The war on sweetness will cost us a potent food ally

When food scientists began yanking the fat out of everything two decades ago, they were tasked with reformulating recipes to mimic its most famous character trait: creaminess. They succeeded – for the most part – with carbohydrate gums and pulverised protein. Yet fat isn’t a single purpose tool. It plays several functional roles in the kitchen, from providing a safe haven for hydrophobic pigments and aroma compounds to evenly distributing heat during frying. We may have gotten low-fat cream cheese that was creamy, but it had all the aromatic bouquet of cheap patio furniture. Since we’re now frenetically working to build a world without sugar, let’s pause to consider what we’re really losing.

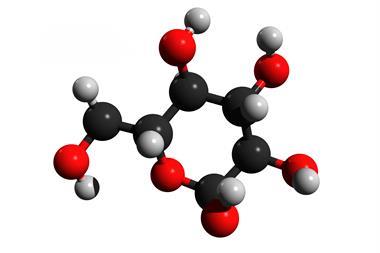

Sweetness, as simple as it seems, isn’t a binary concept – it exists on a spectrum. To our tongues, lactose is a faint whisper with so little sweetness per gram that we often overlook the high sugar content of skimmed milk. Fructose, on the other hand, gives us a raucous buzz, lighting up our taste buds with nearly an order of magnitude more potency per gram than lactose. Sucralose, an artificial sweetener with three hydroxyl groups swapped for chlorines, represents weapons-grade sweetness, generating taste stimuli several hundred times sweeter than sucrose. Sucralose is super-potent and non-metabolisable (thus calorie-free), which may seem like a miracle solution to our sugar-free conundrum. But sweetness doesn’t work as a simple function of intensity. In addition to ‘sweet’, our taste buds pay close intention to the character and duration of sweetness stimuli, which is why the search continues for a sweetener that matches the ebb and flow of a dose of natural sugar without a metallic, sour or bitter aftertaste.

Perserve and protect

Sugars are also highly hygroscopic, and their ability to absorb moisture and keep water where we want it is a foundational pillar of several cooking techniques. By leveraging water’s chemical fascination with the hydrophilic hydroxide groups on mono- and disaccharides, we help biscuits stay moist, cakes stay tender and roasted meat stay juicy. Taken to the extreme, this chemical quirk helps us discourage microbial spoilage by lowering water activity, preserving preserves and curing fish.

In addition to chemically binding water, sugars help us corral water physically. When added in large quantities, multitudes of sugar molecules make travel cumbersome for water as it flows back and forth, increasing viscosity. Sugar helps sauces become luxurious and sticky, slows the weeping of meringues, and sticks crispy clusters of granola together.

The disintegration of sugars into innumerable delicious pieces also gives us an explosion of flavour during Maillard browning and caramelisation. The breakdown of sugars with and without the aid of amino acids represents perhaps the most delicious form of decay known to mankind. Even though artificial sweeteners are slow to break down (and lack the reducing groups required for Maillard browning), the sugar-averse can still enjoy the benefits of these reactions because they require relatively small quantities to unlock the heady aromas and potent colours of browning reactions.

The ‘war on sugar’ will likely shine a spotlight on sweetness, completely missing the contributions that sugars make to sticky, golden brown, aromatic, tender, and preservative-free food. I have a hard time thinking of a good meal without at least one of those attributes, so maybe we should all just skip to the part where we realise that sugar in moderation is fine, and move on to whatever the next demon of the month might be.

Recipe book: Preserved lemons

Here is an excellent example of sugar’s ability to do various jobs at once. Sugar, in concert with salt, inhibits microbial spoilage, allowing these lemons to age and transform into a complex burst of citrus steeped in a salty-sweet, viscous lemon syrup. Add these preserved lemons to everything from crepes and yogurt to salad dressings and braised meat.

Ingredients

- 1kg lemons

- 160g salt

- 80g sugar

- 10g spices (optional)

Instructions

1) Cut the lemons in to quarters, leaving one end intact so the wedges remain attached to each other

2) Mix the salt and sugar together

3) Toss the lemons with the salt and sugar mixture

4) Toast whole spices (like cloves, cardamom, coriander or cumin seeds) in a dry pan until fragrant, then add to the lemons (optional)

5) Pack lemons tightly into a bowl or jar, cover and let sit for 15–20 days. Refrigerated, these will keep for a year or more.

1 Reader's comment