Meera Senthilingam

This week, Michael Freemantle investigates a strange white powder…

Michael Freemantle

In the year 1800, British chemist Edward Howard reported how he had treated mercury with nitric acid and alcohol to make a white crystalline powder. The material exploded violently when hit by a hammer. In other words, it fulminated. The new ‘fulminating mercury,’ as he called it, possessed all the inflammable properties of gunpowder. He wrote:

‘I first attempted to make the mercurial powder fulminate by concussion; and for that purpose laid about a grain of it upon a cold anvil, and struck it with a hammer, likewise cold: it detonated slightly, not being, as I suppose, struck with a flat blow; for, upon using 3 or 4 grains, a very stunning disagreeable noise was produced, and the faces both of the hammer and the anvil were much indented.’

A grain is an old-fashioned unit for a very small amount of material. It is roughly equivalent to one fifteenth of a gram. Howard was a cautious chemist advising that ‘a half a grain or a grain, if quite dry, is as much as ought to be used on such an occasion.’

He proposed that his mercurial powder might be used as a percussion initiator for gunpowder but was unable to demonstrate its use for this purpose. In 1807, Scottish clergyman Alexander Forsyth patented a percussion cap filled with a powder containing mercury fulminate, as it became known, and other compounds. The powder ignited when struck by a hammer. Forsyth’s invention led to the demise of flintlock weapons. These employed a trigger to release a hammer that struck a flint. The hammer blow generated a spark that ignited the charge of gunpowder in the gun.

Unlike Howard, Henry Hennell, another British chemist, was not cautious when it came to using mercury fulminate. He was, in fact, quite reckless and paid the price with his life.

In 1842, he had been commissioned to make a bomb to be used by British troops in the first Anglo-Afghan war that was then being fought in Afghanistan. While working at the Apothecaries’ Hall in Blackfriars, London, he mixed six pounds of mercury fulminate with other materials in a china bowl. The mixture exploded blowing him to pieces. The inquest revealed how the upper part of his body was shattered and ‘the fragments cast to a distance.’ One person found an arm on the roof of the hall and another picked up a finger in a street more than a hundred yards away.

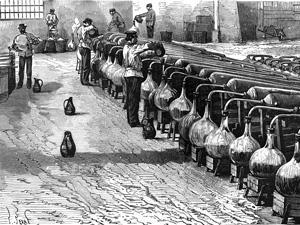

By the late 1860s, mercury fulminate was being widely used to detonate high explosives such as guncotton and nitroglycerine for both civilian and military purposes. The Swedish chemist and industrialist Alfred Nobel, introduced mercury fulminate for mining. He employed the fulminate by itself or in a mixture of with gunpowder in blasting caps to detonate dynamite, an explosive that contained nitroglycerine.

The powders in 19th century and early 20th century percussion caps used to fire guns typically contained mercury fulminate, antimony trisulfide, and potassium chlorate. Pulling the trigger of the gun released a firing pin that struck the cap causing the mercury fulminate to explode. The heat and flame of the explosion ignited the antimony trisulfide, a combustible compound. Potassium chlorate, an oxidising agent and also an explosive, supplied the oxygen needed for the combustion.

The production of percussion powders was a perilous activity. In his book on the chemistry of powder and explosives published in 1943, American organic chemist and explosives expert Tenny Davis noted that the powders were ‘usually mixed by hand on a glass-top table by a workman wearing rubber gloves and working alone in a small building remote from others.’

Fans of the American crime drama TV series Breaking Bad will be well aware of the dangers of the explosive. In episode six of the first series, Walter White, a chemistry teacher turned criminal, throws some crystals of mercury fulminate onto the floor during a meeting with a rival drug dealer. The resulting explosion blows out the windows of the building.

Mercury fulminate is not only extremely sensitive to shock, it also detonates spontaneously when subjected to friction, hit by a spark, or heated. So if you, like Walter White, are thinking of preparing or handling even a small amount of the material, one word of advice: DON’T.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Michael Freemantle, cautioning against the chemistry of mercury fulminate. Next week, have you got this compound?

Brian Clegg

There are some simple inorganic compounds guaranteed to be found around the home and none more so than manganese dioxide, which is almost certainly lurking in your house, quietly performing its function until you throw it away or recycle it without ever being aware of its presence.

Meera Senthilingam

Find out just where it lurks, as well as its uses, in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet