Ben Valsler

A ‘pink pill’ to boost female sexual desire may have sounded too good to be true; and it turns out that may have been the case. Martha Henriques looks into why the drug seems to have flopped.

Martha Henriques

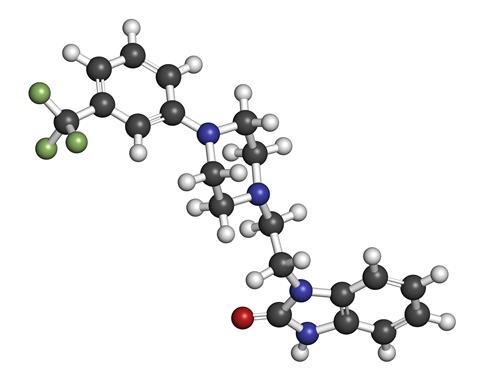

Flibanserin, a drug to treat female hypoactive sexual desire disorder or low sex drive in women, started life as a failed antidepressant in the 1990s. While it didn’t do much for mood, it did seem to increase female sexual desire and the frequency of satisfying sexual encounters.

To establish whether this effect was a freak of statistics or a genuine, reproducible effect of the drug, many more trials were needed to figure out the effect of flibanserin on women’s sex drive. They hoped that the failed antidepressant could be repurposed and sold to treat low sex drive in women.

In August 2015, flibanserin was approved by the US’s Food and Drug Administration. The company that took it through the last hurdles of the approval process, Sprout Pharmaceuticals, sold almost immediately afterwards for $1 billion.

But how does flibanserin work? The ‘pink pill’ is not a female equivalent to Pfizer’s Viagra, which treats erectile dysfunction in men by increasing blood flow to the penis. Instead – as you might guess from its start in life as a possible antidepressant – flibanserin’s effects are neurological. Exactly how it works is not yet clear; Sprout couldn’t characterise its mechanism exactly, and it’s unlikely that Valeant, the new owners of flibanserin, know much more just yet.

It is however clear that flibanserin is not Viagra for women. While a man with erectile dysfunction might have no problem with desire to have sex, physiology might foil his attempt. Flibanserin, on the other hand, isn’t for women who want to have sex but can’t. Instead, it’s intended for women who want to want to have sex, but don’t.

Jackie Thielen, a doctor working in sexual health the Mayo Clinic in Rochester in the US, told me that although the idea of flibanserin as a version of Viagra for women is too simple, the idea behind the drug isn’t all bad. Women’s sexuality and sexual health, she says, has been side-lined for too long. She says that interest from the pharmaceutical industry in making more options available to women is a step in the right direction.

But Sidney Wolfe, of the Public Citizen campaign group based in the US, opposed FDA approval of flibanserin earlier this year. He says there are too many questions over both the drug’s efficacy and its safety.

One of the main drawbacks of the drug, he points out, is that it can’t be taken with alcohol. This isn’t just precautionary. One of the common side effects that study participants reported when taking the drug with alcohol was rather unwelcome, especially considering the drug’s intended purpose: they got very sleepy.

Sprout’s answer to this was for doctors to ensure that patients are aware that they cannot drink alcohol if they want to use flibanserin. As alcohol is perhaps the most common aphrodisiac, this leaves women interested in the drug with an awkward choice: the pink pill or a glass of wine?

The alcohol dilemma is made worse by the fact that, unlike Viagra, flibanserin isn’t an on-the-spot fix. It has to be taken every day. So a woman who has decided she wants to try flibanserin has to give up booze for as long as she wants to take the drug.

Studies on flibanserin to assess the side effects of sleepiness leave several questions unanswered. Most study participants – 23 of 25 in one study – were men. Why test a drug for female sex drive on men? Apparently Sprout found it difficult to recruit women who were willing to consume the amount of alcohol in the study in a short period of time. So the effects of flibanserin combined with alcohol are mostly based on male physiology, even though men won’t be taking the drug. The effects on women could be much worse or better, but there isn’t the data to show for it.

Wolfe’s second main objection to FDA approval of flibanserin was that its efficacy is questionably low. He says that although study results are statistically significant, the effects are too marginal to be worth risking the common side effects of the drug.

But Thielen argues that while the effects of flibanserin might be slight, most women she encounters aren’t expecting a magic bullet anyway. A little improvement in sexual desire might be enough for some women, she says, and so that’s no reason to give up the drug altogether.

However the question of combining flibanserin with alcohol is a big problem, Thielen says. Most women, she finds, just aren’t willing to give up alcohol for the foreseeable future. This is the reason that take up of the drug has been very low.

Across the US, prescriptions of flibanserin – which led to Sprout’s sale at $1bn – stand at little more than 200. Even though doctors such as Thielen at the Mayo Clinic welcome flibanserin in principle, her clinic, at least, hasn’t yet made a single prescription for it.

Ben Valsler

Science writer Martha Henriques on the first drug approved to treat low sex drive in women, and why it hasn’t been a runaway success.

Next week, how a global pandemic made us question our decisions…

Chris Chapman

Fortunately, swine flu turned out to be a relatively tame pandemic; although at its height around 110,000 people in the UK were infected each week, just 214 deaths were recorded. But although the infection had been mild in the majority of cases, the aftermath was brutal for open science and government decision-making.

Ben Valsler

Find out more with Chris Chapman in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. And get in touch with any thoughts, comments or compound suggestions – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet