Ben Valsler

Whether you have a sweet tooth or are sweet enough already, sugars make up a significant part of our diets. Here’s Brian Clegg on a sugar so sweet, they named it twice…

Brian Clegg

There was a time when the dietary scourge of the healthy eater was saturated fat. Now butter is beneficial once more, while the ultimate nutritional nasty is sugar. All sugars are soluble carbohydrate molecules that give food an appetising sweet taste. All of them are bad for us. But the biggest villain of the piece in Europe, where it’s the most common form of added sugar, is sucrose. It’s so sugary, they named it twice – as the ‘ose’ ending denotes a sugar, while the ‘sucr’ part comes from the French for… you guessed it.

This same doubling is going on when we look at the structure of sucrose. With a makeup of C12H22O11 it’s known as a disaccharide, because it contains a pair of simpler monosaccharide sugars – fructose and glucose. When we consume sucrose it’s broken down by the acid in the stomach, aided by an enzyme called sucrase, into these two basic sugars. Sugars are very common compounds in nature because plants use them to store away the energy they generate from photosynthesis. Although in many plants fructose is the dominant sugar, it’s hard to find a plant that doesn’t have some sucrose present – and it turns up in the highest concentrations in the two main sources of table sugar. In temperate regions, the locally grown source is sugar beet, a variant of beetroot or Beta vulgaris resembling a yellow turnip, while in warmer climates it tends to be sugar cane, typically Saccharum officinarum, a thick bamboo-like grass.

The familiar white granulated sugar is extracted from either or both of these plants, purified and crystallised. For marketing purposes, whether the source is beet or cane is often emphasised, but it is practically impossible to distinguish the two, apart from checking variants of the carbon isotopes in the molecules.

Sucrose, in the form of sugar cane extract, has proved a desirable additive to the human diet for thousands of years, satisfying our natural urge to seek out the energy-indicating sweetness. Sucrose was first extracted and provided in crystalline form in India around two thousand years ago and spread as an exotic import for much of the rest of the world until the 1500s when sugar plantations began to make the product more easily available. Even so, it remained a relatively expensive import in Europe all the way up to the nineteenth century, when sugar beet was developed as an alternative. The impetus to make beet sugar popular was the Napoleonic wars, when the French, unable to obtain Caribbean imports because of a British blockade, were forced to find a native alternative.

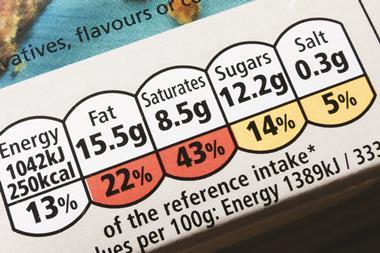

There is one reason only that sugar became such a massive industry and trade: we love the taste. But in dietary terms, sucrose does us few favours. Its only food value is as a carbohydrate. We have long been aware of one issue with sugar, which is that bacteria in the mouth convert sugars into acids that attack the teeth, causing decay. But this hasn’t stopped it being a major part of our diets, from the obvious sources of sugary drinks and sweets, to the more concealed presence in processed foods from bread to ready meals.

It is only relatively recently that we have become aware of just how many health problems can be caused by excessive sugars in a diet. Although sucrose itself does not significantly impact blood sugar levels, the glucose it produces when broken down does. This increases the chances of obesity and a whole range of risk levels for diseases including heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Meanwhile, the fructose from the sucrose breakdown contributes to fat build up. Sugar consumption is now recognised as a greater predictor of a tendency to obesity than fat consumption.

We tend to think of sucrose as the evil sugar, but it’s worth remembering that it’s sucrose that bees primarily convert into nectar, so not only does honey come from this source (though the bees have converted the sucrose to fructose and glucose by this point), but without sucrose we would not have those essential pollinators. Even so, most of us now recognise that we consume far too much sugar, and find ourselves battling the sweet tooth that tells us that sucrose is a compound we love.

Ben Valsler

Brian Clegg on our love/hate relationship with sucrose.

Next week, a compound at the heart of the 2005 bird flu scare and key to the controversy around glyphosate weedkillers.

Kat Arney

Composed solely of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, shikimic acid is an important starting ingredient in several multi-step biochemical manufacturing processes found in a wide range of lifeforms from bacteria and fungi to parasites and plants.

Ben Valsler

Kat Arney explains the importance of shikimic acid in next week’s chemistry in its element podcast. Until then, let us know if there are any compounds you would like to know more about, and you can find more chemistry stories on our website. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for listening.

No comments yet