Peer reviewers were more likely to reject papers from female authors, especially if the reviewer was male

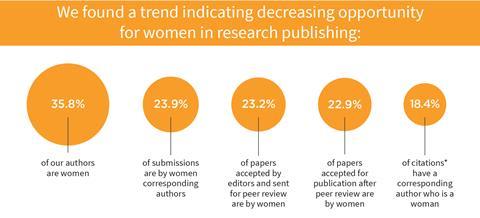

Female chemistry researchers experience subtle but significant bias at every step of the publications pipeline, from submission to citation. The result, says the Royal Society of Chemistry, puts women at a ‘significant disadvantage’.

An analysis of the gender profile of the authors of 700,000 submissions to the RSC’s 40-plus peer reviewed journals, reveals that women are less likely to be corresponding authors; are less likely than men to seek to publish in journals with a higher impact factor, and are more likely to have an article rejected without review.

Nicola Gaston, co-director of New Zealand’s MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, and the author of Why Science is Sexist is ‘not in the slightest’ surprised by the findings – ‘and the very clear evidence of the effect of networks’.

Looking at article submissions received between 2014 and 2018, 35.8% of authors were women – which is a similar proportion to that of female researchers in the chemistry community, according to analysis carried out by RSC data scientists. Compared to this baseline – and taking into account skewing caused by some authors having submitted many articles – the RSC found that women submit papers as the corresponding author less often than as the first author – 23.9% of submissions had female corresponding authors and 33.4% of submissions had female first authors. Women are even less likely to be the sole author of a paper – only 19.6% of sole-authored submissions are from female authors.

At the subsequent stages, the RSC found further small biases that disadvantage women. 25.6% of papers that were rejected without peer review had a female corresponding author and 34.2% of those papers had a female first author – both slightly more than the percentages of submissions with female corresponding authors (23.9%) and with female first authors (33.4%). And when it comes to accepted manuscripts, just 22.9% come from female corresponding authors and 33.1% from female first authors.

Female corresponding authors are less likely than their male counterparts to receive a positive outcome of ‘accept’ or ‘minor revision’ from a reviewer, and are more likely to be rejected or to be asked to make major revisions. But biases work the other way too, with female reviewers more likely to accept or recommend minor revisions from female corresponding than male corresponding authors.

By the time it gets to citations, papers by female corresponding authors are cited on average 5.6 times, compared to 7.2 times for men. Men cite female corresponding authors less often than male authors and, while women cite fewer articles overall, female corresponding authors cite women more than men do.

Amongst its commitments to redress the balance, the RSC says it will publish an annual analysis of its authors and calls on other publishers to do the same. It will recruit and train reviewers (currently 24.5% of RSC reviewers are women) and editorial board members to more closely reflect the current gender balance – aiming to reach 36% by 2022; and investigate new publishing models such as double blind or open peer review.

The RSC has carried out the first in-depth gender analysis of each stage of the publication process within the chemical sciences community. The report also contains views from the chemical science research community about the biases within publishing, the factors that might be contributing to these biases, and what the RSC plans to do to tackle them.

Emma Wilson, director of publishing at the RSC, says the quality of the science will remain the main criterion for publication, but ‘our challenge to all those in the research ecosystem … is to follow our lead and take an objective look at themselves, as it’s going to take everyone working together to make a difference.’

Gaston suggests concrete steps are required. ‘We have to ask what changes can we make to the system – even if you can’t insist yet that you have completely equal outcomes.’ At the stage of deciding whether a paper goes to reviewers or not: ‘there is a case to be made that you set up a system of equal probability of getting through whether [you’re] a male or female author. Rather than giving the editor the power of yes or no, give a numeric value – 1–10 from “don’t review” to “review” – and adjust the value that is the cut off, by gender.’ She acknowledges ‘it is hard when you start looking at fixing the problem. But we have to look beyond transparency and education. They’re prerequisites.’

1 Reader's comment