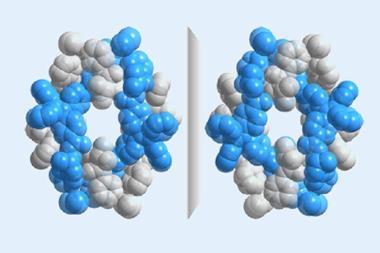

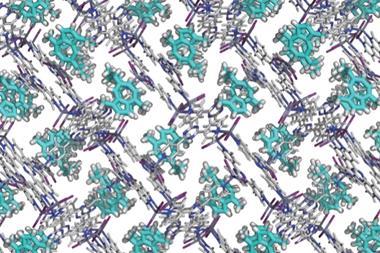

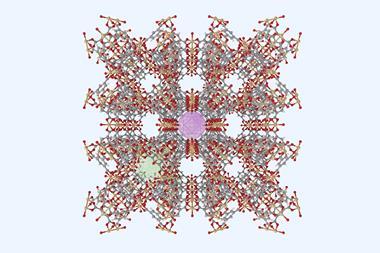

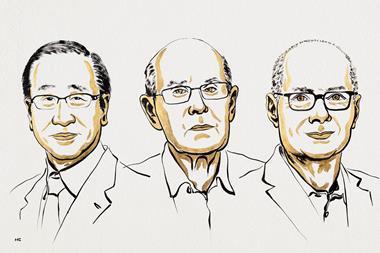

Three prominent chemists have just won this year’s chemistry Nobel prize for their work developing metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) – supramolecular constructions with large pores through which gases and other chemicals can diffuse and adsorb. We take a deeper dive into who they are and how they converged on the same innovative area of chemistry from different directions.

Omar Yaghi

Omar Yaghi from the University of California, Berkeley, who is often credited with founding the field of reticular chemistry that involves linking molecular building blocks through strong bonds to form open crystalline networks, is the youngest of the three winners at 60 years old.

He was born in Amman, Jordan to a refugee family that was originally from Palestine, with a dozen of them sharing one small room and the cattle they raised. ‘My parents barely could read or write,’ Yaghi stated in an 8 October interview with Adam Smith, chief scientific officer for Nobel Prize Outreach. Yaghi did the interview on the day he won the prize while in the middle of changing flights. ‘It’s been quite a journey and science allows you to do it, science is the greatest equalising force in the world,’ he said.

Yaghi’s love of chemistry was ignited in his third year of secondary school when he came upon drawings of molecules in his school’s library during a lunch break. He moved from Jordan to the US at the age of 15 but barely knew English. After finishing secondary school, he began studying at Hudson Valley Community College in Troy, New York before transferring to the State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany in 1983.

Once at SUNY, Yaghi was immediately drawn to research, taking on multiple projects simultaneously and paying his bills by bagging groceries and mopping floors. His dream at the time was to publish at least one paper that would receive 100 citations, and now he says his research group is estimated to have garnered over 250,000 citations.

Yaghi graduated from SUNY cum laude with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry in 1985 and followed this up with a PhD in chemistry from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign in 1990. He became an American citizen and was also granted Saudi citizenship in 2021.

Yaghi then pursued postdoctoral research at Harvard University from 1990 to 1992 and then taught at Arizona State University until 1998. Later, he joined the faculty of the University of Michigan and then the University of California, Los Angeles, before making UC Berkeley his home in 2012.

Beyond his research, Yaghi has worked to foster science internationally. He has founded several research centres in Vietnam, Korea, Japan, Jordan and Saudi Arabia, providing opportunities for young local researchers. ‘Smart and talented people exist everywhere in the world and that is why it is so important to focus on really unleashing their potential though providing them with opportunity,’ he stated during the interview with Smith.

Back in May 2019, he told Chemistry World that he doesn’t separate chemistry from his hobbies. ‘I’m in love with chemistry. Hobbies are something you do for enjoyment and relaxation – and for me that’s chemistry,’ he said.

Yaghi adds the Nobel prize to a long list of awards, which includes the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Centenary Award in 2010, World Cultural Council’s Albert Einstein World Award of Science in 2017, the Wolf Prize in Chemistry in 2018, the Gregory Aminoff Prize in 2019, the Tang Prize in 2024 and the Science for the Future Ernest Solvay Prize in 2024.

He is also an entrepreneur and founded Atoco – a start-up that aims to explore the commercial applications of MOFs and covalent organic frameworks to harvest water vapour from the atmosphere, among other things – in 2020. The next year, Yaghi co-founded another startup called H2MOF with the late chemistry Nobel laureate Fraser Stoddart to employ reticular chemistry in solid-state hydrogen storage.

Susumu Kitagawa

Susumu Kitagawa is a Japanese chemist who is a distinguished professor at Kyoto University’s Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences and also serves as Kyoto University’s executive vice-president for research and as deputy director-general of its Institute for Advanced Study. He pioneered the field of the chemistry of coordination space with his work on crystalline frameworks of porous coordination polymers.

Kitagawa’s work on metal–organic frameworks has had a significant impact in chemistry since his paper in 1997 that showed that coordination polymers could reversibly adsorb and release gas. He was also the first to predict the softness of MOFs and demonstrate their responsiveness to chemical and physical stimuli.

The 74-year-old was born in Kyoto and earned his bachelor’s and master’s in chemistry from Kyoto University in 1974 and 1976, respectively. Kitagawa went on to receive a PhD in hydrocarbon chemistry from Kyoto University in 1979. Later, he worked at the private Kindai University in Osaka and at Tokyo Metropolitan University, and he was appointed as a professor at his alma mater in 1998 and has remained there ever since.

While an undergraduate, Kitagawa worked in the lab of Teijiro Yonezawa and was a disciple of Kenichi Fukui, who in 1981 became Japan’s first chemistry laureate for his work on reaction rates. As a student, he took inspiration from the fourth century BC Chinese philosopher Zhuang Zhou and his notion of the ‘usefulness of the useless’.

‘Currently, most researchers focus on building so-called useful materials and publish many papers about them. However, the concept “the usefulness of useless” reminded me to explore some seemingly “useless” topics, for instance, porous structures,’ Kitagawa explained in an interview with ACS Materials Letters six years ago.

Kitagawa has spent his whole career in Japan, other than one year between 1986 and 1987 when he was a visiting scientist at Texas A&M University in the US. Among his most significant achievements is developing three generations of MOFs with increasingly complex structures and useful properties.

Last year, Clarivate Analytics designated Kitagawa a ‘highly cited researcher’, which means his work was in the top 1% by citations for his field. This marked the 11th year he made that list.

During a live-streamed Nobel news conference after the award’s announcement, Kitagawa said he was deeply honoured and delighted to win. He added that he really enjoys the chemistry of MOFs and the surprising properties of these materials. ‘My dream is to capture air and separate air – for instance, CO2 or oxygen or water – and convert this to useful materials using renewable energy,’ Kitagawa stated.

Asked whether he ever doubted that he would create such useful porous frameworks, he said he always remained optimistic because it is very challenging to create new materials. ‘I always told my students that challenges are very important in chemistry and in science,’ Kitagawa recalled.

Beyond the Nobel, his numerous honours include the 58th Fujihara Award in 2017 from the Fujihara Foundation of Science in Japan for significant contributions to scientific and technological advancement. Later that same year Kitagawa also received the Chemistry for the Future Solvay Prize for his work developing MOFs. In addition, he won the Humboldt Research Prize in 2008 and the Chemical Society of Japan Award shortly afterwards.

Kitagawa has said he chose chemistry as a career because ‘chemists understand the difference between ethanol and methanol’, and has indicated his favourite experiment is crystallisation of metal complexes because ‘it makes a start for our chemistry’.

Away from work, Kitagawa reads detective novels, enjoys kabuki and Super Kabuki theatre and watching European thrillers.

Richard Robson

University of Melbourne chemistry professor Richard Robson produced the first MOFs in the early 1990s and has continued to explore different forms of these materials ever since. Born in Glusburn, UK in 1937, he has been a lecturer and researcher at the university since 1966. His work has generated a new class of coordination polymers, and his models spawned an entirely novel field of chemistry.

After earning an undergraduate degree in chemistry from the University of Oxford in 1959 and a chemistry PhD from the same institution in 1962, Robson conducted postdoctoral research at Caltech in the US from 1962 to 1964, continuing on to Stanford University in 1964, before becoming a lecturer in chemistry at the University of Melbourne in 1966.

As a lecturer in the University of Melbourne’s inorganic chemistry department in 1974, Robson was invited by departmental head Don Stranks to build large wooden models of crystalline structures for first year chemistry lectures.

‘As I was constructing these models – putting metal rods of clearly defined dimensions into wooden balls with accurately drilled holes – the thought arose: what if we used molecules in place of the balls and chemical bonds in place of the rods? And everything followed from that,’ Robson recalled in a telephone interview with Smith right after learning that he won the chemistry Nobel on 8 October.

But Robson said not everyone was fully on board with this concept of building a new type of chemical construction while making models for teaching. ‘I must say that some people thought at the time – that’s in the mid-1980s – it was a whole load of rubbish,’ he recounted. ‘Anyhow, it didn’t pan out that way.’

Robson recalled not being ‘particularly thrilled by chemistry’ from the beginning of his days as a student, but said he ‘sort of drifted into it; I couldn’t think of anything better to do’. ‘I just mix things up and get compounds, the real science is numbers and angles and bond distances, and things like that; these are things I never would have achieved myself.’

His multiple awards over the years include being elected as a fellow of the Australian Academy of Science in 2000 and a fellow of the Royal Society in 2022, and having a professorial chair at the University of Melbourne named after him last year. Robson also received the Burrows Award from the inorganic division of the Royal Australian Chemical Institute in 1998 and is estimated to have published over 200 influential scientific articles.

The University of Melbourne’s deputy vice-chancellor for research, Mark Cassidy, described Robson as ‘a humble man who has achieved this honour by simply doing what he loves – going into the lab every day, talking with students, thinking big chemistry thoughts for decades and running experiments’.

Update: One of the past affiliations of Omar Yaghi was corrected to Arizona State University on 15 October 2025

No comments yet