Ben Valsler

This week, how a sports supplement lead to tragedy. Here's Enna Guadalupe...

Enna Guadalupe

Sunday 22 April 2012. The London Marathon. Claire Squires was one mile from the finish line when she started to stumble. A few seconds later, she collapsed to the floor. Paramedics and doctors raced to her aid in an attempt to revive her. But Claire, a healthy and fit 30 year old woman, was pronounced dead in hospital just an hour later. Her cause of death? Total heart failure.

A few days later, a coroner ruled ‘Methylhexanamine’ as a factor in Claire’s death.

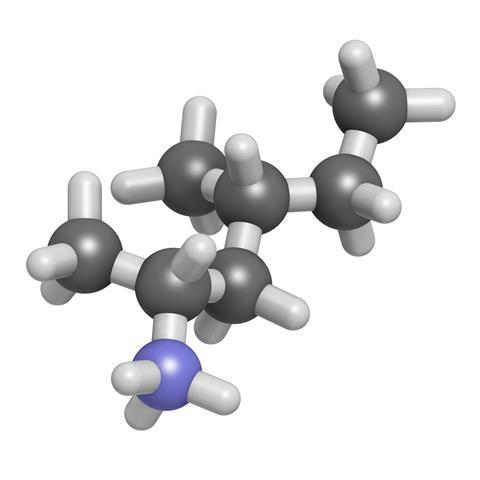

Claire’s partner, Simon Van Herrewege, revealed in an interview that she had purchased the pre-workout powder Jack3d online days before her race. After hearing the buzz about it at her local gym, Claire thought it could give her a boost during the marathon. Little did she know however, that this innocent looking powder contained the potent stimulant methylhexanamine, which is on the World Anti-Doping Agency’s list of prohibited substances. It’s also known as 1,3-dimethylamylamine or DMAA (which is what we’ll call it from now on, as it’s easier to say than methylhexanamine). It is a stimulant marketed as a dietary supplement; boasting claims of increased endurance, strength and extreme focus. It works by mimicking the effects of neurotransmitter noradrenaline, which increases heart rate, breathing rate and can cause vasoconstriction, leading to high blood pressure. When coupled with strenuous exercise, this can cause intense stress on the human body, resulting in the heart ‘giving way’.

In a recent commentary published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, Dr Pieter Cohen, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and general internist at Cambridge Health Alliance outlines the dangers of this ingredient by stating: ‘in people’s bodies, DMAA acts like adrenaline, which is normally produced in times of stress.’

The history of DMAA dates back a lot further than its use as a supplement. It was first released as a nasal decongestant under the name ‘forthane’ in the 1940s by pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly & Co, but was taken off the shelves in the 1970s for unspecified reasons. In 2006, once its trademark expired, it was reintroduced as a dietary supplement for weight loss and increased energy under the name ‘Geranamine’ by Patrick Arnold, a chemist known for producing designer steroids who was jailed for his involvement in a doping scandal. The new name was based on its alleged presence in Geranium extracts, which was later found to be false – scientists discovered that Geraniums have no DMAA in them at all. Thus, all DMAA in supplements and pills would appear to be synthetic, violating the all-natural ingredients rule behind dietary supplements.

The dangers of DMAA were shown not only in Claire’s unfortunate demise, but also that of two US army soldiers who tragically died during training after ingesting dietary supplements. The US army subsequently prohibited the sale of supplements that contained DMAA from their bases. These tragic stories, amongst others, highlight the urgent need to bridge the gaps in product safety and regulatory oversight of the $30 billion dietary supplement industry. Unlike medicinal drugs, supplements do not have to be proven effective, or even safe, before hitting the market. The United States’ Food and Drug Administration relies on reports from hospitals and doctors about any side effects of a supplement, before they decide to pursue an investigation. As a result of this, thousands of people are sent to the emergency room each year – some make it out alive, but others are not so lucky.

In recent years, DMAA has also made its way into the party-pills scene in New Zealand, being used as a replacement for the banned designer drug benzylpiperazine (BZP) or ‘smileys’. 3 cases of DMAA-party use in 2010, resulted in the individuals suffering from headaches, vomiting, irregular heartbeat and expressive dysphasia. Out of these 3 cases, one also suffered from a cerebral haemorrhage after mixing the compound with caffeine and alcohol. Though they all made full recoveries in the end - these incidents exhibit the harsh consequences of taking DMAA, especially in combination with other stimulants such as caffeine.

In early 2019 USPlabs, the maker of Jack3D and OxyELITE pro – another infamous and deadly supplement containing DMAA - ceased operations after years of battling with the FDA. But, several of their supplements such as the original Jack3d still remain widely available online, so fitness fanatics should be cautious of the supplements they are purchasing. Perhaps it’s time to stop wasting our money (and risking our health) on artificial means, and instead pursue the traditional combination of a balanced diet and regular exercise.

Ben Valsler

That was Enna Guadalupe with DMAA. Next time, join Georgia Mills to investigate a popular method of pest control in New Zealand.

Georgia Mills

Despite looking inoffensive - a pale white or colourless fluffy powder - and having no detecable odour, sodium fluoroacetate can be deadly to most animals, making it a popular poison.

Also known by the name 1080, it is used in many countries as a method for killing pests and invasive species.

Ben Valsler

Georgia examines the 1080 controversy next week. Until then, drop us a line with any compound suggestions – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. Thanks for joining me, I’m Ben Valsler.

No comments yet