Three-thousand-year-old treasures can still enthral and inspire

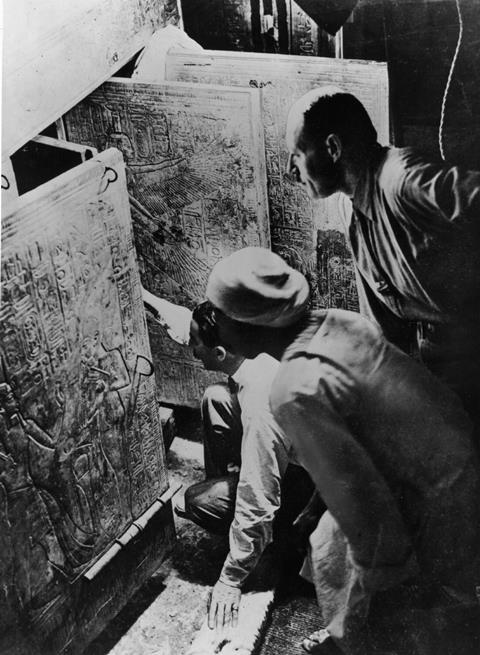

When archaeologist Howard Carter first broke through into Tutankhamun’s tomb 100 years ago, his sponsor Lord Carnarvon asked whether he could see anything. As his eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, lit only by the candle he was holding, Carter could see ‘strange animals, statues and gold – everywhere the glint of gold’. He replied ‘Yes, wonderful things.’

This sensational find, probably the most famous in all archaeological history, ignited a media frenzy, a global craze for all things Egyptian and fuelled Egyptian desire for independence from British rule. Amid the wider cultural significance and the wonderful story of the discovery, it’s easy to overlook that all the wonderful treasures found in the tomb, and the well-preserved body of the boy king himself, were made by skilled craftspeople around 3500 years ago.

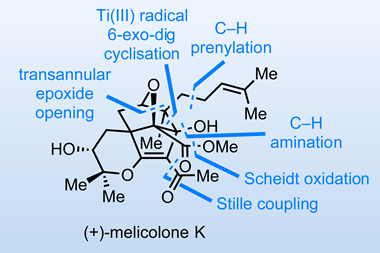

The skills of those ancient craftspeople of course included chemistry. As Rachel Brazil outlines in her feature on p24, the ancient people of Egypt were capable to some pretty sophisticated chemistry. They were the first civilisation to make their own synthetic inorganic pigment (Egyptian blue), and could even tune its colour by controlling the temperature at which it was made.

The skills of those ancient craftspeople of course included chemistry. As Rachel Brazil outlines in her feature, the ancient people of Egypt were capable to some pretty sophisticated chemistry. They were the first civilisation to make their own synthetic inorganic pigment (Egyptian blue), and could even tune its colour by controlling the temperature at which it was made.

The wonderful things with their glint of gold show what skilled metalworkers they were, but behind the gold mask was something that showcased their chemical prowess: the mummy. If there’s one thing that marks out ancient Egypt culture as different to our own, it’s their attitude to death, and the enormous efforts that were put into preparing the deceased for their journey to the afterlife.

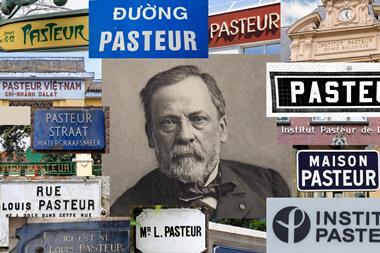

While the ancient Egyptians were experts at preserving the dead, Louis Pasteur was more concerned with preserving those still alive. To celebrate 200 years since his birth (just the blink of an eye compared to Tutankhamun), our feature on p48 looks at some of his achievements.

While the ancient Egyptians were experts at preserving the dead, Louis Pasteur was more concerned with preserving those still alive. To celebrate 200 years since his birth (just the blink of an eye compared to Tutankhamun), our feature looks at some of his achievements.

And what incredible achievements they are – it’s no wonder his name is remembered on everything from asteroids and Martian craters to universities, hospitals and thousands of streets around the world. From discovering optical isomerism to developing vaccines and putting germ theory on a firm footing, it’s amazing how wide-ranging his work was.

As Mike Sutton reflects in the article, not many scientists’ names live on in everyday use, but thanks to pasteurisation at the very least, Pasteur’s fame will continue to live on even longer. Whether it lasts as long as Tutankhamun’s, however, is something none of us will be around to discover.

No comments yet