When Clare Mahon went to do her laundry one August day in 2022, she didn’t know it would lead her to uncover a colourful reaction between two common consumer products.1

‘I had a white T-shirt that had a sort of greasy-looking stain on it, and I washed it a couple of times and I couldn’t get rid of this stain,’ she recounts. ‘And because it was a white T-shirt, I pegged it out on my washing line and I sprayed it with bleach, and it immediately went bright red!’

It was a strangely fortuitous mishap to befall an organic chemist, not least one leading an industrial partnership looking at the science behind stubborn fabric stains. ‘I took a picture of my T-shirt and I sent it to my colleague Andrew Beeby, who is a spectroscopist, and I said, this is super-weird,’ says Mahon.

Some online sleuthing showed this wasn’t a one-off occurrence, and Mahon found users of the internet forum Mumsnet seething over similar scarlet stains. The anecdotal evidence pointed to sunscreen reacting with household bleach, but she needed to narrow down the chemical culprit.

‘We bought a load of sunscreens, and we started doing a bleach test with them,’ she says. ‘The students just got really into this because it was a really interesting challenge for them to try and work out what was going on.’

Mahon and her team at Durham University, UK, tested 11 commercial sunscreens. Seven of them turned red, all of which had a common ingredient called diethylaminohydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate (DHHB). Of the four sunscreens that didn’t redden, only one contained DHHB.

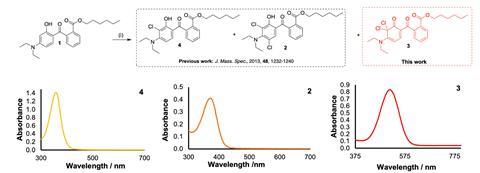

DHHB is an organic ultraviolet (UV) filter; it absorbs harmful solar rays and shields the skin. Organic sunscreens have gained in popularity over older mineral-based products, which can spoil the wearer’s beach-cred with a crusty white cast. However, some organic molecules are prone to chlorination, as indeed a study had identified for DHHB in 2013.2

This prior study had found that one of the aromatic rings present in DHHB underwent double substitution by chlorine, such that the substituents took different positions on the ring, meta to each other. But the resulting molecule’s absorbance profile lies mostly in the UV range, meaning no strong colouration. Mahon and coworkers suspected it wasn’t the only compound being made by chlorination, a hunch soon confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments.

‘We realised immediately when we saw the proton NMR that it wasn’t the meta-dichloro compound, because we had lost aromaticity,’ Mahon says. ‘[That] was the point when we got our computational colleagues involved to try and help us work out what it might be.’

Bringing their expertise together, the team uncovered an unusual ipso-dichlorination of DHHB, in which the two chlorines occupy the same position on the ring. Simulations predicted strong absorption of short- and mid-wavelength visible light, leaving only long wavelengths to give the vivid red hue they were looking for. Mahon notes that the meta- and ipso-dichlorinated forms can’t be distinguished by mass spectrometry, which might be why the latter hadn’t been picked up before.

It seemed they’d found their culprit, but to bolster their case and prove their mechanism, the researchers tweaked DHHB to make it resistant to ipso-dichlorination. Crucially, noting that the reaction required the generation of a ketone, they replaced the hydroxyl group on the aromatic ring with an ethoxy group. The resulting DHHB mutant was indeed resistant, and its UV absorbance profile barely changed from the original, raising the intriguing possibility that it could find use as a stain-proof UV filter. However, much more work would be needed to determine its suitability and safety in a sunscreen.

Vasilios Stavros, who researches sunscreen photochemistry at the University of Birmingham, UK, is likewise surprised by the study. ‘From my experience with the work that I’ve done on UV filters, this is one of the very few examples that I’ve heard of that react with bleach and cause a red stain… The more you look into these filters, the more you realise there are side-effects.’

The good news is that the ipso form is only metastable and will transition to the meta form over time, taking the alarming red stains with it. Mahon suggests using what Mumsnet contributors call “the sunshine trick” to hasten the fading. Happily, she reports that her own T-shirt has recovered, though she hasn’t worn it since: ‘It came into the lab with me and eventually became “Specimen A”.’

References

1 L G Smith et al, Chem. Commun., 2025, 61, 9314 (DOI: 10.1039/d5cc01593f)

2 G Grbović et al, J. Mass Spec., 2013, 48, 1232 (DOI: 10.1002/jms.3286)

No comments yet