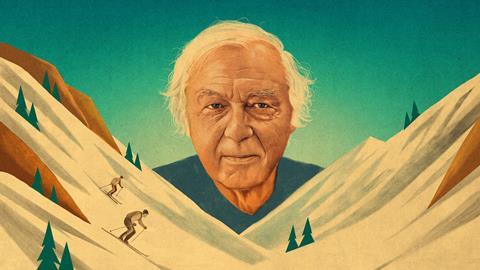

The Nobel laureate on the joys of entering a developing field, and the century of vision

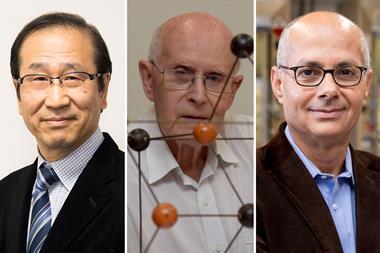

Robert Huber won the Nobel prize in chemistry in 1988, alongside Johann Deisenhofer and Hartmut Michel, for crystallising a protein important for photosynthesis in purple bacteria, and determining its three-dimensional structure using x-ray crystallography. He was speaking with Emma Pewsey at the 74th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting.

I’m a war child. There was no primary school, and when I entered high school, there was no chemistry. There was a little bit of biology.

I was interested in chemistry and asked my mother to buy chemistry books for me. I studied them, and was actually, I think, more knowledgeable than the biology teacher. I asked him questions or corrected him, and he did not like that – he asked me to stay away! That was my chemistry. Of course, I also did some of the usual explosive experiments.

It was quite natural that I studied chemistry at university. I lived in Munich, so I went to the Technical University in Munich, which was famous for its inorganic chemistry. Several Nobel laureates came from that university.

There was no biochemistry at that time in Munich, and I was interested in crystals. You see, Munich is close to the mountains. When you walk there, you find minerals and you find crystals – and I loved these, and I collected them.

I wanted to explore what molecules look like. And the only method that was available back in the 1960s was x-ray crystallography. So it was natural for my master’s work – it was called a diploma at that time – to be on crystallography.

When I was a PhD student, the biochemist Peter Karlson gave me some material of an insect hormone called ecdysone. That is a hormone that is responsible for the molting of insects. The chemists determined the composition, C, H, O, but not the molecular structure. This is where I came in. They asked me whether I would be interested in crystallising and determining the structure of this ecdysone. And I did.

I used a kind of x-ray crystallography very different from what is available today, simply because the methods and instruments were not developed at that time. I found out that ecdysone has a steroid structure related to the mammalian hormones of the cholesterine family. I published that together with my mentor, Walter Hoppe. Without his guidance, there would be no x-ray crystallographer Robert Huber.

What is life? Life is chemistry.

I had found my field of research, and got an offer for a professorship in Basel. I then got a counter-offer from Munich, which I accepted. The Basel offer was quite attractive at that time, but the Munich offer allowed me to stay where I was born. I love my hometown.

I was lucky to enter a developing field – everything you did was new. It was a great time. After I accepted the Munich offer, I started my group and went into protein x-ray crystallography – again, a field that had just been founded in Cambridge by Max Perutz. So I was lucky.

I call the last century the century of vision, because we learned to use light, electrons and x-rays to view molecules. Then came mass spectrometry – this is not an imaging method, but it is very powerful in defining the molecules. The science that gives us these new pictures has developed enormously in the last 20 years, so it’s a great time.

What I would like to confer to students is: have open eyes. Find out what your real interest is, then look for a laboratory or a person where you can develop what you wish further. Then approach that person, and if you’re lucky and if you’re good, you’ll get an offer for a master’s or a PhD project. That’s what I did.

I’ve been retired a long time. I still have an office in my institute that I joined in 1972. I helped in founding pharma companies and was successful in at least two cases. They all have their facilities in Munich, so I visit them frequently, two or three times per week, talk to people about what they’re doing and enjoy their success.

I like hill sports, that is skiing and bicycling – I even have a bicycle here in Lindau. I like classical music and would have liked to have learned an instrument, but I grew up in wartime. My four children all learned to play music – I have the privilege to listen and to enjoy them, but I can’t contribute to the performance.

It’s a great time in structural biology for medicine, understanding life. And what is life? Life is chemistry. A complicated chemistry, complicated molecules, but chemistry. In order to understand that life-chemistry, you have to see the molecules.

No comments yet