fight against microbial resistance. Economist and chair of the review, Jim O’Neill, says governments, charities and funders need to come together now and put serious money into ‘blue skies’ research and back the best projects. This latest report comes on the heels of stark warnings made in the first report in December warning that 300 million people could die by 2050 as antimicrobial drugs become less and less effective.

Five specific actions are recommended in the report, the first being a call for an AMR innovation fund to support basic research and act as a non-profit incubator for more mature ideas. Too many good ideas are not being pursued because the money is not there and public and charitable funders must do more, the review claimed.

The US National Institutes of Health funnelled, on average, $341 million (£225 million) into AMR each year, over the last five years, just 1.2% of its grant funding. The equivalent sum for cancer research was $5.2 billion. Figures in Europe are no better. The start-up UK fund for AMR research is a paltry £25 million.

‘That would hardly buy you a fighter plane. It’s peanuts really,’ says Tom Simpson, a chemist who works on antibiotic synthesis at the University of Bristol, UK. ‘Antibiotic resistance and the lack of new compounds is a major problem. I don’t think people are aware of how many people die each year from infectious diseases. It’s a bigger and more immediate problem than global warming and it is not getting the resources it requires.’

O’Neill says the innovation fund will probably be $1–2 billion and hopes to have more details by the spring. It is not clear who will contribute yet, although the Wellcome Trust has been mentioned.

Chronic under-investment in researchers to tackle this problem is another of the five key problems highlighted. ‘AMR is failing to attract the new generation of researchers it needs in academia and public and commercial labs,’ the review noted, and there are concerns about recruitment of infectious disease doctors in hospitals. This problem is compounded by the fact that large pharmaceutical companies and their research teams are withdrawing from the field, with a loss of institutional memory and experience. And the incentives to recruit new infectious disease specialists are absent.

The review noted that HIV and infectious disease doctors were the lowest paid among 25 medical professions, and infectious disease had the second lowest application rates. ‘What really seems to fire up undergraduates when they are applying for PhDs is cancer research and I don’t know why that is,’ says geneticist Chris Thomas at the University of Birmingham, UK.

‘There is a problem with the troops on the ground, particularly with medics not really wanting to take part in infectious disease research because of how medical careers are structured and indeed financial returns,’ says Chris Dowson, infectious disease microbiologist at the University of Warwick, UK, who contributed to the report. ‘Infectious disease cuts across all areas of medicine, but is itself almost a jack of all trades.’ Money follows patients and patients are assigned cardiologists or cancer specialists, not infectious disease specialists.

Plenty of blame to go around

Dowson points the finger of blame at funders too. ‘Historically and currently it is very difficult to get research funded that involves chemistry and biology – almost impossible – apart from the Wellcome Trust. If chemistry is not new and cutting edge, it is hard to get funding to integrate it with some fundamental biology that could really push forward drug discovery.’ He adds that the EPSRC no longer provides good support to organic chemistry, compounding the problem. ‘The EPSRC needs to have a long hard look at how it funds chemistry. They are pushing hard for physicists and engineers to get them involved with diagnostics, which is fantastic, but new antimicrobials are going to need chemists. They are not going to come out of thin air.’

Another issue is that conditions such as arthritis, heart disease and Parkinson’s all have charities that fund research. ‘There is no charity aimed at antimicrobial research, and yet antibiotic resistance affects everyone,’ observes Simpson, who says he was amazed to see doctors’ pay for infectious disease in dead last.

The O’Neill review also argues that existing drugs can be made to go further by testing combinations or changing the dosage. ‘This includes identifying compounds, and compound combinations, that are already out there, that had gone through the hard discovery process, and perhaps even the harder regulatory process. We might be able to make some really rapid progress here,’ says Dowson.

Spotting disease early

A much more important role for diagnostics was also emphasised, which O’Neill has described as a ‘Google for doctors’. A joined up digital approach would improve real time global surveillance, the report argues. Dowson says action here will require coordinated action from governments.

‘My focus would be on much more rapid diagnostics. One needs to identify people with resistant organisms before they go to hospital,’ says Julian Davies, a microbiologist at the University of British Columbia, Canada. ‘But there is also a problem with clinicians and doctors. They feel they don’t need fancy scientists telling them what to do.’ He remains optimistic though: ‘There is absolutely no shortage of antibiotics in nature. We just have to isolate them.’

David Williams of UK drug discovery company Discuva expresses some reservations about the ‘fuzziness’ of the innovation fund and whether it would be truly available for SMEs. ‘What we are doing is what pharma were trying to do 20 years ago – we are filling that gap with new antibiotic therapeutics, and that might not be seen as the academic basic “blue skies” research that can lead to translational results and so we might fall in a gap in terms of the O’Neill review. But we will wait and see, since the next part of the review will be on incentives to drive the economic model.’

In terms of funding Williams praises the Innovate UK model, with matching funding for translational research. ‘If you put out too much money with no strings attached, everyone will come out of the woodwork,’ he says. ‘There is a little bit of keeping you honest if you have to put up matching funding.’

The next paper to come out of the AMR review group will be published in spring and will look at how to stimulate private investment in antimicrobials and develop new drugs and diagnostics.

No comments yet