Integrity, not just innovation

To some, there’s little better at this time of year than a smooth pint of bitter by the fire after a bracing winter walk. If you like beer, and even if you don’t, our feature is a fascinating insight into the chemistry of brewing and flavour compounds.

Brewing, along with fermenting, bread baking and cheese-making, is one of the original biotechnologies. Mention modern biotechnology, however, and gene technology is what springs to mind. Within just a few decades, this field has ramped up exponentially.

Analysing nucleotide variations is helping scientists to assemble gene maps of diseases for clinical diagnostics. But the recent push for precision medicine needs to be just that: precise. And for these techniques to benefit patients with conditions resulting from a single nucleotide change, maximum accuracy is crucial. We recently covered a new DNA sequencing method that ups the accuracy of a regular fluorogenic sequencing machine from 98 to 100% for sequences up to 200 base pairs long.

Also in this issue, we report how scientists have now expanded gene editing technique Crispr from DNA to RNA. This step is exciting because it could make it possible for medical personnel to treat diseases without permanently affecting a patient’s genome, eliminating concerns over genetic changes persisting in the germline.

A recent Crispr story in the news that didn’t grace the pages of Chemistry World was that of US biochemist Josiah Zayner who, during a live-stream, injected himself with DNA that could promote muscle growth. There’s a long history of scientists experimenting on themselves but Zayner’s stunt makes me uncomfortable because he used it to encourage the public to take a DIY approach to genetic engineering. And it just so happens he’s behind a company that can help you Crispr yourself.

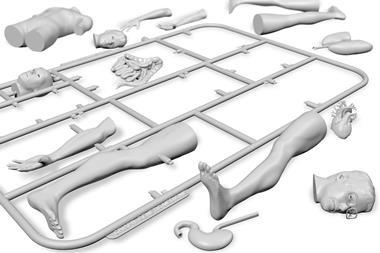

It therefore seems an appropriate time for a reminder that 1 January 2018 marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Many of Shelley’s readers felt this was a cautionary tale of scientists tinkering with nature.

Tools like Crispr may fix one thing, but we still don’t know if something else will break during the process. As one of Crispr’s creators Jennifer Doudna wrote in A crack in creation, the promise that gene editing offers is too great to ignore. That means having an open dialogue so the science has public support, before we consider human trials. Stunts like Zayner’s could ruin it for everyone else.

No comments yet